Energy Secretary Moniz celebrates climate research in Boulder

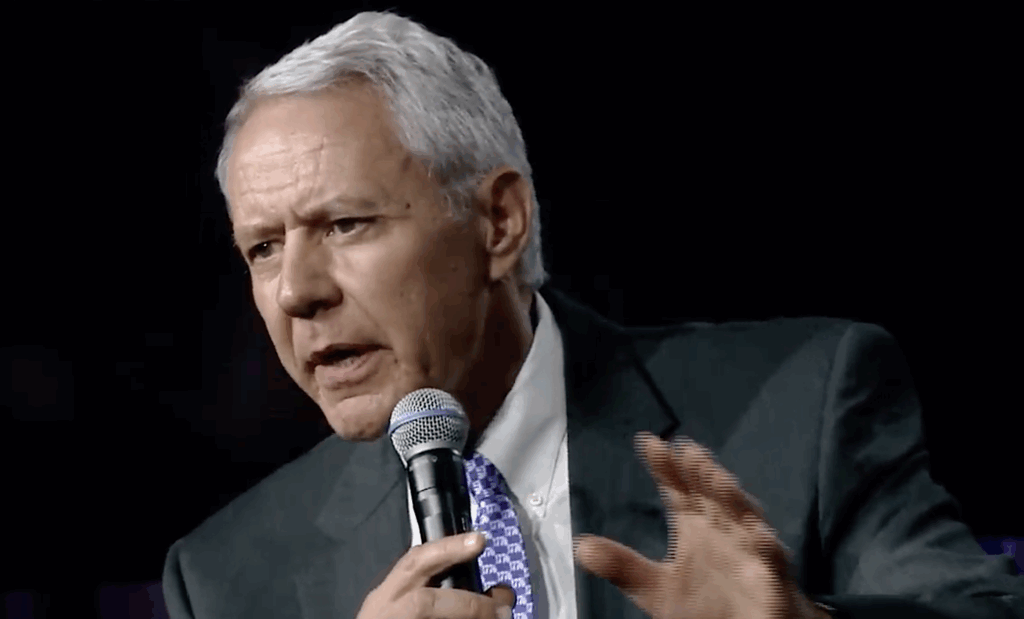

BOULDER — Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz toasted the work of Colorado researchers Monday in a swift one-hour roundtable on climate change with U.S. Rep. Jared Polis at the University of Colorado.

“We need more of this,” Moniz told the roughly 20 gathered in a law school conference room. He said the work presented at the gathering was the kind of work he was attempting to foster at the national level. The work had regional focus and was the product of deep cooperation across disciplines and professions. “We have been setting a different course with our labs. We want them to work as a system with greater emphasis on cooperation than on competition.”

Polis told The Colorado Statesman that, on that score, the lightning-fast discussion was a success. He said the point of the event was to “highlight the science being done in Colorado and the collaborative way it is being approached.”

CU Boulder was an obvious choice for the meeting, its flagship campus home to renowned environmental programs and institutes that draw researchers across disciplines who collaborate with nearby federal offices and labs.

Jeff Lukas with Western Water Assessment, a research program based at the CU, launched the discussion with an overview of the Colorado Climate Change Vulnerability Study, a study commissioned by the Colorado Energy Office that came out in February. It predicted how climate change is affecting and will affect the state.

A warmer Colorado will see air quality diminish and affect crops and livestock, he said. More residents will be afflicted by infectious diseases and respiratory and heart trouble. He also talked about decreased water flows and increased demand for water.

Moniz wanted to talk about water.

“Yes, this is something people understand,” he said. “Water scarcity and forest fires, people are familiar with these things. But they know less about how all of these things are connected.”

National researchers have grown increasingly interested in the relationship between energy use and water consumption. Moniz mentioned the “Sankey” diagrams that pop up everywhere in the research, making clear which energy sources gulp up water.

At one end of the spectrum is wind, which takes zero gallons of water to produce a megawatt-hour of energy (enough to power 1,000 homes for an hour). At the other end is coal and solar-thermal that uses the wet-cooling technique. Coal takes 687 gallons of water to generate a megawatt-hour, and solar thermal takes 786 gallons.

Lukas told Muniz that, indeed, the Colorado climate report talks about fires as well as pine beetles and other pests, all on the rise due to warming. He said it’s important to convey “what we all know… that our forests are our water towers.”

Polis noted that Colorado is a geographically diverse state and asked whether research suggests effects would be more pronounced in different areas.

Lukas said residents in all areas of the state will note changes, that resources will be at risk, that there will be greater dust storms, dwindling ranch water, dipping crop yields and shrinking ski seasons.

General comments followed about increased cooperation between environmental researchers and the oil-and-gas industry, particularly with regard to water management, and observations that the labs benefit from oil-and-gas funding.

Lukas noted that essential funding for the climate report came from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, also located in Boulder.

“Yes, well, we hope to keep that kind of funding in the [Department of Energy] 2016 budget,” said Moniz, turning to Polis, who was seated next to him. “We hope Rep. Polis will help realize that goal.”

Moniz asked what kind of traction climate research was getting outside of Colorado in the region and talked about the “central nature played by the states in bringing policy innovation.”

Lisa Dilling, a professor in Environmental Studies and a researcher at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, said there are challenges facing work on climate change in conservative states such as Utah and Wyoming, but hopeful signs, too.

“Fifteen years ago, we had no traction with Utah. Now they’re worried about water supply,” she said. “Wyoming is a different story,” she added. “In the water sector, people there are beginning to look at the work… But there’s a lot less traction generally.”The specter hanging over the discussion was the national tug-of-war over climate change.

Although the Obama administration has taken steps to encourage public acceptance of the science of climate change and to promote the renewable power industry, Congress controls long-term research funding and industry loan and subsidy policies, and it is controlled by Republican majorities determined to cut climate change research and renewable-energy support.

Polis told The Statesman after the event that Congress should be addressing the threat of climate change head-on and working proactively to address its challenges, but he added he has also found “broad support for [climate change] programs among members, so long as you don’t mention the term climate change. All of the states face environmental and resource challenges,” he said, adding that public officials have to do a better job underlining the increasingly positive effects climate change research will have on state economies and on job creation.

“But now we’re going into the tough months, instead, where we face a government shutdown as a way to target certain programs with policy riders.”

He scrunched his lips and shrugged.

CORRECTION: Lisa Dilling’s positions and affiliation were misidentified in an earlier version of this story. She is a professor in Environmental Studies and a researcher at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, a partnership between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and CU-Boulder. She directs the Western Water Assessment, part of CIRES.