Beauprez: Shared principles can help GOP ‘right the ship’

In the weeks leading up to the November election – before Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump rallied in the polls, throwing what had looked like an easy win for Democrat Hillary Clinton up in the air and turning it into a historic Trump victory – there was nearly as much chatter about the impending civil war in the Republican Party as there was about the frantic scramble for votes.

Like so much this election cycle, the rift appeared poised to turn on Trump, whose candidacy exposed fractures in the GOP and split Colorado Republicans between those supporting the nominee and, in a nearly unprecedented development, top officials and candidates making clear he didn’t have their endorsement and some even saying they refused to vote for him.

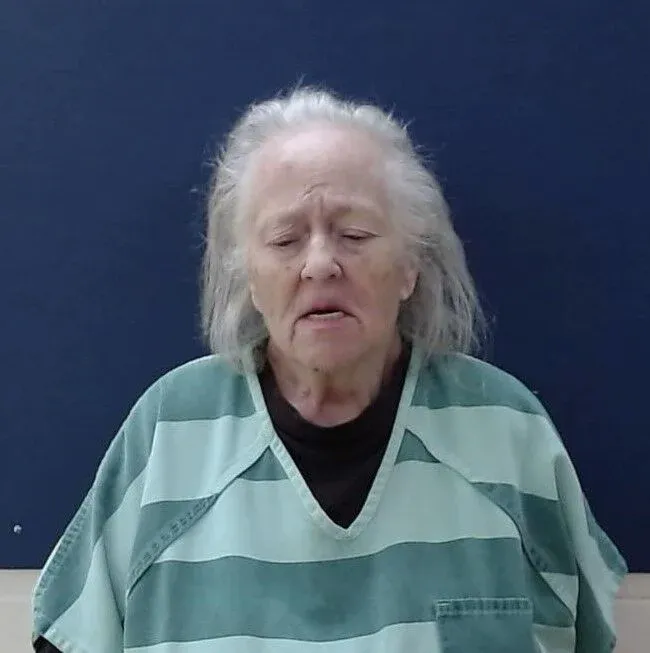

While Colorado polls tightened about a week before Election Day – Clinton’s double-digit lead earlier in October slimmed to just a few points, according to poll aggregators, and Republican Senate nominee Darryl Glenn looked for a while to have pulled within a few points of U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet by the same measures – former U.S. Rep. Bob Beauprez, one of the foremost figures at the center of state Republican circles for some two decades, was spending time thinking about where the GOP would land after the election and, win or lose, how to mend the fractured party.

“‘Where do we go from here?'” Beauprez posed in a recent interview with The Colorado Statesman, conducted before the election. “My gut churns” with the question, he added, but also noted that he’d been there before and was confident the party could rebuild.

“The party looks like it’s in a little bit of disarray right now, in various factions,” Beauprez said, noting that he’d taken up the challenge to help bring state Republicans together in earlier times, when Republicans were divided over issues or the party appeared to be shaken after a thumping at the ballot box.

“The ’06 election certainly wasn’t very good, and ’08 spelled more of the same,” he said, recalling that after Republicans had taken a bath at the polls in 2006 – Beauprez lost the first of two unsuccessful runs for governor that year by a wide margin – he’d written a book, “Return to Values: A Conservative Looks at His Party,” to make a case similar to the one he was preparing to argue in the wake of the 2016 election.

A move to re-embrace a shared purpose, he said, would get the GOP on course to come together.

“Conservative principles – beyond what we label today as conservative or liberal – I think the principles that have largely guided what has continued to be called the Republican Party, and Republicans in general, are traditional values and principles, and they’re not going to go anywhere,” Beauprez said. “The question becomes, ‘Where do people like that go?’ I’m obviously going to hope it’s still the Republican Party and that we can right the ship.”

While he stressed that he wasn’t predicting a poor performance by Republicans at the polls – “I know what the polls say, but we’ll wait until after Election Day to figure out where we’re at” – Beauprez pointed out that a loss could have a sobering effect and help focus Republicans, as it had in recent cycles.

