Denver board held behind-the-scenes talks on Marrero’s contract

The Denver school board may have run afoul of Colorado’s open meetings law by channeling discussions about Superintendent Alex Marrero’s contract extension through the district’s attorney and a secret, two-member committee, according to experts.

Among those raising concerns is Steve Zansberg, a First Amendment attorney who represents The Denver Gazette and several other media organizations.

The Denver school board has long faced criticism for operating behind closed doors, which board members have brushed aside, insisting they operate transparently.

In extending Marrero’s contract, the board sidestepped open debate in favor of private channels that shielded Marrero — and the district’s elected leaders — from public scrutiny.

“They play all these games to avoid public scrutiny,” said David Lane, a civil rights attorney representing former McAuliffe International Principal Kurt Dennis, who is suing the district.

Zansberg, the First Amendment lawyer, said the board’s methods amounted to evading Colorado’s open meetings law, which requires the public’s business to be openly conducted.

State law, in fact, permits public entities to receive legal advice in an executive session.

The school board didn’t do that.

A person familiar with the March 20 executive session purportedly to receive legal advice on Marrero’s contract described it as a “high-level” meeting focused on procedure, rather than details.

A planned April 2 executive session to discuss Marrero’s contract was scrapped without a motion after public backlash. Nine parents and former educators spoke during public comment on the early extension — none in favor.

The Denver Public Schools (DPS) board of education never rescheduled the executive session and therefore did not discuss proposed amendment changes to Marrero’s contract.

Instead, Board President Carrie Olson put the contract on the agenda for a vote.

On May 1, the board voted, 5-2, in favor of giving Marrero a two-year extension on his contract, which included significant changes that included a 5-2 supermajority requirement to remove the superintendent without cause and a 90-day notice, up from 60 days previously required.

Marrero’s contract is set to expire next June.

Directors John Youngquist and Kimberlee Sia — both elected two years ago in a sweep that saw the incumbents lose their seats — voted against the early extension.

Both have complained about the lack of transparency in the process.

“I still don’t know how the decisions were made,” Sia told The Denver Gazette.

‘Done in compliance’

Before the vote, Youngquist complained about being excluded from the process — a statement with which Director Michelle Quattlebaum took issue.

Quattlebaum and Vice President Marlene De La Rosa both served on the ad hoc committee.

“Every board member had an opportunity to add their own comments, make their own recommendations and strike any recommendations that they did not agree with,” Quattlebaum said before the May 1 vote.

At the time, it was unclear when board members would have had the opportunity to do so.

District officials maintain the process complied with state law.

“Dr. Marrero’s contract extension process was done in compliance with the Colorado Sunshine Law,” Bill Good, a district spokesperson, said in an email.

The Denver Gazette has learned that, behind the scenes, board members routed their feedback on Marrero’s contract through the district’s counsel and the two-member committee — a process the board never acknowledged publicly until June.

Quattlebaum said directors provided input to the district’s legal counsel.

