‘Utterly no precedent’: Federal judge expresses concerns about Jeffco’s early appeal in jail death case

A federal judge shared his concerns on Monday about Jefferson County’s appeal of a routine procedural order in a constitutional rights case, which the plaintiffs argued could spawn appeal-related delays in countless lawsuits against the government.

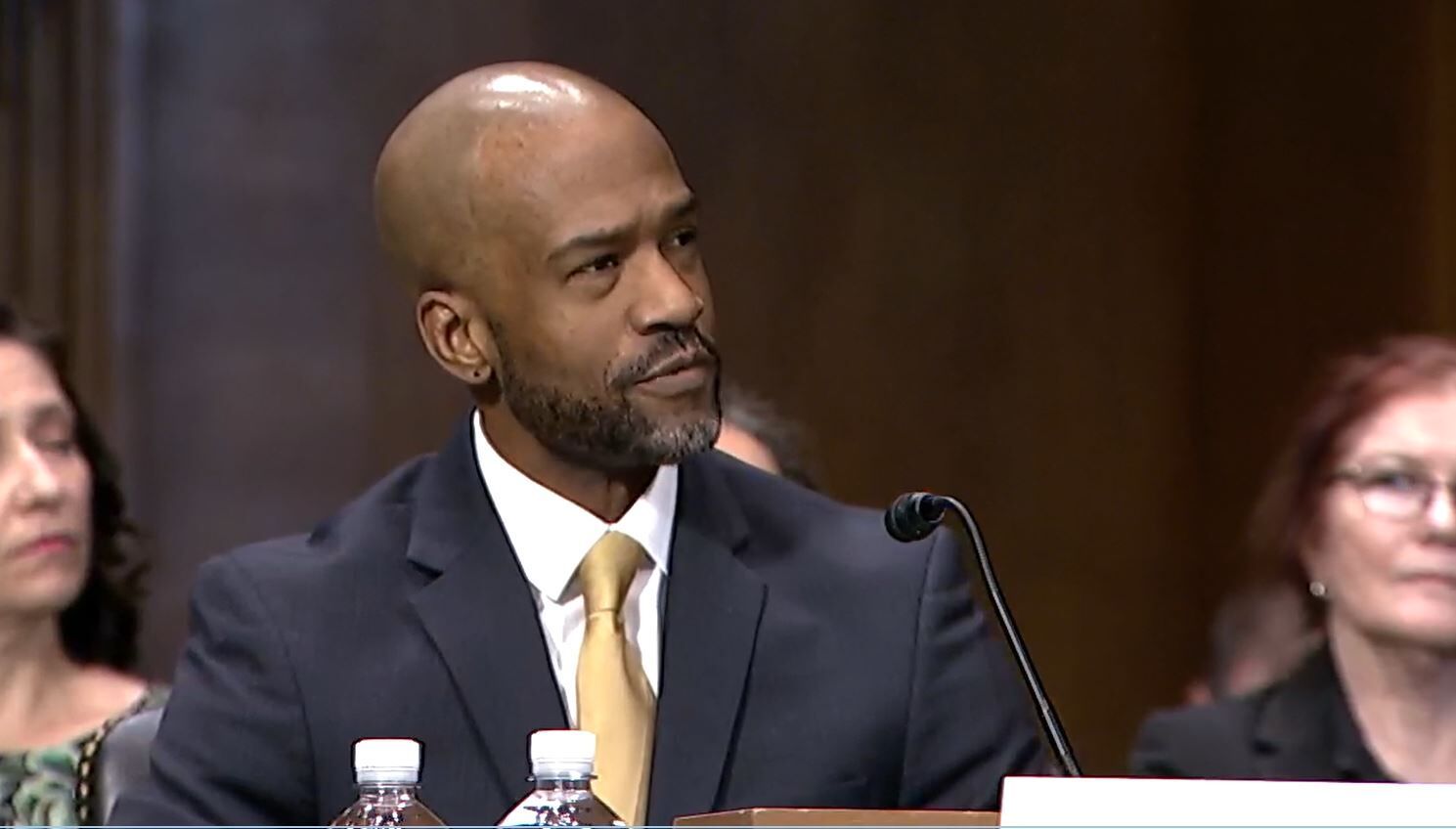

During a hearing, U.S. District Court Judge S. Kato Crews noted he could find no decisions backing up the county’s position that judges must halt, or stay, civil lawsuits until they determine whether government officials are entitled to immunity. Consequently, he took offense to Jeffco’s claim that Colorado’s federal judges have developed a habit of improperly “citing themselves rather than binding precedent” when deciding whether to stay cases.

