Colorado Supreme Court weighs meaning of ‘personal identifying information’

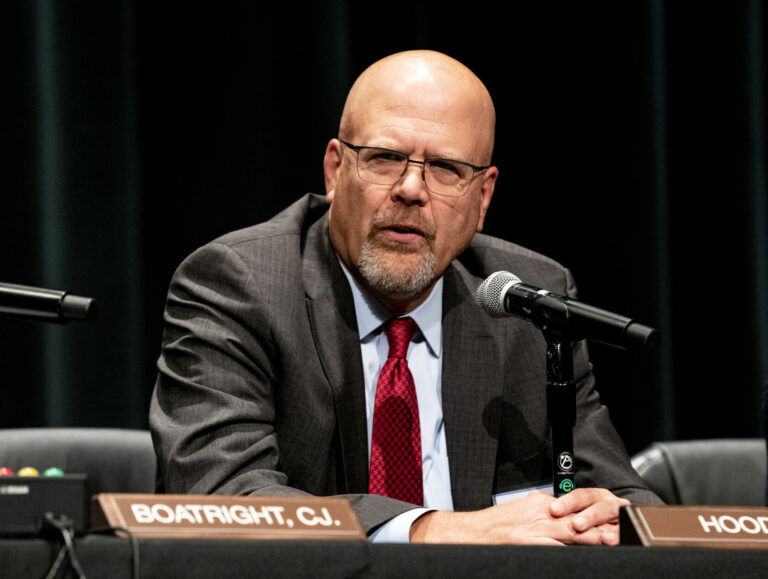

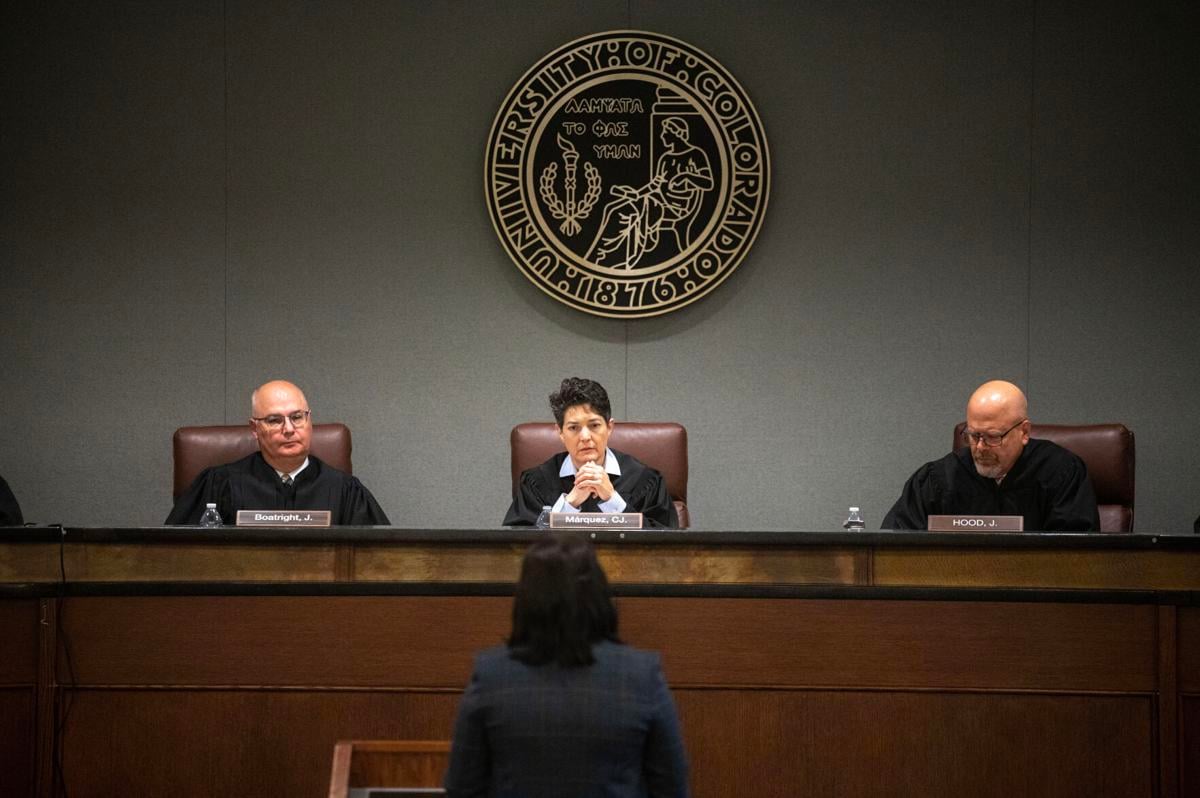

(From left) Colorado Supreme Court Justice Brian D. Boatright, Chief Justice Monica M. M á rquez and Justice William W. Hood III listen to arguments from Assistant Attorney General Caitlin E. Grant during the People v. Rodriguez-Morelos case as part of Courts in the Community at the Wolf Law building at University of Colorado Boulder on Thursday, Oct. 24, 2024. The semi-annual event entails the Colorado Supreme Court hearing arguments before an audience of students throughout the state. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Stephen Swofford Denver Gazette

