Colorado justices toy with test for reviewing extreme sentences for unconstitutionality

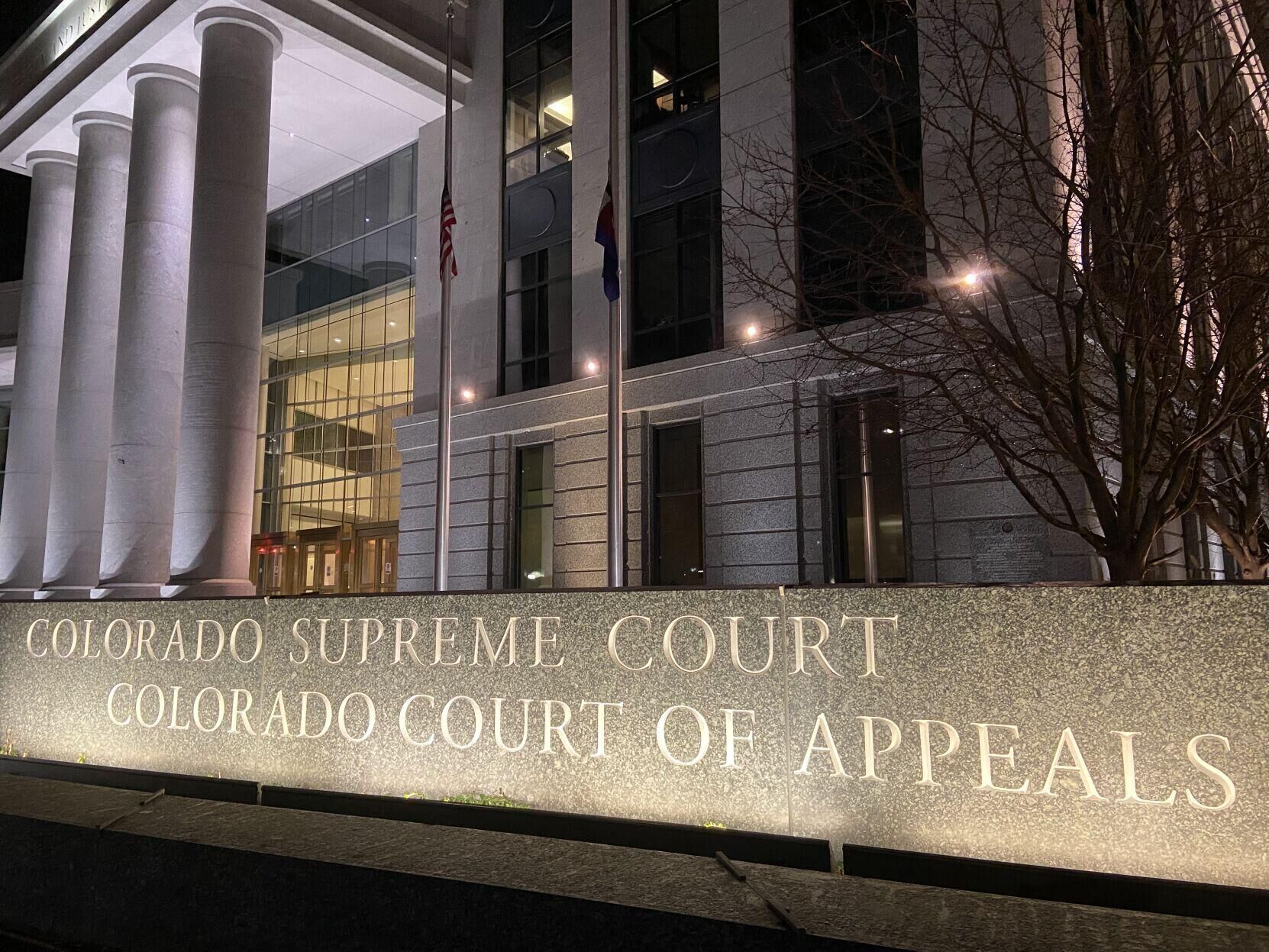

The Colorado Supreme Court heard arguments on Monday about whether a woman’s 29-year prison sentence for causing a fatal drunk driving accident was constitutionally excessive, but also considered tinkering with the procedure for how judges approach claims of “gross disproportionality” in sentencing.

The Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment means sentences cannot be grossly disproportionate to the crime. When judges in Colorado examine the constitutionality of a sentence, they first consider whether the offense was grave and serious, then assess the harshness of the punishment. The Supreme Court has recognized that if an offense is “per se” grave and serious — meaning serious in all scenarios — and the sentence is within the authorized limits, it is “nearly impervious” to a challenge.

During oral arguments, however, the state’s justices wondered if defendant Kari Mobley Kennedy was correct to advocate for abolition of the per se grave and serious designation.

