Direct primary care offers affordability, access as health care costs rise

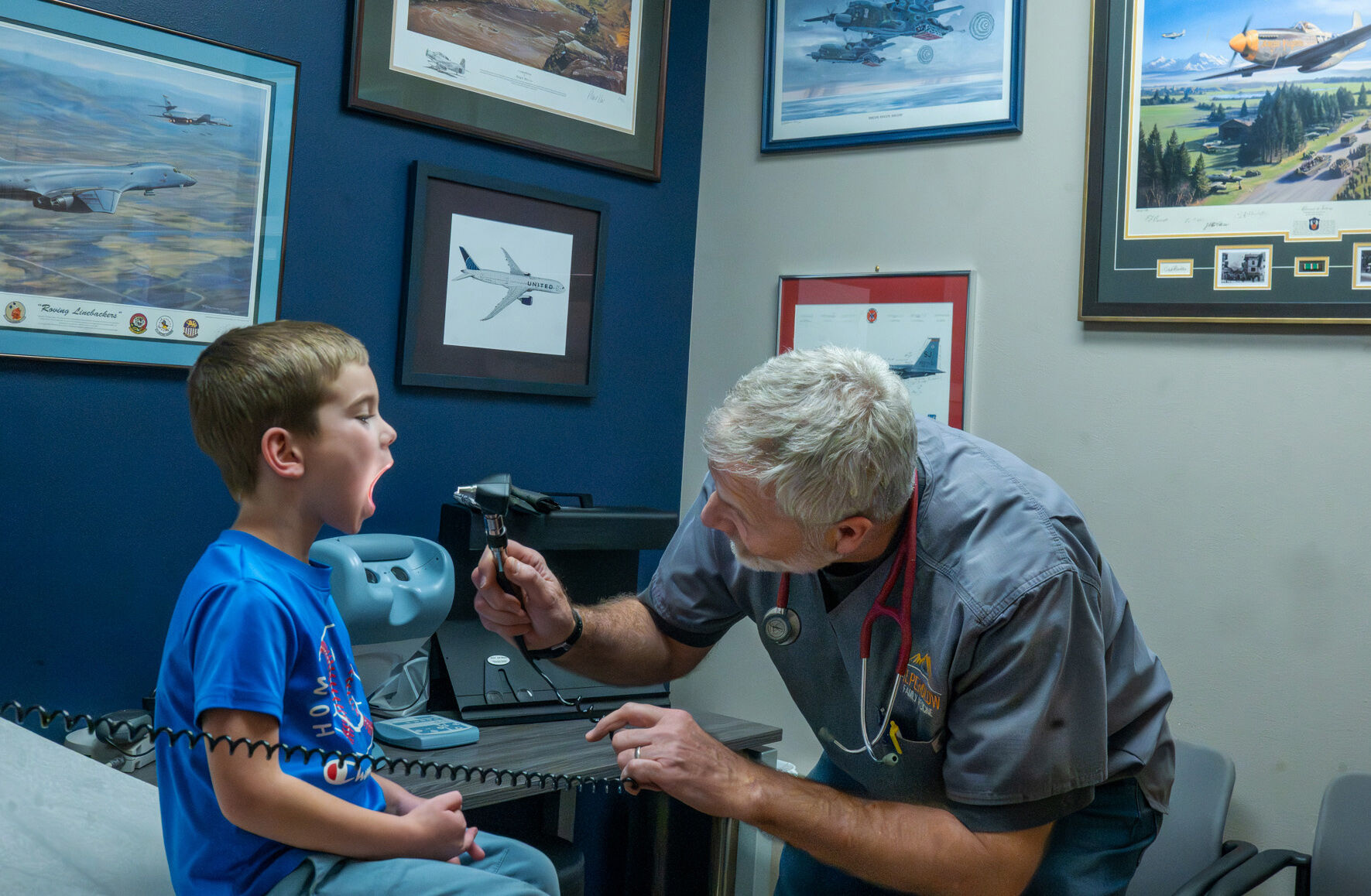

In the Air Force, Dr. Alex Schloe used to see 22 patients a day for a primary care appointment where he would spend five to 10 minutes with each person.

