Colorado River basin governors head to Washington, but lack of progress raises specter of litigation

Feb. 14: that’s the next deadline for the seven states of the Colorado River to come up with agreement on how to manage the river once the current operating guidelines expire.

The Bureau of Reclamation would like the next guidelines to be in place by Oct. 1, the beginning of the next water year, but an historic meeting in Washington last week didn’t produce an agreement, although a statement from the governors indicated optimism that an agreement is still possible.

Interior Secretary Doug Burghum, at the behest of Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs, summoned the seven governors and their river negotiators to Washington to discuss where the negotiations are heading.

Six of the seven governors attended; California Gov. Gavin Newsom had a prior family commitment. California Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot represented the state at the meeting.

Hobbs, in a December letter to Burghum, said her state has not waited for a crisis to act.

“We have paired growth with conservation, adding millions of residents while essentially keeping overall water use flat,” she wrote.

That hasn’t always been voluntary. In 2021, Arizona’s allocation of Colorado River water was cut by 512,000 acre-feet, about 18% of its 2.8 million-acre feet annual allocation. Nevada’s allocation of 300,000 acre-feet was cut by 13,000 or about 3.7%. Mexico’s 1.5 MAF allocation was reduced by 5% or about 75,000 acre-feet. All of these cuts were mandated by two agreements among the seven states, in 2007 and 2019, triggered when water levels at Lake Mead reached critical low levels.

An acre-foot of water is the amount of water it would take to cover one acre of land with one foot of water, or about 326,000 gallons of water. That’s enough on average to provide two families of four with enough water for a year.

A second round of cuts in 2022 meant Arizona lost another 80,000 acre-feet annually, with 4,000 acre-feet in cuts to Nevada and a 7% reduction to Mexico, or 105,000 acre-feet. Arizona’s Central Arizona project, the 336-mile system that supplies Colorado River water to the state’s most populated regions, shouldered almost all of Arizona’s cuts.

Hobbs wrote that state-level action cannot substitute for shared responsibility for all seven states.

“A durable agreement requires meaningful, reliable and verifiable contributions from all states,” she wrote. “Without that balance, the burden of risk shifts unfairly and undermines the prospects for consensus,” a nod to concerns that a new operating guideline could mean Arizona could once again be hit with more cuts to its allocations, as the state with the most junior water rights in the basin.

The meeting comes more than two months after state negotiators failed to come up with even the framework of an agreement on how to manage the river.

On Jan. 9, the Bureau issued a draft Environmental Impact Statement that offered five operational alternatives for managing the river. The bureau did not decide on a preferred alternative, hoping for a “potential collective agreement” among the seven states.

The draft impact statement was published in the Federal Register on Jan. 16, starting a 45-day public comment period that ends on March 2.

In a statement, Andrea Travnicek, the assistant secretary at the Department of the Interior for water and science, said the department “is moving forward to ensure environmental compliance is in place so operations can continue without interruption when the current guidelines expire.”

She added that the river and the 40 million people who rely on it cannot wait.

“In the face of an ongoing severe drought, inaction is not an option,” she said.

The divisions between the Upper and Lower basins center on how much each will contribute during drought. At issue are water cuts into the foreseeable future, the result of a 25-year drought that has reduced the river’s annual flow by millions of acre-feet.

The river once provided more than 16 million acre-feet of water per year to the seven states and Mexico, but 25 years of a historic drought, believed to be the worst in a millennium, has reduced those flows to less than 12 million acre-feet annually. That matters because each basin is entitled to about 7.5 million acre-feet on average per year.

As to the Jan. 30 meeting, news reports indicated there’s still a divide between the Upper and Lower basin states, with Arizona on one end and Colorado on the other.

The New York Times reported Arizona and California leaders “expressed optimism after the meeting that a consensus over a plan to share water appeared ‘achievable.'”

