With guidelines expiring, federal agency releases draft plan for Colorado River operations

Two months after the seven states of the Colorado River basin failed to reach consensus on managing the waterway, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation issued a set of proposed alternatives.

The alternatives are familiar concepts, including “no action” — an unlikely scenario — and certain levels of coordination, including voluntary measures, among the states. One option is driven by the historical, natural flow at one of the reservoirs.

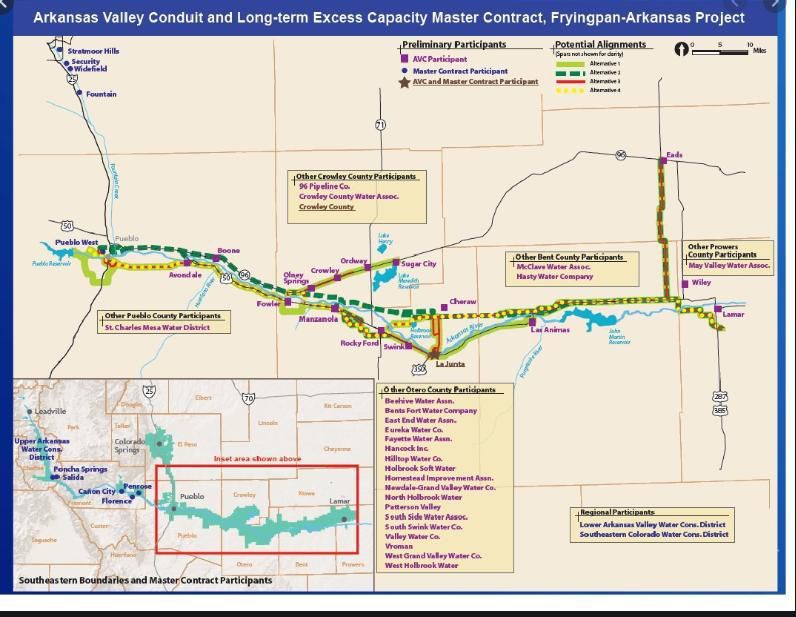

Current operating guidelines for the river that supplies water to seven states, 40 million people, 30 tribes and 5.5 million acres of agricultural land will expire at the end of 2026.

On Jan. 9, the Bureau issued a draft Environmental Impact Statement that evaluates five operational alternatives for managing the river. The Bureau did not decide on a preferred alternative, hoping for a “potential collective agreement” among the seven states.

In a statement, Andrea Travnicek, the assistant secretary at the Department of the Interior for water and science, said the department “is moving forward to ensure environmental compliance is in place so operations can continue without interruption when the current guidelines expire.”

She added that the river and the 40 million people who rely on it cannot wait.

“In the face of an ongoing severe drought, inaction is not an option,” she said.

The Bureau of Reclamation had set a deadline of Nov. 11 for at least a framework of an agreement from California, Nevada and Arizona for the lower Colorado River basin, and Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico for the upper basin.

The divisions between the upper and lower basins center on how much each will contribute during a drought. At issue are water cuts into the foreseeable future, the result of a 25-year drought that has reduced the river’s flow by millions of acre-feet.

In a statement last month, the Upper Colorado River Commission noted the Upper Basin states “already take significant mandatory and uncompensated reductions, averaging about 1.3 million acre-feet per year … While the Lower Basin has also reduced uses, releasing more water from reservoirs than flows into them is resulting in declining reservoir levels at Lake Powell … and Lake Mead.”

Both basins are allotted 75 million acre-feet of water over a 10-year period. However, since 2019, when a drought contingency plan was put into place, allotments have been reduced, primarily to Arizona, which has the most junior water rights in the lower basin.

The Colorado River hasn’t produced that much water in years. In a good year, maybe 12 million acre-feet is available.

The Bureau of Reclamation estimated that, by 2035, the river will provide only about 11.4 million acre-feet of water — and down to 11 million by 2060.

The bureau said last week that current water levels at the river’s two main reservoirs, Lake Powell for the upper basin and Lake Mead for the lower basin, are at 27% full and 33% full, respectively.