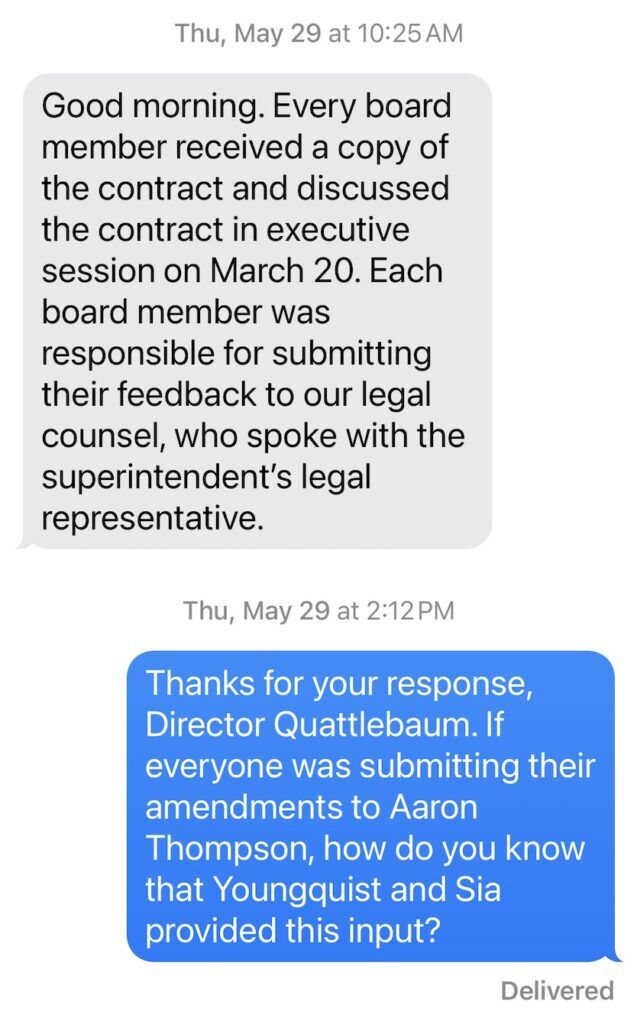

“Every board member received a copy of the contract and discussed the contract in executive session on March 20,” Quattlebaum wrote. “Each board member was responsible for submitting their feedback to our legal counsel, who spoke with the superintendent’s legal representative.”

As DPS’ general counsel, Aaron Thompson reports to Marrero, not the board of education. The school board does not have its own legal counsel.

Although Quattlebaum previously described a process that involved the full board, she did not disclose the two-member committee on which she served.

That wasn’t publicly known until later.

While the board debated new guardrails for its committees in a policy workshop, Director Xóchitl Gaytán let slip an off-the-cuff remark about the committee.

The committee, Gaytán publicly disclosed, was “formed of just two board members to move forward the superintendent’s contract extension work.” Gaytán identified Quattlebaum and De La Rosa as the two committee members.

“So, would that be defined as committee under this policy,” Gaytán asked.

De La Rosa responded, “That’s the way I would read it.”

Marcus Johnson, the district’s senior attorney and policy director, also agreed, saying, “My answer is yes.”

‘Evade a quorum’

Gaytán’s description went unchallenged by her board colleagues and the attorneys in the room.

While no one disputed Gaytán’s account at the time, board members have since offered conflicting accounts of what happened behind the scenes.

Gaytán said she submitted her comments on Marrero’s contract to the committee — specifically to Quattlebaum. Quattlebaum, however, told The Denver Gazette she did not and that feedback was directed to the district’s attorney.

Whether the board provided feedback on proposed contract changes to the committee or directly to Thompson, both methods violated Colorado law, legal experts said.

“There are different ways to evade the CORA requirement for having a public meeting,” Zansberg said.

Zansberg added: “It’s clear that regardless the type of method, it was used to evade a quorum requirement.”

In other words, whether through a daisy chain or what’s called a “hub-and-spoke,” the effect was the same — to get around state law, which requires that when a quorum of board members (four for DPS) discusses public business, the meeting must be public and properly noticed.

A “daisy chain” happens when public officials deliberately sidestep open meeting laws by discussing public matters one-on-one or in small groups. The goal is to circumvent the threshold for a quorum — the minimum number of members required for a public body, like a school board, to legally conduct business.

This is what the Douglas County Board of Education did in 2022, when four members discussed firing former superintendent Corey Wise in a series of one-on-one and private meetings. (State Rep. Bob Marshall, D-Highlands Ranch, later sued the district and won.)

And legislators at the state Capitol changed the law to allow themselves to discuss bills and public policy via email or text message without it being subject to the open meetings law. Those communications could be available through an open records request — assuming the public knows who was in the conversation and when it took place.

But those changes only apply to the Colorado General Assembly, not to any other political subdivision in the state, such as the Denver Public Schools or a county commission.

In a “hub-and-spoke” arrangement, board members pass their proposed contract language through the district’s attorney, instead of debating it in public. Zansberg said what board members did does not amount to legal advice — which is permissible — but policy drafting, which state law requires be done openly.

Attorneys told The Denver Gazette that attorney-client privilege exemption from the Colorado Open Records Act (CORA) is reserved for seeking and receiving legal advice — not for hammering out the terms of a contract. Using legal counsel as a go-between to negotiate or draft policy, they said, places the board outside the bounds of the law.

