‘I can help open doors’: Colorado Supreme Court justice, judges speak about obligation to mentor

Members of the Colorado Supreme Court, Court of Appeals and the trial courts spoke to an audience of lawyers last week about the benefits of seeking a mentor in the legal profession and about their feelings of obligation to help other attorneys.

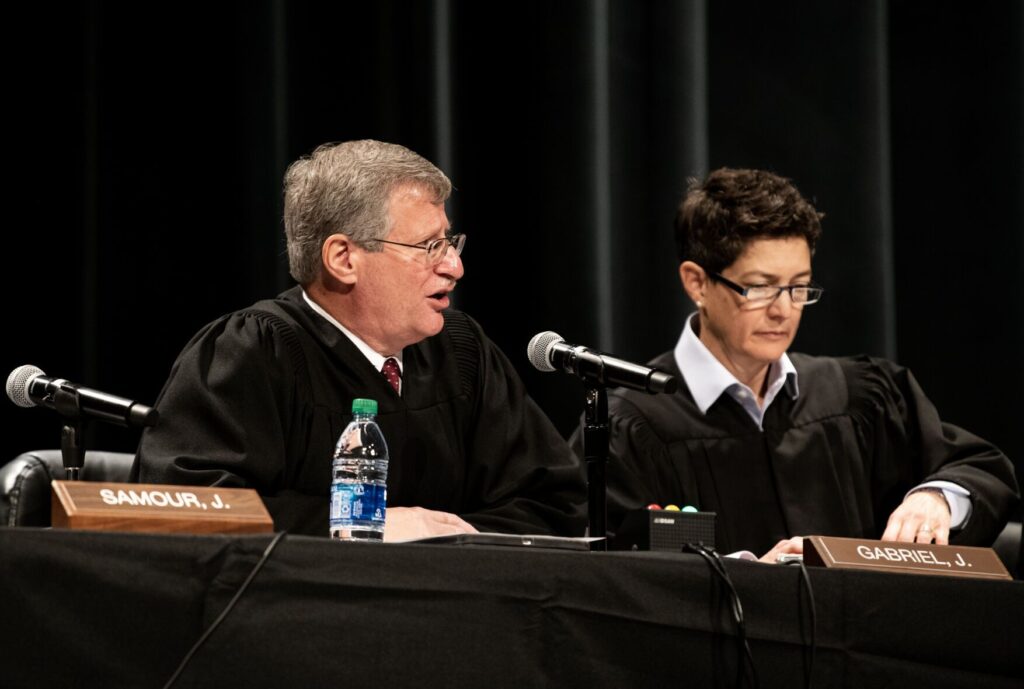

“I can help open doors, particularly now with the title I have in front of my name. And I have an obligation to do that,” said Justice Richard L. Gabriel.

The Aug. 27 virtual event, sponsored by the law firm Wheeler Trigg O’Donnell and the Colorado Women’s Bar Association, explored the aspects of being an attorney that benefit the most from mentorship. Denver District Court Judge Heidi L. Kutcher said she tends to seek out multiple perspectives when she has an ethical question.

“I would go to my mentors and talk about ‘this has come up for me while I’m sitting on the bench. How would you deal with this?’” she said. “‘I know this feels wrong to me and I may not know why,’ and I’ll talk to someone who will help me figure out why it feels wrong to me.”

“Having a safe place to say, ’I feel like an imposter. I have no idea what other law students are talking about when they say X,’ especially for first-generation law students,” added Judge Sueanna P. Johnson of the Court of Appeals. “That ability to go, ‘I spoke with my mentor on Sunday and I go into the office and I’m feeling confident so I can talk with the partner on Monday,’ that’s just invaluable to have.”

Gabriel listed other actions mentors can take, like making introductions, promoting what their mentee is doing and providing guidance about how to practice law correctly and ethically. They can also share credit with their mentees for successes and take the blame for failures.

“I mean no disrespect to anybody here. Law school provides foundational tools, but it can’t possibly address all of the things that are necessary to succeed in the practice of law,” he said.

A 2019 analysis of mentorship from the National Academy of Sciences noted that historically in the United States, “mentoring has carried a connotation of a mostly unidirectional relationship between a more senior individual using life experience and acquired knowledge to guide the development, growth, or entry of the mentee into future life stages or career paths.”

However, mentoring has evolved into a more reciprocal arrangement.

Retired Denver County Court Judge Alfred C. Harrell said he treated his mentoring relationships as “quid pro quo.”

“All of the mentees that I’ve had over the years, they treat me as an equal. I learn as much from them as they learn from me,” he said.

Gabriel described his experience as an attorney for the late pop star Michael Jackson, who was being sued for copyright infringement. Gabriel, a professional musician himself, recalled his mentor told the other lawyers that “Rich has to try this case. He knows it better than any of us.”

“That’s a wonderful example of mentoring. Here’s a senior partner in a law firm who chose to step aside,” said Gabriel, “to do what he thought was right for the client.”

He added that while law firms had formal mentoring programs at one point, those have “gone by the wayside.” Now, the Colorado Supreme Court has established a voluntary mentoring initiative, complete with a handbook outlining the elements of a mentoring relationship.

“I had no role models and I made stupid mistakes because of my lack of role models,” said Gabriel. He elaborated that mentoring historically tended to benefit White men in the legal profession, and he felt obligated to counteract that trend.

“When traditional barriers come down, equity, diversity and inclusivity in our profession go up. Especially for those like myself — I am privileged, I am a White man — I can help that,” he said. “I think I have an obligation to stand up and be an ally and open doors for folks who don’t have the advantages I have. But that’s the way to do it and be transparent about what you’re doing.”