Food banks in Denver area struggle to meet the need

The line of people outside the Adams County Food Bank wrapped around the building as the clock ticked toward 10 a.m. Thursday.

Some held grocery bags. Others sat on the ground. All wore the same saturnine expression.

That sight has been common at a food bank that draws most of its clientele from surrounding cities, including Denver and Aurora, since Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits were delayed in early November, according to Executive Director Stephanie Wayne.

“The past couple weeks have been really, really busy,” Wayne said, watching volunteers sort through food items and pack boxes in the food bank’s warehouse. “Typically, we serve about 1,200 families a week. We’ve been doing 1,400 recently.”

Wayne estimated that the organization usually handles about 80 new families per week. Two weeks ago, that influx rose to about 170 families. Last week, it inched up to 191.

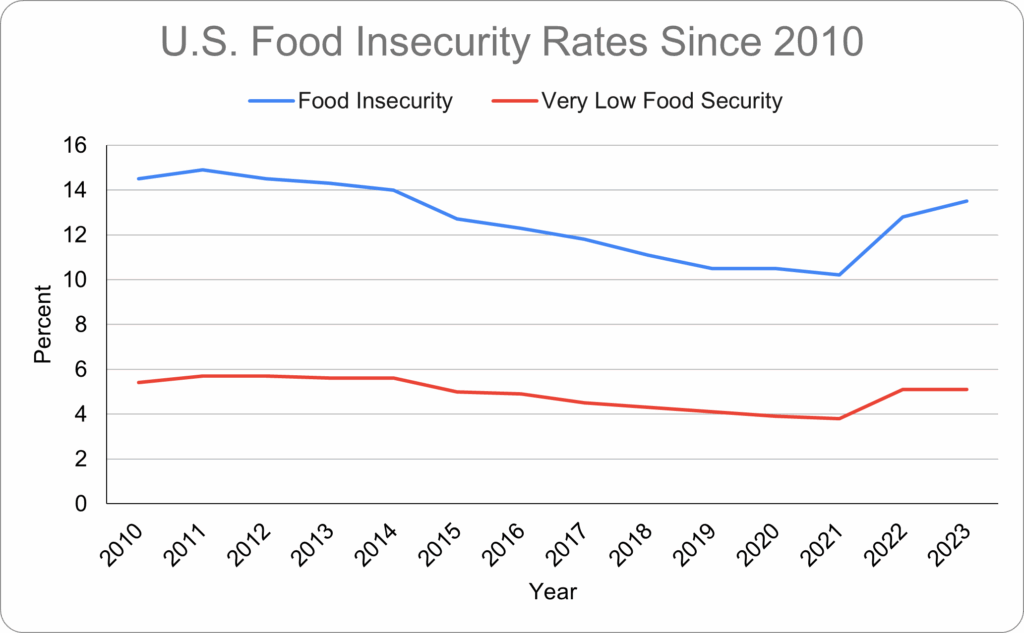

U.S. “food insecurity” has been at a near-decade high, according to data through 2023 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Broadly speaking, food insecurity refers to the condition in which households have limited or tentative access to sufficient food. The USDA defines it in two ways – “low food security,” referring to “reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet,” and “very low food security,” which means “multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.”

Another food bank official said the sudden influx is but a symptom of a bigger problem.

“I wish I could say it’s just the shutdown or SNAP, but people are coming to us from different walks of life,” Carl Esquivel of the Salvation Army Aurora Corps told The Denver Gazette. “There are many families already living paycheck to paycheck and working two or three jobs. So, when things like this happen, it exacerbates their ability to support themselves.”

Added Food Bank of the Rockies CEO Erin Pulling, “Even before the government shutdown, we were already responding to the highest levels of food insecurity in more than a decade.”

Food Bank of the Rockies, the largest hunger-relief organization in the Rocky Mountain region, serves all 23 counties in Wyoming and 32 counties in Colorado.

It both provides food directly to residents through mobile pantries and distributes food to more than 800 nonprofit partners.

“You can just tell that everybody’s stressed,” Wayne said, adding that stress, at times, has boiled over into arguments about parking and where in line people are standing. The Adams County Food Bank has placed more volunteers outside the facility to help mitigate arguments.

“People were calling and just crying. You’re up at night thinking about this,” Barbara Moore, founder of Jeffco Eats, said Friday behind tears.