That label “is a Colorado thing. This is not a United States Supreme Court concept,” said Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. “This is something that Colorado came up with at some point along the way.”

“This argument that what does this per se ‘shortcut’ really get us? …. Should we maybe jettison it?” wondered Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez.

Yet, Justice Brian D. Boatright pointed out that Kennedy’s case did not squarely raise the issue of altering Colorado’s special process for reviewing the constitutionality of sentences.

If it did, “it would draw a lot of attention, would you agree?” he asked Kennedy’s lawyer.

Kennedy was driving extremely intoxicated in Larimer County when she hit another car head-on and killed Benjamin Shettsline. She pleaded guilty to DUI-based vehicular homicide and vehicular assault, with the prosecution and defense agreeing that Kennedy’s maximum sentence for both counts would be 33 years in prison.

Chief Judge Susan Blanco sentenced Kennedy to 24 years for vehicular homicide and five years for vehicular assault, citing Kennedy’s prior drunk driving offenses, her repeated bond violations and the danger she presented to the community. Kennedy then petitioned for Blanco to reconsider, alleging the sentence was unconstitutional.

Blanco responded that vehicular homicide caused by intoxication is a per se grave and serious offense because it involves a person’s death, and she further concluded the 24-year sentence imposed for the crime was not grossly disproportionate.

A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals partly agreed. It parted ways with Blanco’s characterization of Kennedy’s vehicular homicide charge, believing it was “not one of those rare crimes” that is always grave and serious.

“By way of example, imagine an individual who exceeds the prescribed dosage of a prescription medication and then crashes a golf cart into an infirm, elderly man thereby causing his death,” wrote Judge Terry Fox. “Now imagine another individual with a history of drinking and driving who intentionally drinks to the point of severe intoxication before driving his car and fatally running over that same man.”

She elaborated that the different ways of committing the same crime weighed against deeming it grave and serious in all circumstances. The panel concluded, however, Kennedy’s particular offense was extremely serious and the sentence Blanco imposed was constitutional.

Both sides appealed to the Supreme Court. Senior Assistant Attorney General Melissa D. Allen advocated for deeming Kennedy’s offense grave and serious across the board.

“Every single time, someone dies,” she told the court.

Justice Melissa Hart noted that careless driving resulting in death is not a felony offense, and someone who happens to cause a fatal drunk driving accident may have tried to take steps to be responsible.

“What if someone, not this situation — absolutely not this situation — but what if someone had two glasses of wine,” she said. “Waited for an hour, thought they were OK, but was at .08” blood alcohol content?

“Doesn’t matter,” said Allen, because Colorado’s DUI vehicular homicide law is “strict liability,” meaning someone’s mental state is irrelevant to whether they are guilty.

In response to a question from Justice William W. Hood III, Allen conceded she could not recall another strict liability crime that courts have deemed per se grave and serious.

“The only difference between a DUI and a vehicular homicide DUI is that in the latter case, you get in an accident and someone dies. But the conduct is the same,” observed Samour.

Kennedy’s lawyer argued the absence of any intent to commit the offense and the fact that the legislature treats careless driving resulting in death more leniently suggested Kennedy’s crime was not grave and serious across the board. Multiple justices countered that Kennedy’s actions, specifically, justified her prison sentence.

“It’s not just the death,” interjected Márquez. “It’s the choice to drink. The choice to get, while intoxicated, behind the wheel of a car. And that resulting in death.”

“What was wrong with saying that ‘Given you are unable to control this particular aspect of your conduct, given that you killed someone and severely injured another person, given that you were driving with an extraordinarily high BAC, I’m sentencing you at the upper end of what you agreed to in your plea agreement?’” added Hart. “Where’s the gross disproportionality in that?”

In discussing whether to abolish the designation of per se grave and serious offenses, Allen conceded it was “a weird concept anyway.” But she noted it was even odder in Kennedy’s case, where the same judge who just sentenced her also was tasked with reviewing the constitutionality of that sentence.

Allen said the concept of per se grave and serious makes more sense under Colorado’s “three-strikes law,” where prior offenses are used to lengthen a subsequent sentence.

“SCOTUS doesn’t do this. We’ve created, arguably, a little bit of a cottage industry around what constitutes per se,” said Hood.

Allen responded that the benefit to designating certain offenses as always grave and serious is that it reduces the time for judges to analyze whether a sentence is so extreme as to violate the Eighth Amendment.

“One issue with per se analysis is the sentence is gonna be upheld as constitutional in virtually every case when we get there,” said Justice Richard L. Gabriel. “I’m not sure what the harm would be to say, ‘You know what? The defendant has rights here. Make the court go through the analysis to say this is not grossly disproportionate.'”

The case is People v. Kennedy.