Denver judge exceeded his authority in ‘several ways’ in juvenile defendant’s case, state Supreme Court says

'While the trial court has significant discretion regarding the presentation of evidence and the application of the rules of evidence, there are limits,' wrote the justices

The Colorado Supreme Court ordered a Denver judge on Friday to eliminate several of the restrictions he unreasonably placed on a juvenile defendant’s ability to argue that he should not be tried as an adult for his offenses.

Lawyers for Clayshjon Eugene Clark-Collins sought the Supreme Court’s intervention after District Court Judge Eric M. Johnson indicated he largely did not want to hear live testimony about the 11 factors in state law for “reverse transferring” the case to juvenile court. Johnson also required the defense to otherwise submit its written evidence 30 days beforehand and limited the hearing — which can take multiple days or even a week — to half of one day.

In an unsigned Aug. 8 order, the justices agreed Johnson had exceeded his authority “in several ways.”

“While the trial court has significant discretion regarding the presentation of evidence and the application of the rules of evidence, there are limits,” the Supreme Court wrote.

In February 2024, prosecutors charged Clark-Collins with 15 counts related to aggravated robbery and weapons possession. Clark-Collins was a few months shy of 18 at the time. The defense requested a reverse transfer hearing to address whether his case should be moved from district court, where he faced up to 32 years in prison if convicted, to juvenile court, where Clark-Collins would face less punitive consequences.

The defense requested a three-day reverse transfer hearing. Johnson interrupted to say he would set it for half a day instead. Ticking through the 11 factors in state law that judges must consider before granting a transfer to juvenile court, Johnson said Clark-Collins’ criminal history and the seriousness of the charges would be self-evident, and he did not need a “deep dive” into Clark-Collins’ past.

“What’s left really can get done in a day,” he added.

Johnson then issued a written order announcing that he was combining the reverse transfer hearing with a preliminary hearing, which requires prosecutors to demonstrate probable cause exists to bring the case to trial. Johnson wrote that the “vast majority of the evidence” he would consider for the reverse transfer hearing would take the form of documents.

Moreover, all evidence able to be put in writing “will be submitted to the Court 30 days prior to the hearing,” he wrote.

Clark-Collins’ lawyers asked Johnson to reconsider, pointing out multiple problems with the proposed procedure. He declined to alter the hearing.

“Oral testimony gives the court a chance to correct any assumptions or confusion or misunderstandings that are contained in reports,” public defender Efosa Akenzua argued to the Supreme Court in June.

Moreover, added Clark-Collins’ second attorney, Priscilla Gartner, one of the factors to consider in transferring to juvenile court is the nature of the offense — evidence of which coming from the defense could make the prosecution’s job easier in the adjacent probable cause hearing.

Assistant Attorney General Lily E. Nierenberg, representing Johnson, argued his conditions were appropriate and aimed at efficiency.

“What the defense is asking for in this case is no boundaries, effectively turning these hearings into a trial,” she said.

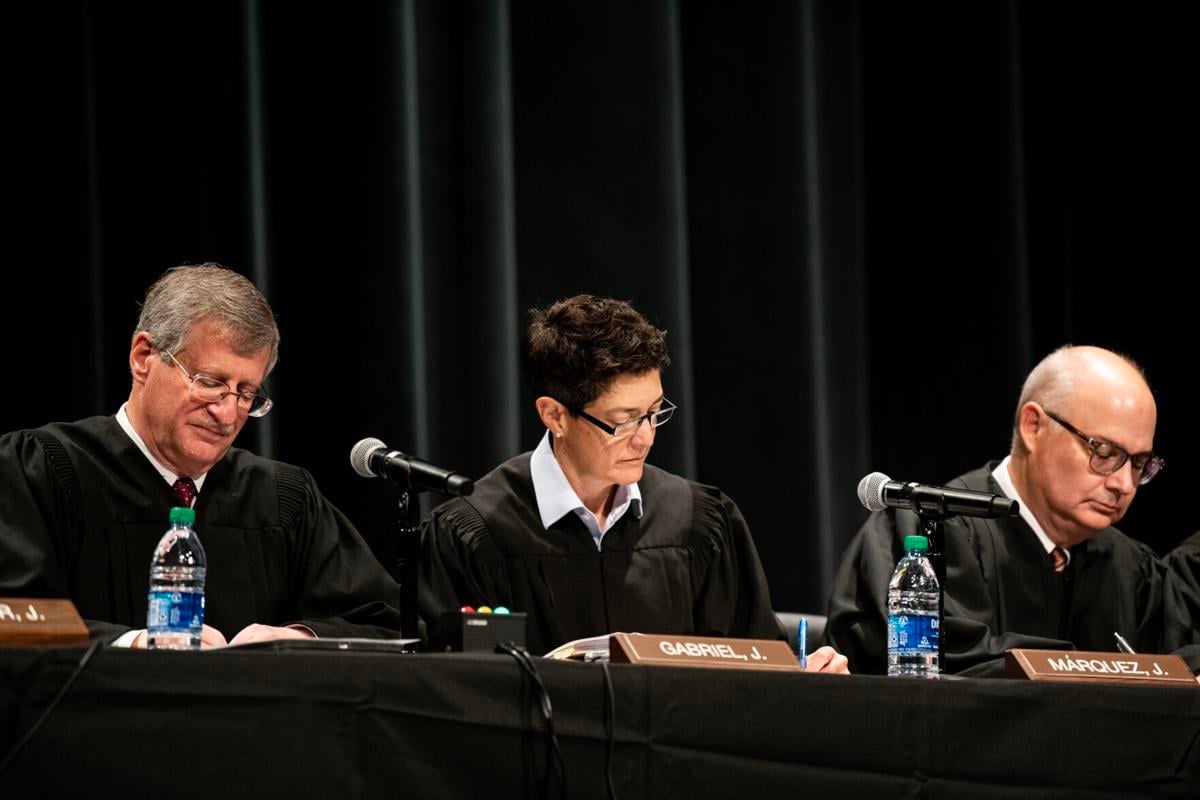

“The flip side,” interjected Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez, “is you would appear to have us draw a line that lets the court exercise unlimited discretion in constraining or defining in advance how the hearing should be run. Is that true?”

Justice Richard L. Gabriel wondered what law or rule empowered Johnson to require the defense to share its evidence 30 days in advance.

“I’m having trouble seeing what the authority is for that,” he said.

Finally, Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr., a former trial judge, had “several concerns” with how Johnson approached the hearing, including how Johnson was supposed to determine witness credibility if he expected to take the bulk of evidence in written form, without cross-examination.

“It feels to me like the judge is essentially eliminating most of the hearing and limiting it to just the bare minimum,” Samour said.

In its order, the Supreme Court noted judges “cannot require” juvenile defendants to submit all evidence in advance and to put experts’ conclusions into writing. There is also “no authority” requiring juveniles to make witness disclosures 30 days beforehand.

As for Johnson’s limitation on testimony about Clark-Collins’ upbringing, he took an “overly narrow interpretation of what is relevant” in assessing Clark-Collins’ maturity, the court wrote.

The justices ordered Johnson to adjust his restrictions accordingly and then hold the hearing.

The case is People v. Clark-Collins.