Federal judge partially sides with Catholic health clinic on Colorado’s ‘abortion reversal’ ban

A federal judge on Friday permanently blocked Colorado from enforcing against a Catholic health clinic the portion of a 2023 law that prevents medical professionals from offering “abortion reversal” treatment to pregnant patients.

Bella Health and Wellness initially succeeded in obtaining an injunction against Senate Bill 190, arguing its providers were compelled by their faith to assist pregnant patients who had changed their mind after beginning the process of medicated abortion. Consequently, SB 190 unconstitutionally burdened their religious exercise.

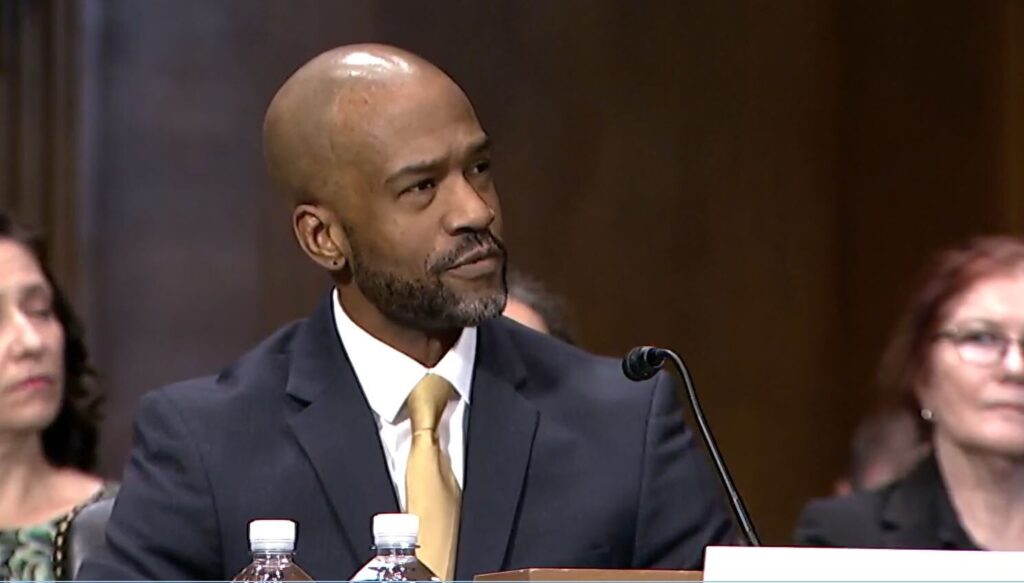

U.S. District Court Judge Daniel D. Domenico noted in an Aug. 1 order that the evidence produced since the 2023 preliminary injunction “largely confirms” his original understanding. Adding he would “generally have no trouble giving the state” discretion to regulate treatment whose efficacy is questionable, that did not apply when closely scrutinizing a law’s effect on religious exercise.

Although the “clinical efficacy of abortion pill reversal remains debatable, nobody has been injured by the treatment and a number of women have successfully given birth after receiving it,” he wrote. “The Defendants have thus failed to show that they have a compelling interest in regulating this practice, and Plaintiffs’ motion must therefore be granted to the extent it seeks a permanent injunction allowing them to continue offering the treatment.”

However, Domenico, a first-term appointee of President Donald Trump, sided with the state in Bella Health’s challenge to other portions of SB 190 that address abortion reversal treatment as a “deceptive trade practice.”

“Colorado should never have tried to stop Bella from helping pregnant women who want to choose life for their babies,” said Rebekah Ricketts, senior counsel at the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, which represented the Englewood-based clinic and its founders. “This ruling ensures that pregnant women in Colorado will not be denied this compassionate care or be forced to have abortions against their will.”

The Alliance Defending Freedom, which represented nurse practitioner plaintiff Chelsea M. Mynyk, characterized Domenico’s order as “striking down” or “permanently blocking a state law.” However, Domenico himself stressed that was not the case, and cited a high-profile U.S. Supreme Court decision from June that sharply restricted judges’ authority to grant relief to non-parties.

“I therefore emphasize that any injunction in this case covers enforcement actions against the Plaintiffs, not the law itself,” he wrote.

When seeking a medication abortion, a pregnant patient typically takes the drug mifepristone, followed by a dose of misoprostol. Although a pregnancy may survive even in the absence of the follow-up dose, administration of progesterone could increase the chances of maintaining the pregnancy.

The evidence in either direction, however, is not ironclad. Joseph Vernon Turner, a senior lecturer at the University of New England in New South Wales, wrote last year that “there is a lack of quality evidence concerning any benefit of progesterone treatment,” but disputed that there are “safety concerns for prescribing progesterone.”

A recent review of medication abortion reversal studies published in the BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health journal also cautioned “there is insufficient evidence to recommend progesterone treatment to reverse the effects of mifepristone.”

The plaintiffs, in moving to end the lawsuit in their favor, wrote that 11 babies had been born to Bella Health’s patients since it sued in April 2023. Their lawyers contended they were “engaged in a religious exercise that the government seeks to punish.”

The government countered that Colorado lawmakers were within their rights to declare abortion reversal unprofessional conduct — unless the state’s boards of pharmacy, nursing and medicine all decided it was a generally accepted practice — due to the lack of evidence about its efficacy.

Domenico concluded the de facto ban on treatment was not “generally applicable” because it targeted a specific use of a specific drug that was part of the plaintiffs’ “religious calling.” Meanwhile, Colorado did not prohibit the use of progesterone in other medical contexts.

Notwithstanding the scientific dispute over the treatment, “Plaintiffs are right that Colorado’s ‘under-inclusivity of regulation in a closely related context further undermines the State’s asserted interest in protecting patients’,” he wrote.

Domenico also noted the regulatory boards indicated they would evaluate on a “case-by-case basis” whether abortion reversal treatment was unprofessional conduct, providing the state discretion in how to enforce the law.

“Overall, it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that Plaintiffs’ use of progesterone is not being regulated neutrally — it is being singled out,” Domenico concluded.

While he found the ban on treatment was neither narrow nor served a compelling government interest to justify the infringement on the plaintiffs’ religious exercise, Domenico sided with Colorado on the remaining challenge to sections of the law addressing deceptive advertising by abortion reversal providers.

Since the preliminary injunction was issued, “it has become clear that Plaintiffs should no longer reasonably fear enforcement of these sections,” Domenico explained. “For one, nearly two years of litigation have elapsed without the Attorney General initiating any investigation of Plaintiffs for a potential violation.”

If that changed, he added, the plaintiffs could file a new motion.

The case is Bella Health and Wellness et al. v. Weiser et al.