“A communication is not an attorney-client privilege because an attorney is there,” said Tom Kelley, a First Amendment attorney.

Kelley added: “It does sound like this was a successful effort to shield a lot of discussion from the public that should have been done in public.”

‘Out of public view’

Olson defended the process.

She suggested the committee acted appropriately because “no one provided information” to them. But she also struggled to provide any meaningful insight into how and why the committee was formed.

The Denver Gazette asked Olson — at her request — nearly two dozen written questions about the committee including: its purpose; when and how frequently committee members met; whether agendas, minutes or recordings were kept and if members briefed other directors between meetings.

The newspaper also inquired as to whether or not Olson believed the committee was subject to state law, the legal rational for the secret committee and whether any recommendations were made.

Olson declined to respond.

Instead, she referred the questions to district officials.

Good, the DPS spokesperson who answers to Marrero, said, “all district policies” were followed.

In Colorado, committees such as the one created to oversee Marrero’s contract, are required to conduct their work in a properly noticed public meeting.

Zansberg, the First Amendment attorney, said that if three or more members — in this case Olson, Quattlebaum and De La Rosa — discussed forming the special committee, then the matter should have been voted on by a quorum of the board.

“This must be done in public,” Zansberg said.

De La Rosa deflected questions, saying she would have to check her email and then did not respond. Quattlebaum insisted the group was mislabeled as a “committee” — a designation that carries legal obligations — but refused to explain what she believed it should have been called.

There is no evidence that the committee’s formation was publicly discussed nor that it held properly noticed, public meetings.

“It seems like the process that was used was intended to keep the conversation out of public view,” Youngquist said.

This would not be the first time the Denver school board has faced accusations of sidestepping state law to conduct public business out of view.

Two years ago, a Denver district court ruled the board violated the state’s open meetings law by privately debating the return of school resource officers after the East High School shooting and ordered the audio released.

Four current members, including Olson, were present in that session.

The board also has restricted public comment, a forum often critical of its actions. Under a new policy, speakers must sign up before the agenda is even posted.