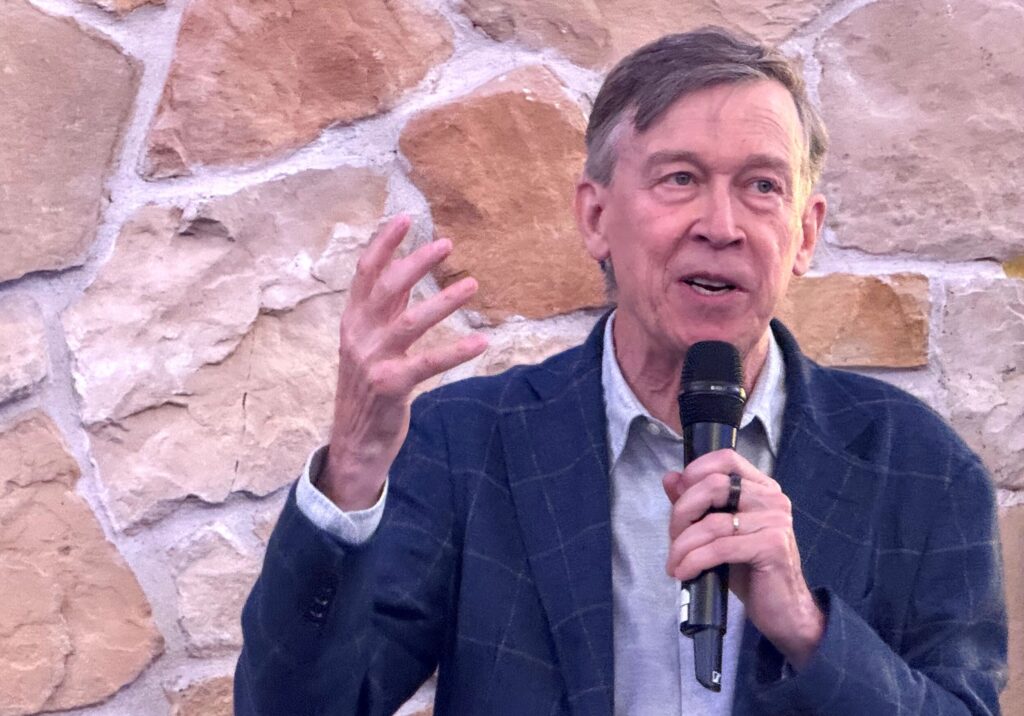

But Colorado officials, which includes Gov. Jared Polis and Commissioner Becky Mitchell from the Upper Colorado River Commission, “stood firm in their reluctance to accept mandatory water use cuts — a major sticking point that could remain in the way of a compromise,” the Times wrote.

The governors and the federal government are trying to avoid a situation where the impasse lands in court, with years of litigation ahead while the situation on the river becomes even more critical.

A joint statement issued by the governors said the meeting gave each governor an opportunity to explain their position on the river issue.

“All acknowledged that a mutual agreement is preferable to prolonged litigation. Importantly, the governors will continue to seek an agreement that helps provide certainty to the entire basin for the short and long term, including as it relates to federal funding of water projects.”

Polis said in a statement that he “defended our mighty Colorado River in the corridors of power in Washington, D.C. I always fight to defend our water, whether it’s at the Department of Interior, Congress, or the courtroom.”

He called the discussion productive, and said the state had already offered “sacrifices” to ensure the river’s viability.

Colorado, which holds the most senior water rights among the upper basin states and receives the largest allocation, has long maintained that it already takes less water than allowed under the current operating guidelines and that Colorado and its upper basin partners will not agree to reductions.

“One thing is certain: We’ll have less water moving forward, not more,” said New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, whose state is one of the four in the Upper Basin.

“So, we need to figure this out,” she said. “There is still a lot of work ahead to get to an agreement, but everyone wants an agreement, and we’ll work together to create a pathway forward.”

What makes the situation worse: this year’s snowpack. The Colorado River headwaters, which start in Rocky Mountain National Park, rely on snowpack as its main source of water. But below-normal precipitation and warmer temperatures through January, primarily in the central and northern mountains, have meant snowpack is at its lowest level in at least 20 years, according to the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Mitchell did not respond to a request for comment.