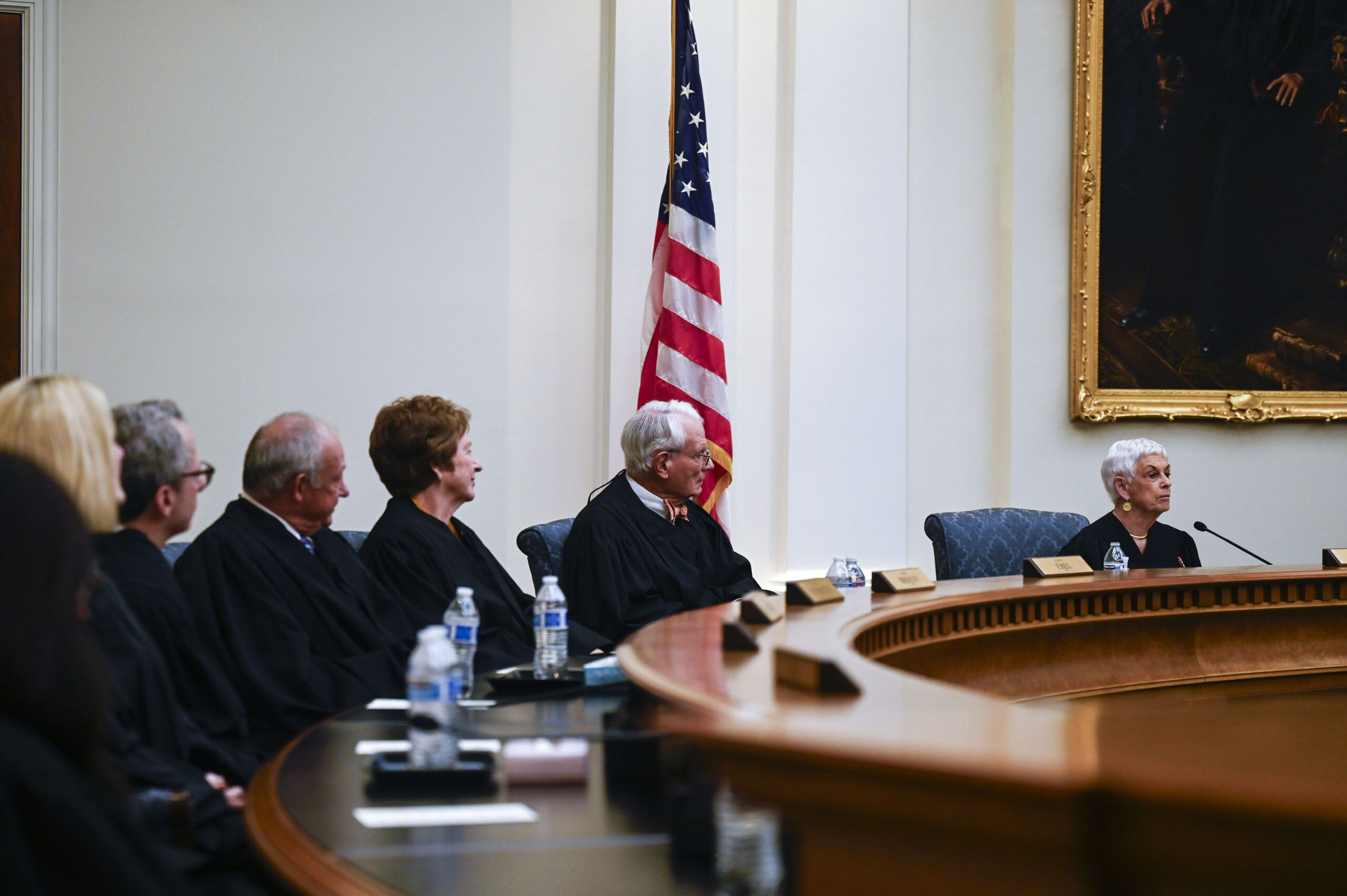

10th Circuit to address resentencing of probation violators in rare all-judges hearing

The Denver-based federal appeals court agreed on Thursday to hold a rare all-judges hearing to determine the proper procedure for resentencing a criminal defendant who has violated the terms of his probation.