Alondra Burciaga, who was at the Village Exchange Center pantry on Nov. 6 to get food, said, “I’ve seen many people looking for food. There’s been plenty of people searching for food and other options.”

Added Jonathan Jose Gonzalez, another food recipient at the pantry, “I’m really very thankful for places like this.”

Funding cuts to the USDA earlier in the year reduced the volume of food received by Food Bank of the Rockies by 7% or enough for about 14,000 meals per day, according to Pulling.

“Right now, USDA food is about 10%-15% of our total food volume,” Pulling said. “In comparison to the height of COVID, when we as a country did an excellent job meeting people’s food security needs, USDA food was 50% of our food supply.”

The U.S. government had deployed trillions of dollars in bailout money during the pandemic, when state and local officials limited or banned gatherings, shut down businesses and closed schools.

Increased philanthropic support has helped the organization make up that gap and a $10 million commitment from the state government has given it more purchasing power for wholesale food, Pulling said.

But even with those additional resources, the organization’s ability to serve local food banks and pantries throughout both Colorado and Wyoming remains stretched thin, Pulling said.

“This is way more than a strain. This magnitude of need right now is unlike anything we’ve faced in the organization’s 47-year history,” Pulling added.

SNAP IS BACK BUT DEMAND FOR FOOD REMAINS

SNAP benefits temporarily ceased amid the federal government shutdown, delaying food assistance to nearly 42 million people in the country and around 600,000 in Colorado.

The shutdown ended Wednesday, and full SNAP payments will resume, but they are just now getting out to recipients. State officials said full benefits are on the way.

“Even if SNAP benefits are reinstated in full for November, we know that more than 90% of recipients have less than a dollar left on their SNAP benefits by the last week of the month. Since people haven’t been receiving benefits in early-to-mid November, they’re in really difficult situations,” Pulling said.

Even with the full release of benefits, access to food will remain a major issue for thousands of Coloradans, officials in the food bank community said.

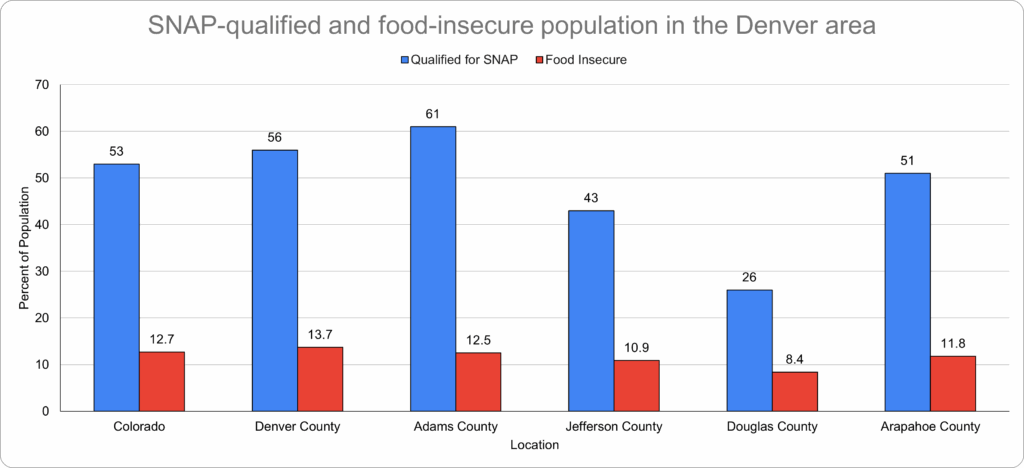

Hunger Free Colorado said while 9% of Coloradans receive SNAP benefits, about 11%, or about 733,000 Coloradans, face issues accessing food on a daily basis.

“Everyone will be playing catch up for a long time. This impact will trickle down and take a while to get through,” Wayne said. “The fear is always that everyone is fighting over the same money pot, nonprofit-wise. We would love to do more diapers and formula and household goods, but it’s not something in our budget or we can get right now. We don’t have the manpower or the money.”

Jeffco Eats, a nonprofit started in 2017, packs food and gives it to partners to fight child hunger. It provides food to 71% of Title 1 schools in the Jeffco Public Schools district and many recreation centers and libraries.

