Federal judge declines to reconsider rejection of challenge to Colorado Springs municipal elections

A federal judge on Tuesday stood by his previous decision that a collection of civic and voting rights groups lacked the ability to challenge the timing of Colorado Springs’ municipal elections.

Last summer, U.S. District Court Judge S. Kato Crews did not address whether the city’s practice of holding local elections in odd-numbered years amounted to a discriminatory practice under the Voting Rights Act. Instead, he leaned on a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision to find the plaintiff groups had not suffered an injury simply because they spent money on local voter education initiatives.

“The City has held its municipal elections in April as early as 1873. The Plaintiff organizations were founded multiple decades (and sometimes over 100 years) later,” Crews wrote, “meaning the City conducted April elections for numerous years before these organizations existed, and it has continued to hold April elections well after.”

In reaching his conclusion, Crews, an appointee of Joe Biden, accused the plaintiffs of attempting a “fabrication” of their standing to sue, and of making “reckless and untrue” arguments.

Quickly, the plaintiffs asked Crews to reconsider both his conclusion and his rhetoric.

“Plaintiffs take their ethical obligations seriously and did not intend to mislead the Court,” their lawyers wrote.

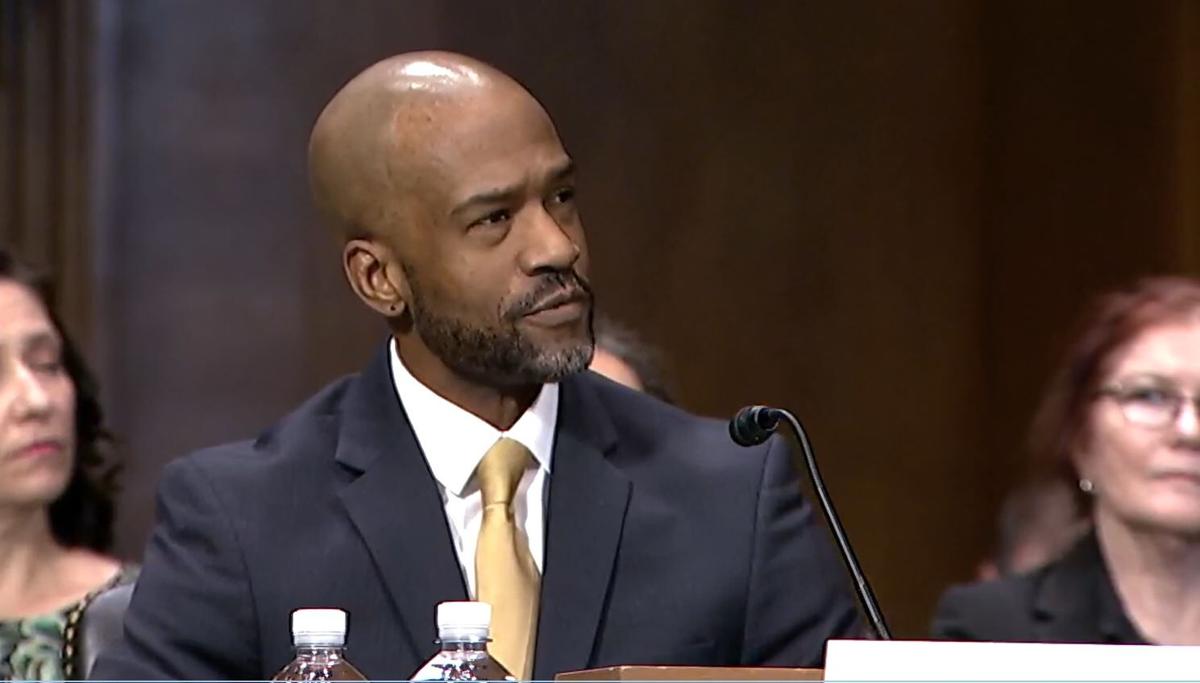

Yemi Mobolade takes photos with his supporters Tuesday, May 16, 2023, during an election watch party at the COS City Hub in Colorado Springs, Colo. Mobolade defeated Wayne Williams in the Colorado Springs mayoral runoff to become the first elected black mayor of the city. (The Gazette, Christian Murdock)

Christian Murdock

Around the beginning of 2022, Harvard’s Election Law Clinic contacted multiple groups about suing the city — Citizens Project, Colorado Latinos Vote, the League of Women Voters of the Pikes Peak Region and the Black/Latino Leadership Coalition.

They alleged their voter education and get-out-the-vote activities required “additional effort” and diversion of resources in April of odd-numbered years that could be avoided if the city aligned its own election with the state’s November election.

The plaintiffs cited statistics showing Black and Hispanic participation in the city’s April elections was roughly half that of White voters, but the gap substantially narrowed during November elections. The lawsuit sought to require Colorado Springs to move its elections to November because of the allegedly discriminatory effect of April elections on voters of color.

“Plaintiffs do not contend that minority voters face scheduling hurdles in spring elections that white voters do not confront,” the city’s lawyers responded. “Plaintiffs instead contend that there is only one right election date — specifically, the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November — and every other day is wrong.”

Crews, in his original order, largely relied on a less-than-one-month-old Supreme Court decision, Food and Drug Administration v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine. In that case, a group of medical associations opposed to abortion challenged the government’s longstanding approval of the medication abortion drug mifepristone, even though they did not prescribe or dispense the drug themselves.

An organization “cannot spend its way into standing simply by expending money to gather information and advocate against the defendant’s action. An organization cannot manufacture its own standing in that way,” wrote Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh.

The room bustles on Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024, during the Republican election watch party at Boot Barn Hall in northern Colorado Springs. (The Gazette, Arthur H. Trickett-Wile)

Arthur H. Trickett-Wile, The Gazette

The plaintiffs, in asking Crews to reconsider, argued they never had the opportunity to specifically address the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine decision. Further, they contended they must divert money from other initiatives in order to engage voters about the city’s springtime election — which was not the same as the medical associations’ spending to oppose mifepristone.

Colorado Springs reiterated the plaintiffs’ position was neither legally nor logically sound.

“Plaintiffs want all governments (federal, state, and local) to conduct their affairs (i.e., elections) at (concurrent) times when it is most convenient and inexpensive for Plaintiffs to engage the public,” responded attorneys for the city. “If standing arose from that desire, anyone could spend $2 on speech and sue because $1 would suffice if government only conducted its affairs in some other way.”

Addressing the request for reconsideration, Crews defended his original ruling by noting he has an obligation to address whether plaintiffs have standing to sue. Moreover, the recent Supreme Court decision “did not alter or reverse” the other precedent he relied upon, he wrote in the March 25 order.

Crews did, however, soften his prior accusations against the plaintiffs’ lawyers. He thanked them for clarifying the arguments he deemed “reckless and untrue,” now saying he “understands Plaintiffs take their ethical obligations seriously and the air is now cleared on that issue.” Crews also noted his characterization of the plaintiffs having “manufactured” their standing “attributes no bad faith on Plaintiffs’ part.”

The case is Citizens Project et al. v. City of Colorado Springs et al.