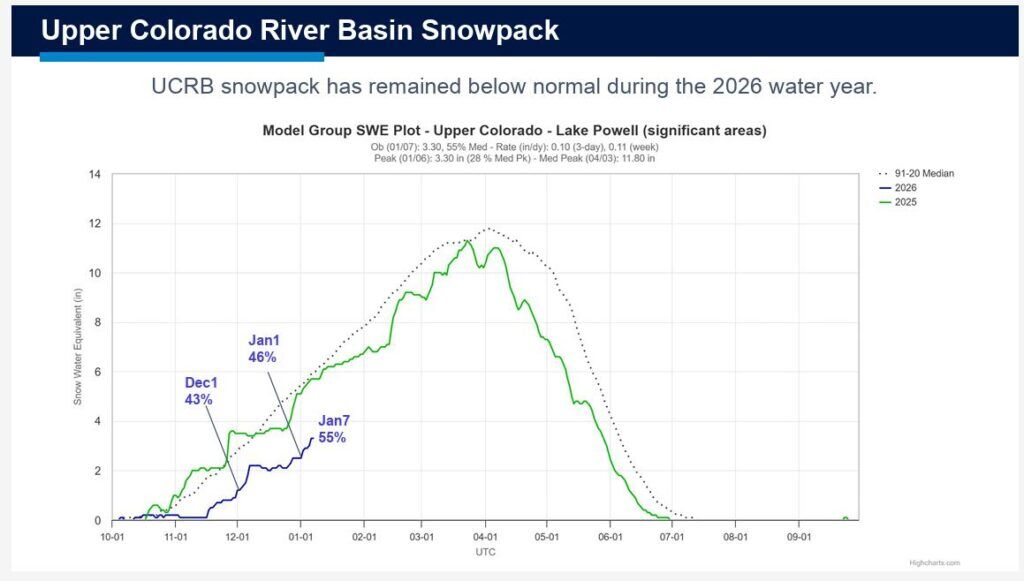

A recent forecast from the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center said snowpack in the 2026 water year for the upper Colorado River Basin is at its lowest recorded level in 25 years.

The draft impact statement was published in the Federal Register on Jan. 16, starting a 45-day public comment period that ends on March 2.

The next set of operating guidelines must be in place by Oct. 1 this year, according to the Bureau’s statement. That’s the start of the 2027 water year.

The Bureau has been without a Senate-confirmed commissioner since President Donald Trump took office a year ago. His only nomination for commissioner was pulled in the wake of pressure from Republican senators, including the chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, who would have held the confirmation hearing. Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, delayed the hearing for three months for Ted Cooke, who had previously been the head of the Central Arizona Project, which supplies water from the Colorado River to metro Phoenix. Lee and the White House declined to comment on Cooke’s withdrawal.

Cooke told Colorado Politics in October that he had been told there were concerns about his background check, but he was never told what those entailed.

In the meantime, Scott Cameron, who had been the acting assistant Interior secretary for water and science, was named on Oct. 2 to be the acting commissioner by Interior Secretary Doug Burghum.

Cameron said in a statement on Jan. 9 that “given the importance of a consensus-based approach to operations for the stability of the system, Reclamation has not yet identified a preferred alternative.”

However, he continued, “Reclamation anticipates that when an agreement is reached, it will incorporate elements or variations of these five alternatives and will be fully analyzed in the Final EIS, enabling the sustainable and effective management of the Colorado River.”

The five alternatives in the draft impact statement are:

• No action, a return to the guidelines that existed prior to 2007 and unlikely to be considered

• Basic coordination, an alternative designed to be implementable without agreements among basin users regarding distributions of lower Colorado River mainstream shortages, storage and delivery of conserved water from system reservoirs or other voluntary agreements

• Enhanced coordination, based on proposals and concepts from specific basin tribes, federal agencies and other stakeholders

• Maximum operational flexibility, proposals submitted by conservation organizations

• Supply driven, based solely on historical natural flow at Lake Powell

The Bureau noted it would not consider the separate proposals submitted by the upper or lower division states in 2024 and 2025 or another proposal from the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona.

The Upper Colorado River Commission announced in December that it hoped negotiations would produce a full package agreement to be delivered to the Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Reclamation by Feb. 14.

Becky Mitchell, Colorado’s representative on the commission, said in that December statement, “There’s an important difference between protecting lawful uses and asking the rest of the Basin to subsidize continued overuse.”

“Rhetoric that treats emergency federal action or Upper Basin storage as a backstop for Lower Basin demand distorts both the Compact and the crisis. There’s a growing gap between the political rhetoric we’re hearing and the hydrological reality we’re living with,” she said. “The Colorado River does not respond to press releases or historical entitlements — it responds to snowpack, soil moisture and temperature.”