Can you afford to live in Denver? | FISCAL ROCKIES

| Editor’s Note: Once among the nation’s fastest-growing economies, Colorado today confronts mounting challenges that threaten its momentum. This series reveals how a state once defined by prosperity is navigating economic cliffs and ridges. We explore the impact of increased regulations, tariffs, shifting tax policies, the high cost of living and widening urban–rural divides have on businesses, workers, and communities. The series also highlights the push to leverage Colorado’s outdoor economy — one of its most valuable assets — for renewed growth, while working to attract industries like quantum and aerospace while capitalizing on unique industries that call Colorado home. |

Colorado’s median household income in 2024 was more than $97,000, 19% higher than the national average.

That number, combined with the state’s below-average poverty rate, indicated a lucrative lifestyle for most Coloradans.

But beneath those gaudy statistics, other cost-of-living metrics show that Colorado — more specifically, Denver — is one of the most expensive places to live, both compared to the national average and to other cities with a comparable population.

The public regional price parity data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis – which measures the differences in price levels across locations for a given year and expresses that difference as a percentage of the overall national price level – reveals that Denver was a little over 5% more expensive than the national average by the end of 2023.

Data from Oklahoma City, the nearest major U.S. city to Denver by population, is also included on the chart for further nuance. Its overall cost of living, by contrast, was about 10% below the national average by the end of 2023.

Not everything in Denver was about 5% more expensive than the national average through 2023. Goods, in particular, cost just about 1.5% more than the national average.

Housing, though, is where Denver truly separated itself from the U.S. and Oklahoma City. The Mile High City’s housing costs were 46% above the national average through the end of 2023.

As costs of living in the Denver area and throughout Colorado have risen, the city and state’s population growth has slowed.

Data from the Colorado Demography Office shows that the state’s population increased by just over 36,000 in 2023, a far cry from the 76,000 it averaged each year from 2010 through 2019. Denver, too, saw just over 16,000 new residents that year, nearly a third of the 45,000 it averaged during that same period.

The high cost of living could be why those who previously may have been interested in moving to Denver are now more cautious about doing so, said Colorado State University economics professor Anders Van Sandt.

“People, particularly young people, are becoming more interested in mid-size cities that aren’t huge but offer a decent quality of life,” Van Sandt said. “If that gets eroded by the high costs of living, then they’re going to look elsewhere in Colorado or outside of Colorado for a quality of life they can afford.”

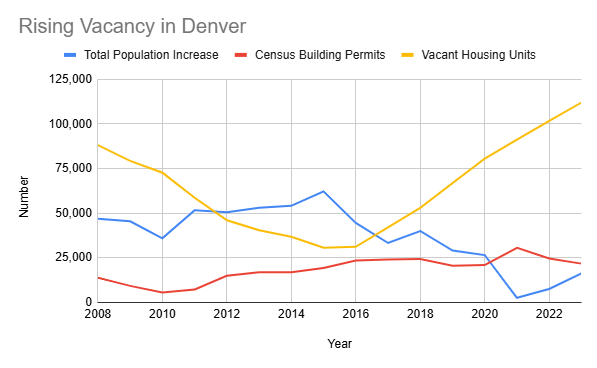

The sudden decrease in population growth in Denver has led to a boom in vacant residences, despite a relative plateau in new building permits, according to that same data. In 2018, the last year Denver’s annual population growth exceeded 40,000, the city had about 53,000 vacant housing units.

By the end of 2023, that number had ballooned to nearly 112,000.

Denver’s soaring living costs aren’t just affecting young people. They are affecting residents of all ages.

Deborah Parsons, 77, moved to an apartment complex in 2019 with her partner and teenage grandnephew, who, she said, suffers from psychological problems that have previously led to him being hospitalized.

Between her climbing rent, the necessary maintenance of her 15-year-old car, and the medical care she received after she was hit by one, Parsons’ living costs have been anything but cheap, she said.

Despite a college education from the University of Iowa and a career in the designer clothing industry, Parsons receives benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and frequents local food banks to feed her family, she said.

“I am attempting to utilize all the resources that are available to me to help my family survive,” Parsons said. “And I try to help any others I can.”

Parsons noted that she shops in a “thrifty” manner, seeking sales and other deals to maximize her money. But that mentality has also led her not to eat as much as she used to, she said.

“At one time this year, I was diagnosed as ‘failure to thrive,’ which means I wasn’t eating enough to survive,” Parsons said. “I hope it’s not that I have starved myself. I’m not hungry. I don’t eat a lot of what I used to eat.”

Parsons isn’t alone. An estimated 53% of Coloradans are eligible for SNAP benefits, falling within the income limit of 200% of the federal poverty line, which was $64,300 for a family of four as of January, according to feedingamerica.org. In Denver County, that number increases to 56%.

By contrast, 43% of the population in Oklahoma County — where Oklahoma City is located — is below the maximum threshold to be eligible for SNAP benefits, according to the same data. Forty-five percent of those in Sedgwick County, home to Wichita, Kansas, meet the same eligibility.

The cost of a meal is also more significant in Denver County, with its $4.09 average for food-secure individuals pacing well above that of Oklahoma County ($3.65), Sedgwick County ($3.58) and the U.S. average ($3.58).

Van Sandt noted that in times of food scarcity, people will either cut back on how much they buy or choose to purchase cheap, shelf-stable food that tends to be more ultra-processed. That results in declining revenues not only for grocery stores but also for surrounding businesses.

“We’re seeing just an economic ripple effect in these communities in people not having enough money for food,” Van Sandt said. “If you can’t buy food, there’s not much you can substitute for it. This is changing our rural economies and how money flows in our rural economies, and it’s going to have lasting effects not only for small businesses that sell food but for small businesses that sell other necessity items for consumers in their community.”

Rural communities, too, can feel the cost-of-living crunch more significantly than urban cities, Van Sandt said.

“Even though there’s a higher overall number of impoverished people in urban places, there’s a higher rate in rural places,” Van Sandt said. “People may have a lower cost of living out there, but they might have selected to live out there because of that lower cost of living. So, if you increase costs, it’s still going to hurt.”

Read more from the Fiscal Rockies series: