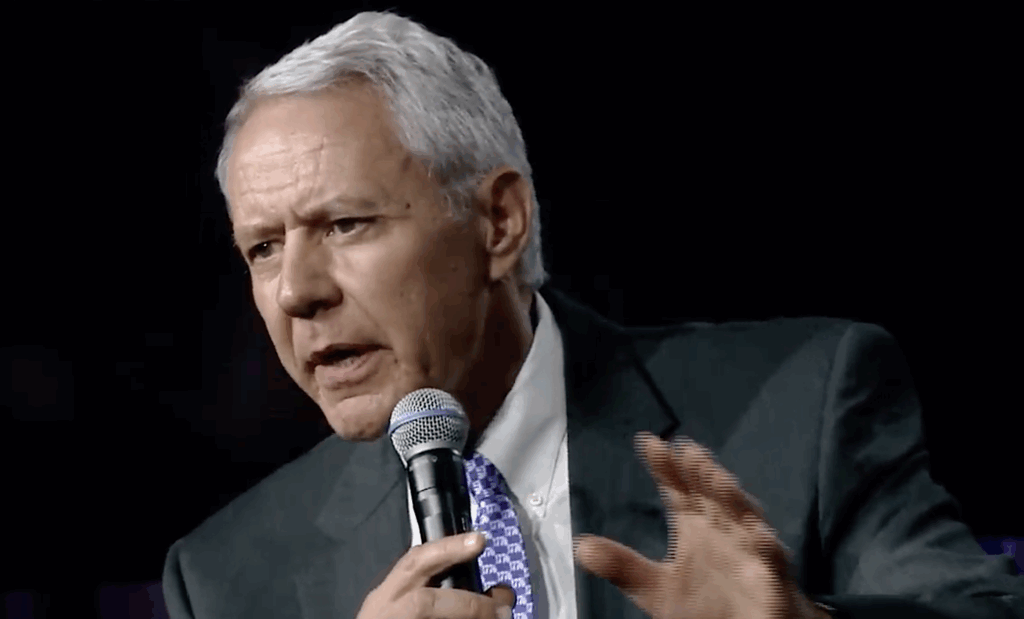

Q&A with Debra Johnson | ‘Public policy is my calling’

Denver Clerk and Recorder Debra Johnson – whose office oversees elections in Colorado’s largest city – will be winding down a lengthy career in public service next spring. She announced last year she will not seek a third term in her post in next spring’s municipal election, but as she looks at retirement, she seems to be keeping at least one eye on further involvement in civic life.

As she tells us in today’s Q&A, public service is deeply ingrained in her, so, “…don’t count me out completely; I’m keeping my options open for a passion project.”

Johnson, who has spent much of her productive life so far building a deep knowledge base on elections – from the policies that undergird them to the nuts-and-bolts mechanics that drive them – shares some of her insights below. Read and learn.

Colorado Politics: Clerks are far more than custodians of records and air-traffic controllers of our elections. They actually can have a lot of power over policy making. You have implemented assorted changes to Denver’s election system, some high-profile, some obscure but far-reaching. You even played a key role in ushering in same-sex marriage – in a roundabout way through the courts – by forcing a court challenge that ultimately led to legal recognition for such marriages.

What do you feel is the most important change that has been made to Denver’s elections during your two terms in office? What were some of the biggest changes to the state’s election and campaign regulations?

Debra Johnson: As we head into the November election and the municipal election next May, I’m reflecting on what legacy I will leave for Denver and for all of Colorado. I’m pretty darn proud of changes I’ve made in my two terms as Denver clerk and recorder.

In 2013, Denver was instrumental in bringing the mail ballot delivery method to the state through the legislative process. My office built support from both sides of the aisle to ensure that all Coloradans have equal, and easy, access to the polls. Even though we were strong advocates of the mail ballot method, we understand that many people still want to vote in person.

This legislation saved taxpayer money by allowing people to drop off their ballots or vote at any Voter Service and Polling Center. Expanding voter registration to allow people to register and vote on the same day is an enviable model around the nation.

You mentioned lawsuits; well, I was involved in a few lawsuits. The prohibition on sending ballots to inactive, failed-to-vote (IFTV) voters was overturned by Denver District Court. I fought to send ballots to IFTV voters because simply skipping an election shouldn’t mean voters have to jump through additional hoops to get a ballot. We’d been mailing ballots to IFTV previously.

But probably the most infamous law suit was around marriage equality. Denying same-sex couples the right to marry was one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever had to make. But I believed being sued was the only way to bring marriage equality to Colorado. Standing up for marriage equality put my personal life in the spotlight; it put my family in the spotlight.

My family encouraged me to take the risks, to stand up for what I truly believe, to be the voice for so many loving couples who felt they had no voice.

I hope that when people think of my public service, they view me as a champion for the people – whether it be for fair and free elections or for the right to love and live as you choose.