“It can certainly be a rallying cry,” he said. “You certainly saw that with the election of Barack Obama. We didn’t take back the presidency in 2012, but so many state legislatures, so many governors, so many members of the House and Senate came on board, and built majorities as a result. They didn’t become Barack Obama – far from it, they ran on conservative principles, conservative pledges, conservative agendas. I think what will need to happen is, we’ll do a post-mortem, and regardless of whether we win or whether we don’t, we need to bring together people who agree 80 percent of the time.”

He acknowledged that the fractures in the party this year sprung from different causes than the ones that had left the GOP reeling a decade ago.

“Back in ’06 and ’08, specifically, there was some palpable Bush weariness, no doubt about that, and most of it was focused on the war, the old ‘Don’t fight at home, don’t fight alone, but for sure don’t fight very long,’ and the fighting very long had caught up,” Beauprez said. “That was an ideological test. This is not so much an ideological test. In fact, a great many of Trump’s strongest supporters have said, ‘I don’t care what’s on his agenda, I just want someone to go in and shake it up.’ Outsider – that became the issue.”

Beauprez supported Trump – “There’s reason to be optimistic that he’s going to surround himself with great people and do great things,” he said – but also said it’s clear that Republican primary voters weren’t embracing conservative principles when they picked their nominee.

“We had 17 people running for president at one point in time, and virtually all of them were making a case that they were the conservative who could be trusted – the old William F. Buckley test, ‘I’m for the conservative that’s most likely to win.’ We had a whole plethora of them, and then came Donald Trump,” he said.

“Donald didn’t have the greatest conservative bona fides that most of the rest of them had demonstrated for most of their life, hadn’t been in the political arena, hadn’t even been in Republican Party politics until very recently,” Beauprez observed. “But none of that seemed to matter, regardless of what he had said, what he had done, what he had contributed to, people were not looking for ideology, and they certainly did not appear to be looking for electability this time, because poll after poll way back then, and since, said that there were other candidates in the race that were more electable than Donald Trump. What they wanted was somebody that fit their outsider definition, and they got it.”

Beauprez said he believes Republicans were expressing their outrage, and Trump’s unconventional campaign was the beneficiary.

“Most of that, I think, was out of a great deal of largely justifiable frustration with the system,” he said. “They wanted to make sure that their voices were heard and that they poked the system – ‘The Man’ – that they poked it in the eye, and whether ‘The Man’ was represented by the RNC or by Republicans in office or any particular individual, this was their way to demonstrate their enormous frustration that ‘I’m mad as you-know-what, and I’m not going to take it anymore.'”

The reasons for the frustration, Beauprez added, were there for all to see, and addressing it would be part of any effort to reunite the GOP.

“Eight years later (after Obama’s election), you’ve still got 70 percent of the people saying we’re still on the wrong track. Someday, and I hope it’s soon, we’re going to need leadership that gets us back to feeling good again and feeling like we’re on the right track, making progress, but now is not the time, and Hillary Clinton is not the candidate to change that,” he said.

Beauprez rejected any suggestion that Republicans had sown the seeds of their own discord by obstructing government or, in a favorite phrase of centrists, refusing to work across the aisle.

“I don’t have any doubt in my mind that Darryl Glenn would have been a ‘no’ vote on Obamacare and a ‘no’ vote on the Iran deal,” he said. “Regardless of what Michael Bennet wants to say in his ads, or pretend that somehow he’s this ecumenical force out there, I hold him enormously responsible for those two votes, which I think are just absolutely wrong as wrong could be. So if that’s an example of trying to work across the aisle, I’m glad that Republicans didn’t en masse support Obamacare, which is an absolute disaster, or the Iran deal.”

The rank partisanship cuts both ways, Beauprez added.

“There is certainly a fair concern among many people that Democrats and Republicans don’t work well together, but this is absolutely not a one-way issue, though,” he said. “I was there, and shortly after 9/11, I was absolutely astounded how quickly that spirit of ‘we’re all in this together’ had already frayed and, shortly thereafter, greatly evaporated, largely under the leadership – and you can put that in quotes – of Nancy Pelosi. If you want to talk partisanship, that is very much evident on the other side as well, it’s not just, ‘Gee, I wish Republicans will reach across the aisle.’ If you reach across the aisle, you will be handed a scorpion in almost every case. That’s the environment that exists there.”

