Budget cuts threaten Youth Mental Health Corps for rural students

In rural Colorado, a single school counselor can face impossible odds. With limited staff, students in crisis are at high risk of slipping through the cracks, and having their emotional, social, and academic needs unmet.

At Moffat Schools in the San Luis Valley, school counselor Sarah DeLeon knows those challenges firsthand. “School counselors can be a difficult position to fill given our rural location,” she said.

DeLeon serves 114 students, many of whom face significant challenges outside of school. Nearly 20% of students qualify for McKinney-Vento services for unhoused youth, and many face poverty or other forms of instability at home that affect their daily lives and learning.

Even with support from San Luis Valley Behavioral Health and a part-time counselor, many students remain at risk of not receiving the help they need.

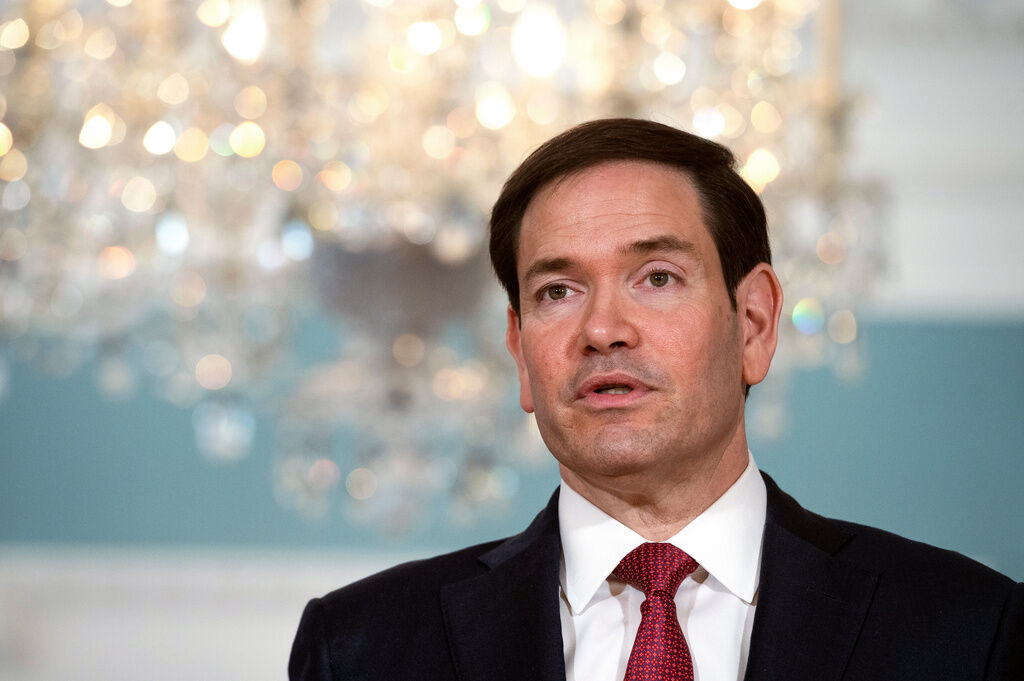

The Youth Mental Health Corps (YMHC), launched after the pandemic by Lt. Gov. Dianne Primavera and John Kelly, executive director of Serve Colorado, the state’s AmeriCorps program, was created to help schools like Moffat address urgent needs.

The program places trained Corps members in schools and community centers across Colorado to provide near-peer support, expand counseling capacity, and build a pipeline of future behavioral health professionals.

At Moffat, that role is filled by Karen Gamez, a Corps member who recently started working directly alongside DeLeon. The position offers a bridge between students and the formal counseling system while also preparing Gamez and others for future careers in the field.

“ Long-term, I hope my work is impactful enough where Sarah can get the help she needs and students feel comfortable coming to me,” Gamez said.

Training and mentorship are central to the Corps’ design. Members complete coursework in Youth Mental Health First Aid, trauma-informed care, crisis intervention, therapeutic communication, and case management while receiving direct supervision from school staff.

“They get training and credentials offered through the Colorado Community College system, besides their on-the-ground experience working with students,” Primavera said. “Their credentials range from micro-credentials all the way up to master’s level. And they’re also supported under the mentorship of the (counselors) they are working under.”

To prepare members for the unique challenges of rural placements, the program also offers community-building opportunities. Megan Strauss, founder of the Alpine Achievers Initiative, which supports AmeriCorps placements in rural schools, described a week-long residential retreat that kicks off each service year.

“It’s focused on building community within the cohort to increase their own resiliency” Strauss said. “It offers equity and belonging trainings and orientation to the communities where they will be serving.”

Once in schools, Corps members work closely with multiple partners to ensure students receive comprehensive support.

“They collaborate with counseling staff, teachers, law enforcement, and community coalitions to identify at-risk students and coordinate wraparound support,” DeLeon said.

“Our agency support services committee is a consortium of folks from all over the San Luis Valley that ensures our families get everything from food and clothing to emergency shelter and tutoring. These supports are fundamental to our ability to be successful both here at the school level, but more importantly, our outcomes for the students that come out of here.”

Still, funding remains a persistent challenge. Federal AmeriCorps budget cuts issued in April reduced the first-year YMHC cohort from 145 members to just 80 in Year 2, leaving fewer Corps members in schools and limiting the mental health support available to students. “We’ve had a cut in our budget, which means we can’t provide as many services. We can’t provide as many professionals,” Primavera said.

Nate Gonzales, principal at Ortega Middle School in Alamosa, underscored the same point: “It’s always a struggle to get paraprofessionals… Having that extra person in the building, it’s very valuable, especially in a rural area.

“It’s very valuable to our kids to have consistent people… a lot of our kids are being raised by grandparents and foster parents,” Gonzales said. “So having that consistency that they might not have at home is very valuable.”

Added Strauss, “In a rural community where the whole staff might be 20 people, adding that one person is massive. To lose 15 full-time members … it hurts the students more than anything.”

To maintain continuity in her school, DeLeon has kept Moffat’s Corps position funded through a combination of layered grants and partnerships.

“Had I not received this AmeriCorps member to support my role, I’m not certain that I would be able to choose to serve in this local school capacity because my role needs the support in order for the work to be sustainable,” she said. “Without Karen here (through AmeriCorps) the simple matter would be our students would not receive social emotional learning supports whatsoever.”

Efforts like DeLeon’s help sustain a program that is building a broader pipeline of mental health professionals across the state. Primavera said nearly two-thirds of Corps members plan to remain in Colorado, with most pursuing advanced education in behavioral health fields.

“The fact that we have this pipeline already established and such a need … 1 in 3 Colorado high school students report persistent sadness or hopelessness … that’s a huge boost for our pipeline for mental health workers,” she said.

According to AmeriCorps data, Youth Mental Health Corps members deliver up to $34 in community value for every $1 invested. By providing early interventions in schools, the program helps licensed behavioral health specialists practice at full scope, reducing emergency costs while improving attendance and graduation rates.

Since the budget cuts, the program and participating Colorado schools have had to adjust their approach in order to ensure services continue despite limited resources.

“It’s really sad. Instead of decreasing the program, we should be expanding it,” Primavera said. “We have more people wanting to join the program than we have spots for them. We’d like to see the program reach all corners of the state with sustainable funding.”