Debra Johnson

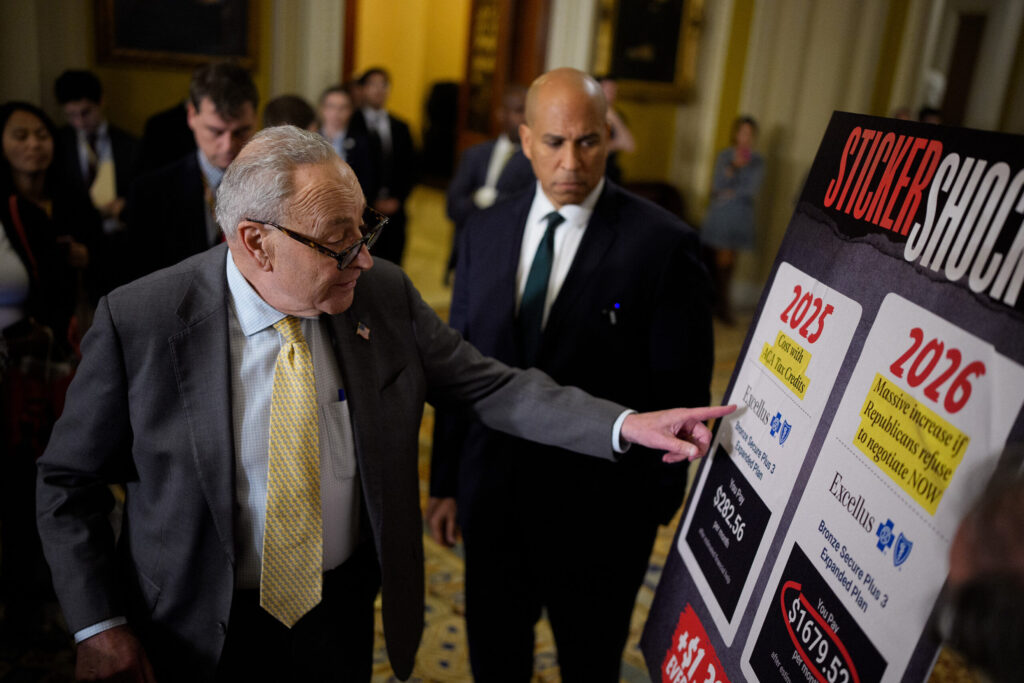

CP: A question on the Denver ballot poses groundbreaking changes to local campaign finance rules. One of its provisions opens the door to public funding for candidates who agree to certain limitations. Another provision lowers contribution limits for all local candidates.

You were intensively involved in negotiations between the proposal’s backers and the City Council, which ultimately agreed to place a version of the proposal on the ballot – a sign, perhaps, of the idea’s high likelihood of success on Election Day. Given your years of experience running municipal elections, what do you think will be the ultimate, long-run impact of the proposal?

Johnson: Campaign finance laws were a large focus of my office in 2017. We updated and revised the city’s campaign finance laws to make the process more transparent and add additional accountability of the candidates.

Because of the timing of the original petition, I was concerned about the implementation. I’m grateful for the work Council Member Kevin Flynn put in on the proposal that voters will now see on the ballot. If the initiative passes, we should be able to put the system in place by the revised deadlines.

CP: A credible case can be made that one unintended consequence of Colorado’s sweeping campaign-finance reforms and contribution limits adopted by voters in 2002 was that they actually wound up driving more political spending underground. Arguably, that money only re-emerged as “dark money” spent by third-party committees beyond the reach of regulations. Could Denver’s current campaign-reform proposal now facing voters make matters even worse in that regard?

Johnson: I hope that every voter will take the time to research the candidates and the questions on the ballot. We’re trying to help voters with that research with this year’s Blue Book. For the first time, all local questions will have a pro/con section in the Blue Book distributed by my Elections Division.

CP: You were Aurora’s clerk for years before being elected clerk in Denver in 2011. By the time you wrap up your current term – you announced last year you wouldn’t seek another – you will have spent a lengthy stretch of your productive life running and policing elections. What led you to that calling?

Johnson: I’d say public policy is my calling; I happened into elections when I moved to Colorado. Elections administration is like a cult. It gets into your psyche, and it is hard to get rid of. I love elections administration because of who we elect into office, and the laws established effect every part of our lives. I love the challenge of making sure every eligible voter has the opportunity to vote.

CP: What lured you to public policy in general, having also served a stint as policy director for the National League of Cities in Washington, D.C.?

Johnson: I realized the importance of public service shortly after I got out of college. I worked for the state of Michigan and then went into management in a large, private corporation. Very quickly I saw the difference in providing a public service to people versus serving the shareholders. I choose to serve the public. Municipalities are close to my heart, and even when working on legislation at the Capitol, I always ask, “What’s the effect on municipalities?”

CP: Have you ever considered running for Colorado secretary of state, overseeing elections statewide?

Johnson: I love serving at the local/county level. I can see the change more immediately and have a deep connection to my constituency. I like being innovative and seeing my innovations spread across the state.

CP: A touchstone among public policy advocates where elections are concerned is that, ideally, they should be competitive. Yet, most, in Denver as well as across the state, are not. Like various other Colorado climes, Denver is effectively a one-party town. In your experience, does that foment apathy? How in general do we make elections more competitive, engaging more of the public with more meaningful choices?

Johnson: I think this is changing. We have a municipal election slated for May 2019; there are only two seats open [with no incumbent]. But more than 40 candidates already have filed to run in May. I think that with all of Colorado being purple, that means that voters are looking to connect with a candidate who shares their ideas and their ideals. Voters aren’t looking for a straight party line because they don’t follow one themselves. You can check out the candidates who have declared for the May 2019 election on my website.

CP: If one more change in Denver’s election process could be made – whether by the clerk, the City Council or even the courts – what should it be?

Johnson: I’d like to see Denver adopt Rank Choice Voting. Currently, a candidate for a city office needs to win by more than 50 percent of the vote. In 2019, we’ll have a runoff 30 days after the municipal general election. That runoff will cost about $700,000. With Rank Choice Voting, the 50 percent majority would be accomplished in one election. I think that we’d also get higher participation because we wouldn’t run into summer vacation plans and voter fatigue. The voters would actually find out who won in May instead of waiting another month after another election.

CP: What’s next for you after you leave office?

Johnson: Right now I am looking forward to retirement. I recently bought an RV and am making plans to do a little traveling. But don’t count me out completely; I’m keeping my options open for a passion project. You probably haven’t heard the last of me fighting for civil rights and fair elections.