Dead cattle and high blood pressure: Wolf depredation takes toll on Colorado ranchers

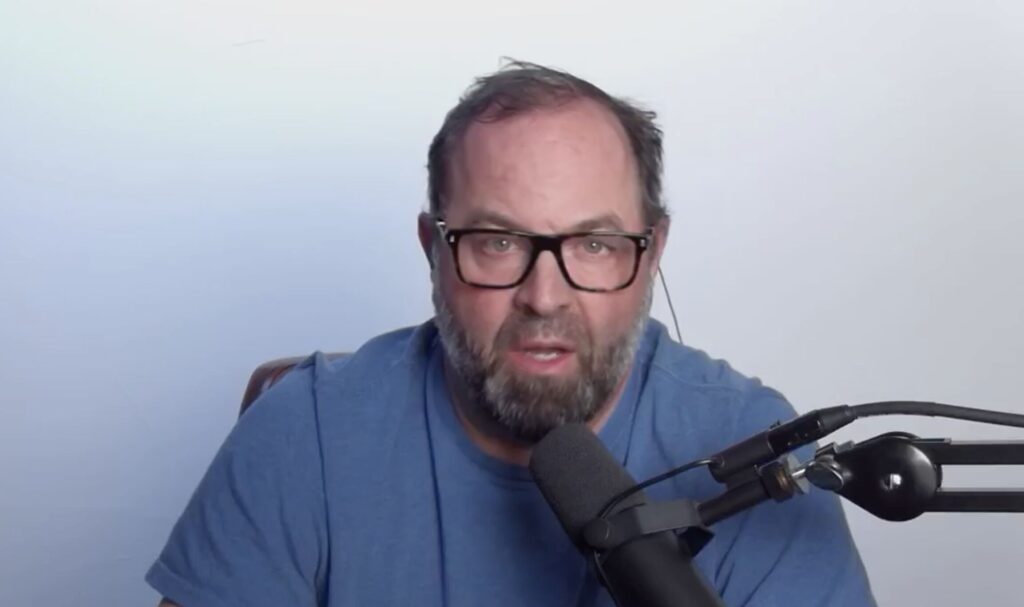

In the middle of an interview with a group of ranchers last week, Middle Park rancher Doug Bruchez excused himself to retrieve the results of medical tests.

His family’s ranching operation was the first in the area to report wolf depredation, and he has been stressing out since the apex predator — reintroduced in Colorado last December, the culmination of a ballot measure that urban voters approved four years ago — killed a calf in April.

At only 39, Bruchez is showing symptoms normally associated with old age or with a serious illness, which he believes is from the stress and the lack of sleep he has been suffering in the last several months.

“We had a wolf meeting last Friday, and it got so bad I had to go outside to try and get some fresh air, and my hands were shaking so bad I could not figure out what was going on,” Bruchez told The Denver Gazette. “I took my resting heart rate. (It) was 130 and my blood pressure was 162 over 112.”

A wolf is seen near herds of Angus cattle in a thermal video by a Middle Park Stockgrowers Association's range rider.

Courtesy of Middle Park Stockgrowers Association

Bruchez said he has never suffered from high blood pressure in his entire life and, when it happened again, he got an EKG.

“What the doctor told me is that I am about to blow a gasket,” Bruchez said. “I’m so stressed out and so sleep deprived, and after examining me, the doctor is even willing to write a letter to whoever wants to see what is happening up here.”

The release of the gray wolves in Grand County last December stoked political tensions over the most ambitious reintroduction effort in the country in almost three decades. At the state Capitol, wildlife officials faced intense grilling from legislators over what the latter described as communication failures. Meanwhile, livestock associations warned that the relationship between ranchers and the state has deteriorated to the point that it is now threatening wildlife officers’ access to private lands for other conservation efforts.