The answer, he said, wasn’t for his own party to start compromising with heavy-handed Democrats but to figure out how to present a more united front, at least in part.

“For Republicans, specifically, the thing that I would hope would happen is, first, they would decide they could work better among themselves,” Beauprez said.

He recalled that congressional Republicans had long sorted themselves into two camps, with members of the more ideologically pure Republican Study Committee – Beauprez was a member during his two terms in Congress – sometimes distinct from what he termed “the main street crowd,” who considered themselves more moderate, particularly on social issues. “But in case after case after case, the agenda we brought to the floor, the Republican caucus hung together on the key votes. That’s not the case anymore. You not only have two caucuses, you have three, including the (House) Freedom Caucus,” he said.

“My message to them would be, first and foremost, realize on the vast majority of major issues and the vast portion of major issues, you are going to agree,” Beauprez continued. “The real enemy in the room is typically not fellow Republicans, people that had made a conscious decision to identify themselves as more conservative than progressive. Your real political opponent is on the other side of the aisle. And until we hang together as conservatives – and we haven’t done that very well of late – it’s kind of cart before the horse to think about reaching across the aisle first. Better take care of your own house first, and that’s a house I’m concerned about.”

His own frustration was evident as the discussion turned to looming problems Beauprez charged neither presidential candidate appeared willing to confront.

“When you’re given a question in the debate about the $20 trillion in debt that we are facing, and both candidates – both candidates – just went right on by and never even talked about it or acknowledged it,” he said, his sentence trailing off as he shook his head. “When you’re given a question about entitlement reform – I was there, I know, no politician wants to touch that third rail, but unless we’re willing to touch that third rail, forget about my kids, my grandkids and the generations to come after us. That one and the debt are not rocket-science public policy, they’re arithmetic, and the numbers don’t work. It terrifies me that we’ve got politicians who pretend that’s just all magically going to work itself out.”

Beauprez ticked off a list of Democratic initiatives, including the Affordable Care Act and the Iran nuclear deal, he said were clearly going to lead to problems but passed without Republican support. “And yet it was done, and we’re supposed to be the big dummies,” he said, sounding angry. “We aren’t big dummies, and at some point we’re going to have to stand up, explain that and build big enough coalitions to get elected. I know that’s not easy to do now, but our Founders, my dad’s generation – World War II – they didn’t have it easier, but they cinched it up and they did it. Are we going to blink and not do our duty and not only save this republic but pass it on, as previous generations have done, better than we found it? If we’re going to pass it on better than we found it, we’ve got a long way to go to right the ship.”

The solution, Beauprez said, might lie in a technique that worked when he chaired the Boulder County Republican Party in the late 1990s and was state GOP chairman at the turn of the millennium.

“We had become a very divided party,” Beauprez recalled, adding that social issues often exposed the fault lines nearly two decades ago. “I had brought together representatives of both factions and said, ‘We’re going to try to talk this thing through.'” So he assigned representatives of both camps to committees and charged them with working out assembly resolutions that could get support from both sides, and that’s what happened.

“Nobody left screaming at each other and we proved that, by golly, as Ronald Reagan said, that we agree more than we disagree. At least for a while, we made some progress coming together,” he said. “How do you do that? You do it by the old-fashioned strategy of being respectful, of being gentlemen and gentle ladies, of respecting somebody else’s idea and recognizing at some point a majority has to lead. You get on board, wearing the team jersey, and you follow.”

“Right now we’ve gone through a period where people are so bloody frustrated that they’ve lost faith in the party and, in many cases, with each other,” he said. “We have to rebuilt that trust and confidence that, one, our principles work, and that, two, we not only can work together but we must work together, because we’re stronger, and it’s about the bigger picture of saving this republic.”

Beauprez paused and said he wasn’t sure what the formal procedure would be to bring back together the state’s Republicans, or whether he would even embark on a formal procedure – maybe some writing, maybe bring together groups of GOP stakeholders – but he said there was one thing he was sure about. “I know what I won’t be doing, and that is, I won’t be giving up on this state and this nation,” he said. “They mean too much to me.”