In the federal appellate courts, the vast majority of cases are decided in three-judge panels. Occasionally, the courts will vote to have all judges hear a case, known as an “en banc” review. Historically, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit receives approximately 190 requests per year, but grants fewer than one on average.

A key feature of en banc review is a circuit court’s ability to overrule prior precedents established in panel decisions, which are binding on the court itself. The chances for full-court review are better when there is a conflict between decisions or the 10th Circuit is an outlier on a specific issue, with ramifications beyond the case being litigated.

In the case of Malachi Mathias Moon Seals out of Colorado, his attorney persuaded a majority of the circuit’s 12 judges to review a relatively recent precedent governing the resentencing of probationers. Although the judge who authored the opinion offered a vigorous defense of his analysis, Moon Seals alleged that the resulting procedure put the 10th Circuit fully out of line with other circuits nationwide.

The underlying dispute stems from the circuit’s 2022 opinion in United States v. Moore, in which defendant Jamaryus Moore pleaded guilty to robbery and received a probationary sentence. After Moore violated the terms of his probation, he was resentenced to prison. In addressing the specific way the trial judge imposed the sentence, the 10th Circuit panel put forward a two-step process for resentencing probation violators.

First, wrote Judge Gregory A. Phillips, a judge must reimpose a sentence for the underlying crime, without regard to events that occurred since the probation began. Second, the judge adds an increment to the sentence for the probation violation.

Two years later, Moore was back at the 10th Circuit following his resentencing. A different panel upheld the precedent-setting nature of the two-step approach, but clouds began to form on the horizon.

Senior Judge Michael R. Murphy wrote that the panel was “not without some doubt” about that process. If it had the freedom to decide differently, “this panel might very well” go with a different procedure.

Finally, Moore sought consideration of his case by the entire 10th Circuit. No judge voted to go en banc, but Judges Timothy M. Tymkovich and Joel M. Carson III agreed the sentencing method “should be addressed in a future case.”

While Moore’s appeal unfolded, Moon Seals pleaded guilty to numerous counts of sending threats to federal officials, including U.S. Rep. Lauren Boebert. Despite the sentencing range being 33 to 41 months in prison, both sides asked that Moon Seals be put on probation instead.

U.S. District Court Judge Charlotte N. Sweeney initially balked. But she understood Moon Seals’ longstanding brain injury played a role in his conduct, and begrudgingly imposed probation so his condition could be addressed out of custody. Moon Seals immediately resumed sending threats, amounting to a probation violation.

Although the 10th Circuit had decided the Moore case, Sweeney did not follow the two-step procedure in resentencing Moon Seals. Instead, she appeared to believe she could resentence him under either the range for his original offenses or the range for a probation violation. Relying on the original range, Sweeney imposed 36 months in prison.

The 10th Circuit panel hearing Moon Seals’ appeal agreed Sweeney did not follow the procedure, but it upheld his sentence in October. In doing so, Phillips, who authored the decision in Moon Seals’ case, issued an unusual second opinion to defend his prior reasoning behind the two-step sentencing method and potentially ward off full-court reconsideration.

Phillips traced the history of the sentencing law, arguing Congress changed it in the 1990s after the then-chair of the U.S. Sentencing Commission wanted to overturn an appeals court decision capping the sentence a probation violator received to the original range for the underlying crime.

“The legislative history precisely shows that Congress,” wrote Phillips, “created the two-step sentencing procedure set forth in Moore.”

In petitioning the 10th Circuit for en banc review, public defender Jacob Rasch-Chabot argued the historical evidence undermined the idea of a two-step process.

“Based on the relevant statutes, guidelines, and legislative history, all ten other circuits have held that the sentencing range (specific to probation violations) applies to the entirety of the sentence imposed upon revocation of probation,” he wrote.

In a Jan. 22 order, the court announced it will decide whether to stick with the two-step method for federal probation violators in the circuit’s six-state region. The circuit asked the government and the defense to address a series of other questions, including how a one-step resentencing would work.

The court’s clerk told Colorado Politics that the 10th Circuit does not reveal which judges voted which way on successful en banc petitions.

In addition to the circuit’s roster of 12 judges, Murphy, the semi-retired senior judge who expressed prior doubts about the two-step method, was one of the members of Moon Seals’ appellate panel. Although he was entitled to join the en banc hearing, he chose not to participate.

The case is United States v. Moon Seals.