“I take that seriously. I think that gets thrown out too easily these days, accusing courts of not following precedent,” he said.

In the underlying lawsuit, the surviving family of James Purdy has sued Jefferson County, its elected sheriff, several jail personnel and the jail’s medical contractor. The family alleges Purdy, 76, died in custody after numerous falls that jail staff knew about, yet failed to prevent. The claims include violations of Purdy’s constitutional right to adequate medical care, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and Colorado’s constitution and laws.

The Jeffco sheriff’s defendants moved in April to dismiss the claims against them. For the federal constitutional claim specifically, they invoked qualified immunity, a judicially created concept that shields government employees from civil lawsuits unless they violate a person’s clearly established rights.

Government defendants can assert qualified immunity early on with a motion to dismiss, or they can raise it in a motion for summary judgment after the discovery of evidence has run its course. Notably, unlike most orders that can only be appealed at the conclusion of a case, a defendant can appeal a trial judge’s order denying qualified immunity immediately.

Shortly after the Jeffco defendants filed their motion to dismiss, they also asked the court to stay the case until Crews could determine whether the individual employees were entitled to immunity. U.S. Magistrate Judge Timothy P. O’Hara responded that he was “not persuaded” Jeffco demonstrated a need to pause the proceedings. Instead, he allowed for “staggered” witness depositions to occur between September and November.

Jeffco challenged O’Hara’s decision to deny a stay, but Crews found the order justified.

“Judge O’Hara’s order is consistent with a long line of cases that find the assertion of qualified immunity alone does not entitle a defendant to a stay,” he wrote on Oct. 7. “Moreover, due to the related state law claim which affords no Defendant qualified immunity, the Sheriff Defendants will have to participate in discovery anyway.”

Then, Jefferson County did something unusual: It immediately appealed Crews’ decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit.

Under the county’s logic, a key purpose of qualified immunity is to protect government employees from “the ordinary burdens of litigation.” If defendants have to sit for depositions, they are experiencing the burdens of litigation and, effectively, have been denied qualified immunity. Therefore, defendants are entitled to appeal immediately.

“There’s utterly no precedent for what they are doing here,” Darold W. Killmer, the plaintiffs’ attorney, told Crews.

He asked Crews to label Jeffco’s appeal “frivolous,” a move that would enable Crews to forge ahead with the case even as the 10th Circuit resolves the appealed issue. In doing so, Killmer asserted that government defendants already seek to delay civil rights cases. If the courts treated other types of rulings against the government as entitled to immediate appeal, it would be an opportunity for further setbacks.

“Families are grieving. They are certainly far less resourced than the defendants,” Killmer said. “A ruling in favor of Jefferson County on this will open a Pandora’s box for all defendants.”

Crews, meanwhile, grappled with the mechanics of Jeffco’s appeal. If his denial of a motion to stay was the equivalent of him denying qualified immunity, “what’s the motion to dismiss worth then?” he wondered. “Why would we then spend time on a motion to dismiss that raises that issue?”

Assistant Deputy County Attorney Rebecca P. Klymkowsky, in denying her office purposefully seeks to delay cases, responded that “the law is very clear” about public officials’ entitlement not to be burdened with litigation where they are immune. Practically, requiring the defendants to give testimony was one such burden.

“Qualified immunity was not any part of the analysis or anything I ruled upon,” countered Crews. “As I understand your argument, this would apply in any cases where qualified immunity is raised. That once a motion to dismiss is filed, an automatic stay of discovery should enter as to those defendants. Is that your view?”

“I don’t know that anyone has explicitly said that stays in this context are automatic,” Klymkowsky responded.

Crews said he will issue a written order on the plaintiffs’ request to declare Jeffco’s appeal frivolous.

The case is Estate of Purdy et al. v. Jefferson County, Colorado et al.