Members of the Colorado Supreme Court pondered on Thursday whether “personal identifying information” under the state’s identity theft law only encompasses humans, or if businesses can have personal identifying information, too.

The government argued legislators enacted the identity theft law in 2006 to deter fraudulent conduct, and the meaning of personal identifying information should be read broadly.

However, during oral arguments, Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez recited the specific items lawmakers listed as personal identifying information, which include birthdates, social security numbers, biometric data and driver licenses.

“Those are all very human kinds of identifiers,” she said. “Help me understand what we can glean from the list there to say this pertains more broadly to corporations.”

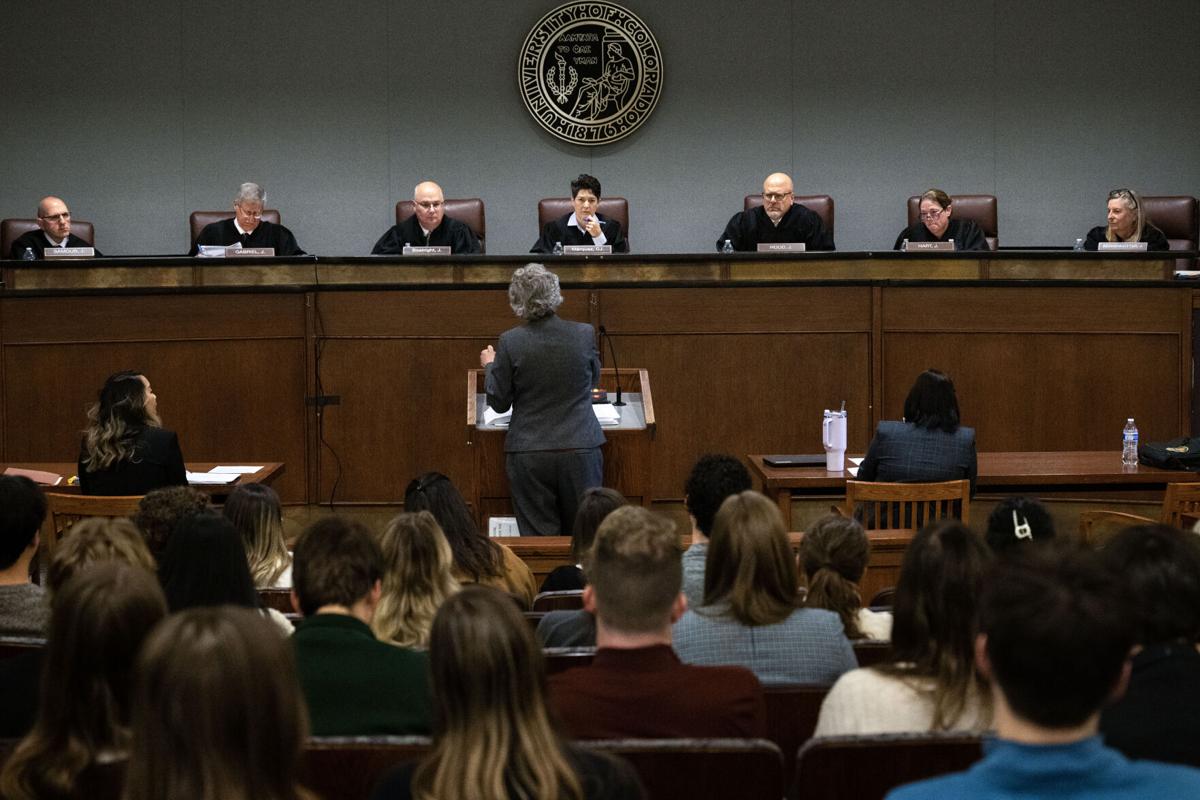

The Colorado Supreme Court hears a rebuttal from First Assistant Attorney General Wendy J. Ritz during arguments for People v. Rodriguez-Morelos as part of Courts in the Community at the Wolf Law building at University of Colorado Boulder on Thursday, Oct. 24, 2024. The semi-annual event entails the Colorado Supreme Court hearing arguments before an audience of students throughout the state. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Stephen Swofford Denver Gazette