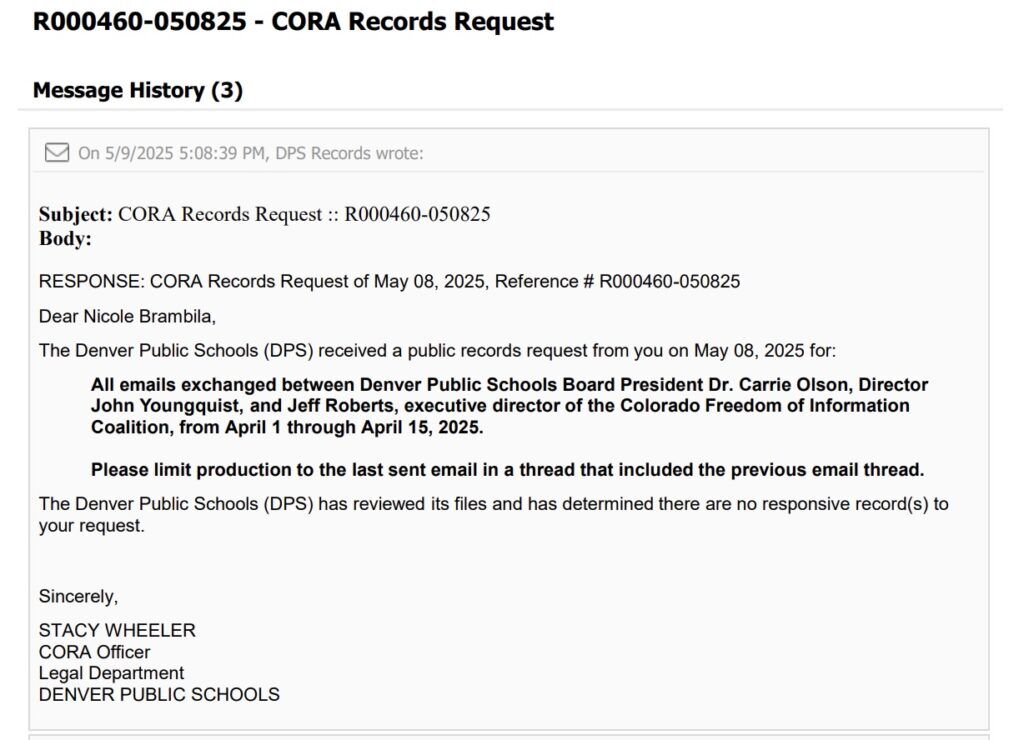

The district likewise has a history of denying records requests with “no responsive records,” only to later produce them. That happened when an email from Olson’s personal account only surfaced after a second request — and again, when officials withheld records on student pat downs until requesters used the district’s jargon. Those pat downs, conducted at East, were among the practices scrutinized after the shooting that injured two administrators.

“This is not an isolated incident,” Zansberg has said about the board’s actions. “I think it’s irrefutable that there is a pattern of conduct that the district has not abided by the state’s transparency laws.”

Board members shruged off the complaints.

“We are transparent,” Quattlebaum said. “This has been one of the most transparent boards that I can think of.”

‘Done as a board’

It is unclear how often board members receive training on Colorado’s open meetings and records laws.

What is clear is that most of the directors are not new to the job — a majority have served at least four years (three were sworn in two years ago) and Olson, now in her eighth year, has already completed a term as board president.

Given her experience, Olson would have known that a “daisy chain meeting” violates state law, experts said.

And if there were any doubt, Jeff Roberts, executive director of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition, told her as much.

The coalition promotes the freedom of the press and open access to government.

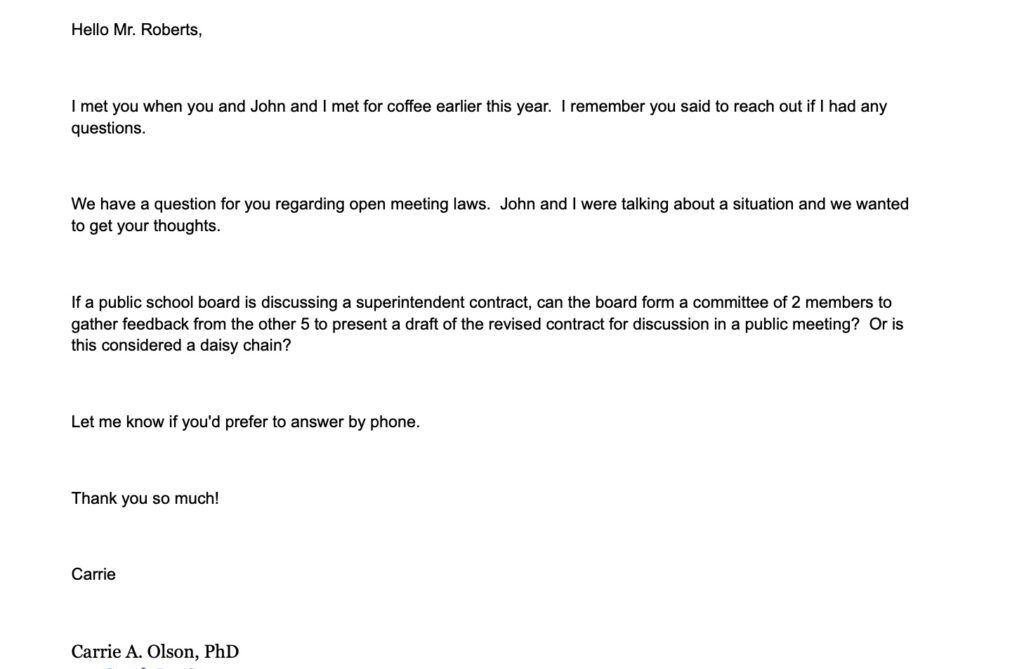

About three weeks before the May 1 vote on Marrero’s contract extension, Olson sent an email — from her private account — to Roberts, an expert on Colorado’s open meeting laws, asking if a two-member committee would violate state law.

“If a public school board is discussing a superintendent contract, can the board form a committee of 2 members to gather feedback from the other 5 to present a draft of the revised contract for discussion in a public meeting? Or is this considered a daisy chain,” Olson asked Roberts in an April 8 email obtained under CORA.