“I don’t even know what they’re doing” to get enough food even with SNAP benefits, Moore said of people needing assistance.

The shutdown-induced delay – Democrats and Republicans had blamed each other for the 40-plus day paralysis – brought to the fore anew the debate over food assistance.

On the one hand, some argue that the shutdown exposed America’s dependency crisis, noting the 42 million people who rely on food stamps. They say the food stamp program has created a “welfare trap,” a cycle that ultimately makes it difficult for Americans to break out of poverty, while costing taxpayers about $100 billion a year.

On the other hand, supporters say SNAP has served as a bulwark against hunger, that it has helped to stimulate the economy, and that it provides critical support to low-income Americans.

FOOD INSECURITY ACROSS THE REGION

Community Table, a grocery store-style pantry in Arvada, saw a surge of donated food as SNAP benefits were delayed in November.

More than 80% of its offerings one week were provided through donations, said CEO Sandy Martin and COO Rocky Baldassare.

Those donations managed to offset a reduction in food provided by The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), they said.

“The TEFAP numbers have definitely been going down during the new administration, and all its cuts to government programs,” Baldassare said, noting that the exact amount of food varies month to month. “We got 22,000 pounds this month, so not bad. The lowest we’ve gotten in a long time was probably around 19,000 pounds.”

The federal program usually provides over 30% of the food distributed by Colorado’s food banks, and recipients of SNAP benefits — as well as other federal assistance programs — are automatically eligible to receive that food, according to the Colorado Department of Human Services.

Food from TEFAP and Food Bank of the Rockies, as well as donations from grocery stores and individuals, make up about 85% of Community Table’s overall food intake, Baldassare said. The remaining 15% is purchased through grants and other funding. Community Table serves anyone west of Interstate 25.

Officials at Denver area food banks said financial donations are more effective than donating food items because they can use the money to buy more food in bulk for a lower price per individual item.

Jeffco Eats said its food budget had been cut in half before the November SNAP benefits were delayed and it was already seeing a significantly higher demand.

It will now have to raise over $50,000 before the end of the year to maintain the amount of food it provides.

“The Food Bank of the Rockies’ food supply went down over the last year and their prices went up like 15%,” Moore said.

Food Bank of the Rockies used to have around 20 web pages of food for pantries to choose from, and now it has two, according to Moore.

While Moore said she is unsure exactly how much the nonprofit’s needs went up during the SNAP benefits delay, she said several schools called for help.

She doesn’t like to exaggerate or guess about numbers because, she said, food insecurity has different forms and levels. A food bank saying its need went up 50% could actually just involve 10 families.

“We want to get some data that really shows severity like, ‘There are 21,000 kids with food insecurity, but the ones most dire are probably 5,000.’ You want to tell people the truth.”

In Aurora, the need for assistance from food banks has skyrocketed, Esquivel of the Salvation Army Aurora Corps told The Denver Gazette.

Its food bank has seen an increase in the number of people donating and offering assistance, but the need far outweighs the amount of assistance, Esquivel said.

In the 2024 fiscal year, Salvation Army Aurora served about 36,000 people.

Its team saw a 94% increase in the number of people needing food in the last two weeks of October. It is now seeing a 110% increase, Esquivel said.

The organization has already had to tap into its December funding to meet the need, which has not been this high since the COVID pandemic, he said.

Of the influx of people in need, almost half are new to the food bank – either never having come before or not having come since the COVID era, he said.

“I wish I could tell you its one thing but I think it’s a plethora of issues,” Esquivel said. “(About) 45% are brand new people who haven’t come to us before. In many cases, people have returned three, four years after and the last time they were served was (during the) COVID era.”

People are helping Salvation Army Aurora and other food pantries, officials said. The Aurora Police Department, the fire department and city staff are also doing their part.

Every two weeks, the Salvation Army sends a report to Arapahoe County and gets some financial assistance via an emergency grant from the county.

Despite that, Esquivel said, “The rate at which we’ve been experiencing the need, donations have not been enough.”

Moore said the response of the community to food drives has been good.

“People are doing it. It’s innate in us to help each other. It’s in our DNA. But the thing is to keep it up,” Moore said. “You need to remember the people who were crying because they didn’t have anything to eat. We can’t have a short memory about this.”

Denver Gazette reporter Kyla Pearce contributed to this report.