The Colorado Supreme Court hears a rebuttal from First Assistant Attorney General Wendy J. Ritz during arguments for People v. Rodriguez-Morelos as part of Courts in the Community at the Wolf Law building at University of Colorado Boulder on Thursday, Oct. 24, 2024. The semi-annual event entails the Colorado Supreme Court hearing arguments before an audience of students throughout the state. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

The Colorado Attorney General’s Office acknowledged the circumstances surrounding Jesus Rodriguez-Morelos’ identity theft conviction were uncommon and the legal dispute was narrow. But prosecutors believed the Court of Appeals, in overturning the conviction, read the law incorrectly.

An Arapahoe County jury found Rodriguez-Morelos guilty of theft, identity theft and criminal impersonation. Rodriguez-Morelos legitimately volunteered with a nonprofit helping migrant workers, but he falsely held himself out as the group’s “director of education” and offered unauthorized classes to become a nursing assistant.

Most students were Spanish speaking and some were undocumented. None of the people who testified at trial had received jobs as nursing assistants.

The most serious charge, identity theft, could have been proven through Rodriguez-Morelos’ use of the nonprofit’s financial identifying information at the end of the course or appropriating the nonprofit’s name at the outset. The latter theory would fall under the law’s prohibition on using the personal identifying information “of another” without permission. Personal identifying information, in turn, encompasses details that identify “a specific individual.”

The Court of Appeals concluded neither form of identity theft was proven in Rodriguez-Morelos’ case because, among other things, the nonprofit was not a “specific individual.”

“In other words, if the prosecution charges a defendant with identity theft for using personal identifying information, but the thing used does not fit within the definition of that term, then the defendant has not committed the crime,” wrote Judge Steve Bernard.

The government appealed, citing testimony from 2006 when the legislature changed the law. At the time, a prosecutor told lawmakers the crime of identity theft was meant to encompass victims who were a “living person, they could be a dead person, or definitely a business entity.”

“I do acknowledge, in layman’s terms, a ‘specific individual’ could mean ‘human being,'” Assistant Attorney General Caitlin E. Grant told the justices at oral argument. But the appellate court “forgot the context of the identity theft statute and what it’s trying to protect.”

First Assistant Attorney General Wendy J. Ritz, left, listens to an argument from Deputy State Public Defender Kira L. Suyeishi as they argue their sides before the Colorado Supreme Court during the People v. Rodriguez-Morelos case as part of Courts in the Community at the Wolf Law building at University of Colorado Boulder on Thursday, Oct. 24, 2024. The semi-annual event entails the Colorado Supreme Court hearing arguments before an audience of students throughout the state. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Stephen Swofford Denver Gazette

First Assistant Attorney General Wendy J. Ritz, left, listens to an argument from Deputy State Public Defender Kira L. Suyeishi as they argue their sides before the Colorado Supreme Court during the People v. Rodriguez-Morelos case as part of Courts in the Community at the Wolf Law building at University of Colorado Boulder on Thursday, Oct. 24, 2024. The semi-annual event entails the Colorado Supreme Court hearing arguments before an audience of students throughout the state. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Some members of the court wondered if Rodriguez-Morelos’ inability to be convicted of identity theft would make his case the exception, rather than the rule.

“Other than this case, wouldn’t business entities generally be covered in every instance by the financial identifying information protection?” asked Justice Melissa Hart.

“And P.S., the defendant was also convicted of criminal impersonation,” added Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter.

Public defender Kira L. Suyeishi, representing Rodriguez-Morelos, conceded the legislature could have more clearly referred to humans, rather than “individuals,” but the word choice clearly excluded nonhuman entities.

Does it make sense, asked Berkenkotter, that she could steal financial identifying information from the American Cancer Society and be charged with identity theft, “but I have no exposure if I steal the name ‘American Cancer Society’ and go around fundraising? That to me is a little problematic.”

“You’re not stealing money from the American Cancer Society directly. You’re stealing money from the people door-to-door. So, they would be victims,” replied Suyeishi. She added the American Cancer Society could potentially sue the perpetrator in lieu of an identity theft charge.

Hart observed that in reality, it would be difficult to pull off such a fundraising scheme without providing fictitious financial documentation to the victims to make things seem legitimate, which would squarely fall within the identity theft law.

“If I look at personal identifying information in this statute,” she said, “they are all things that are identifiers for human beings. Not so much identifiers for business.”

The arguments took place at the University of Colorado’s law school as part of the judicial branch’s “Courts in the Community” program.

The case is People v. Rodriguez-Morelos.