Her answer came 14 hours later.

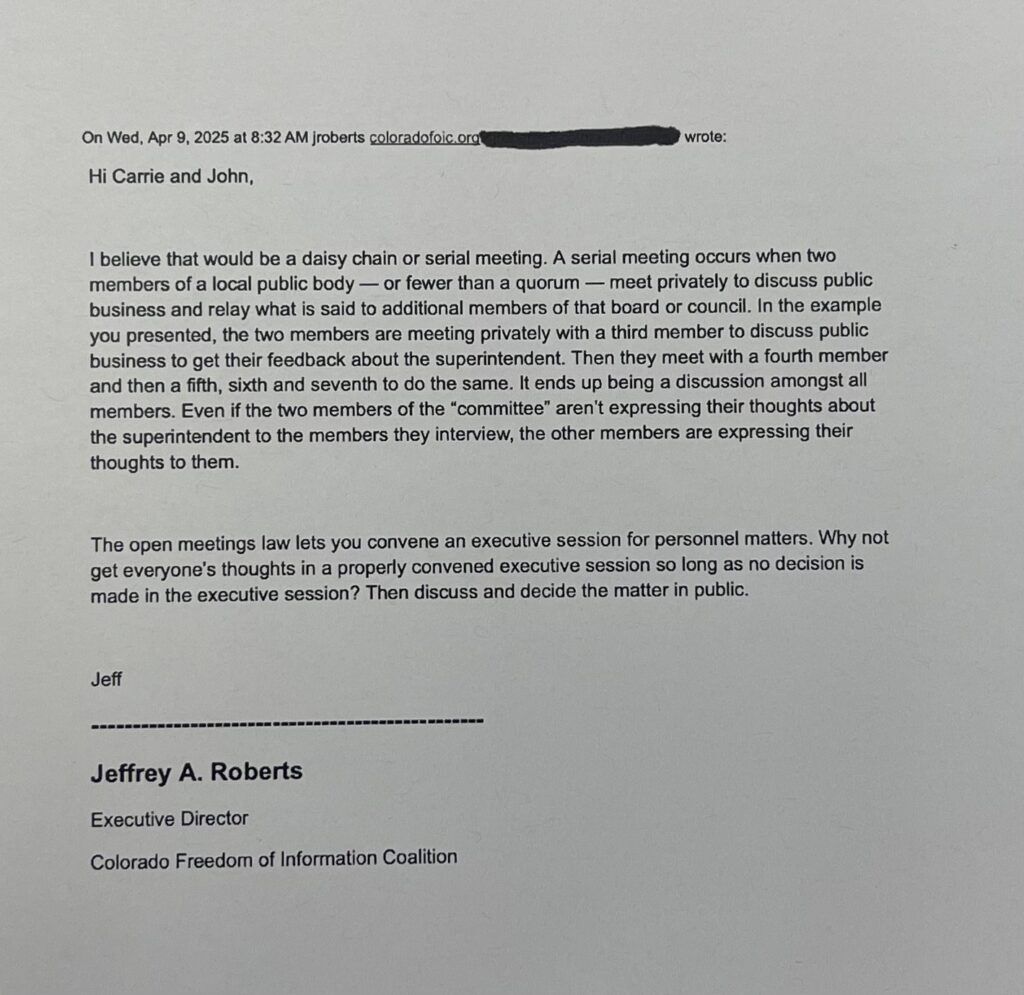

“I believe that would be a daisy chain or serial meeting,” Roberts wrote back.

Roberts recommended — a week after the board had tried and failed — to convene an executive session for personnel matters.

“Why not get everyone’s thoughts in a properly convened executive session so long as no decision is made in the executive session,” Roberts said. “Then discuss and decide the matter in public.”

That’s how it’s supposed to be done, said Theresa Peña.

Peña previously served on the DPS board of education for eight years, twice as president.

While on the board, Peña went through the contract process with former superintendents Michael Bennet and Tom Boasberg.

“We never set up a committee,” Peña said. “It’s ways always done as a board.”