“It can be frustrating for the patient and for the doc,” he said.

Across many primary care clinics who rely on insurance for payment, the model is similar with doctors seeing as many patients as possible and often sending them along to specialists for care that could be done in-house, if the doctors had more time. The high number of patients, sometimes 35 a day, also leads to burnout among physicians, explained Schloe and Dr. Dave Rogers, who run Alpenglow Family Medicine.

Rogers founded the direct primary care clinic off West Fillmore Street eight years ago to cut insurance out of his business model, in part because it was soaking up so much of his time.

In one case, he spent 45 minutes arguing with an insurance representative over whether a patient could get a blood test for $12, he said.

Through the direct primary care model, the two physicians offer 30-minute appointments as often as the patient needs for a monthly fee. The highest monthly fee for an individual is $115 for an adult over 40, according to the clinic’s website.

The office also offers lab tests at cost, cutting out the insurance markup, which can be 1,000%, they said. Many prescriptions can be picked up in the office as well.

While it does not appeal to everyone, for those who might pay $8,000 out of pocket, for example, to meet their deductible before insurance kicks in, the direct primary care model can save patients money because the cost of their care won’t come close to the price of their deductible, Schloe said.

In one case, a patient paid about about $6,000 for their child to get a simple prescription and a chest X-ray at the emergency room, when all of the care could have been handled at the primary care office, Rogers said.

The doctors still recommend patients have insurance if catastrophe strikes, such as a cancer diagnosis or a massive car crash. The direct primary care model is also not open to those with Medicare.

But it could be a practical solution for those who will see their monthly premiums double on average through Connect for Health Colorado because Congress did not extend tax credits needed to keep costs down, according to the state Division of Insurance. The agency also expected 75,000 people to lose their insurance because of the price increases. In early December, the agency said the number could be lower based on strong enrollment trends.

When large numbers of people lose insurance, it hurts the whole health care system, said Mannat Singh, executive director of the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative.

Those people are more likely to end up in emergency rooms and left with a bill they can’t pay, she explained. Those costs are then passed along to those who can pay.

However, she doesn’t see direct primary care as a good option for patients because the membership fees only cover the care provided in the office.

“It doesn’t work to cover that gap that is created when somebody is uninsured,” she said.

Critics of direct primary care, like Singh, also point out direct primary care could pull doctors away from traditional primary care offices and make it harder to get an appointment.

However, Dr. Cory Carroll, another direct primary care physician in Fort Collins, noted primary care physicians’ high patient load leads to burnout, contributing to the shortage.

The model also creates direct accountability between the doctor and the patient, he said.

“I have to have my patients trust me and be willing to pay me out of their own pocket, which means I better do a damn good job of taking care of them,” he said.

Schloe and Rogers encourage their pateints to have insurance.

But they also don’t turn away people who don’t have it.

The office can provide about 85% of a patient’s needs and prevent them from needing to go to the hospital, Rogers said.

Some of the procedures the physicans can complete in their office include treating joint pain with injections, removing moles, providing contraceptives, working on mental health and managing long-term conditions like diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, often called COPD, among many other services.

The model can be a good fit for patients with a chronic condition because they can come to the doctor once a month if necessary, to work on issues like medication management, an option that is generally not open to those working through traditional insurance, Rogers said.

It helps soothe the tension patients have about coming to the doctor.

“When they come to us, we hear this, like, sigh of relief,” Rogers said.

The key is more time to work with patients, Rogers and Schloe said.

Schloe saw it work wonders as a doctor in the Air Force. A canceled appointment allowed him to spend about 15 minutes of additional time with a patient struggling with diabetes, high cholesterol, high blood pressure and obesity. She was also struggling with her weight. At the time, she was 330 pounds.

The patient told Schloe, she wanted to start exercising but she didn’t know where to start. He advised just walking in place and then after a couple days going around the block and then two blocks and gradually building from there.

Without the additional 15 minutes, he likely would have ordered some labs and moved on to his next patient without having a longer conversation.

Before she left Schloe’s care, she had lost 150 pounds and no longer needed any medication. She has since run a half-marathon.

“That is an example of what direct primary care can be for every patient,” he said.