To Bruchez and his family, however, the issue is much more personal, his medical worries illustrating the stress and anxiety ranchers face half a year since wildlife officials released 10 wolves into Colorado’s Western Slope. While the debate is raging in committee hearings, through public relations campaigns and on the pages of Colorado’s newspapers, Bruchez and the other ranchers in the area must contend with the fact the top predators are now settling in to make the valleys, lakes and peaks of the north-central Rocky Mountains their new home.

‘Killing them for fun’

Bruchez, who graduated from Colorado State University in 2007, is a first-generation rancher in Grand County. He had started in 2011, but he is part of an agricultural family going back six generations.

Bruchez runs the Grand County operation with his brother Paul and father Art.

Bruchez said his family’s operation was the first in the area to experience a wolf depredation on a calf on April 2, a kill confirmed by Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

The state is tracking gray wolf depredation, and the data shows that, since April 2, eight livestock kills have been confirmed in Grand County alone. The page lists a total of 23 cattle or calves, three dogs, and three sheep killed statewide since December 19, 2021. The kills included depredation by wolves that migrated to Colorado from Wyoming several years ago.

“I am confident that we have had several others that we just didn’t know what we were looking at,” Bruchez said. “I thought a wolf kill was going to be blood and guts and eaten and everything else. And the first one — if there was not perfectly definitive wolf tracks in the snow where this dead calf was — I probably would’ve not even known that that was a wolf kill.”

Bruchez said that both ranchers and wildlife officials are not yet accustomed to seeing wolf kills and don’t quite know how to identify them yet.

“If it wasn’t for the snow and the tracks, that one would’ve probably gone by the wayside, too, because they’re not eating them,” said Bruchez. “It appears to me, when you see some of these, that they’re just killing them for fun.”

Rob Edward, a founding member and board member of the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project, told The Denver Gazette that livestock lost to wolf depredation is “extremely minimal.”

“The fact is that depredations on livestock happen all the time,” Edward said. “Yes, it hurts individual ranchers, the ones that suffer those depredations. We totally get it, and that’s why we’re working with Colorado Parks and Wildlife and other nonprofit organizations to help ensure that the best that can be done at the time is done to help minimize future depredations.”

Cattle and other farm animals, he said, die in the hands of other predators or to weather or to rustling.

“And so the kinds of losses that the wolf population that Colorado will ultimately have, the ranchers will incur, are still going to be extremely minimal in the scheme of things,” he said. “What we do know is that in those places where wolves and livestock share common ground, so let’s say any wolf occupied counties in Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, the depredation rate on livestock annually is less than one-tenth of 1%.”

Gray wolves had killed some 800 domesticated animals across 10 states in 2022, including Colorado, according to a previous Associated Press review of depredation data from state and federal agencies. While the losses can impact individual ranchers, it’s a fraction of the industry at large — only about 0.002% of herds in the affected states, according to the analysis.

To supporters, the wolves play an important role in ecosystem balance.

That dominant view of wolves restoring the pre-extirpation ecosystem arose out of the concept called “trophic cascade,” which occurs, biologists say, when apex predators indirectly benefit plants by changing the abundance of herbivores or their foraging behavior, causing plant biomass, for example, to increase.

The return of wolves to Yellowstone in 1995, this theory goes, triggered such a cascade.

The predators, some postulate, changed the behavior of the elk population, which, in turn, allowed willows to recover from intense browsing. That provided beavers with an abundant food source, and, as the beavers returned, they built dams and began to change the habitat. Another study offered a similar conclusion, finding increases in the height, stem diameter and stem establishment, and canopy cover of deciduous woody plants in riparian areas following the wolves’ introduction.

That is, the theory claims, the wolves halted — or reversed — the decimation of vegetation as a result of intense grazing.

New research from Colorado State University is challenging that widely accepted narrative that the reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone National Park in the mid-1990s resulted in restoring the habitat that degraded after the apex predators were removed roughly a century ago. The CSU researchers, drawing from a 20-year study, concluded the changes that occurred in Yellowstone in the intervening decades — after the absence of wolves, cougars and grizzly bears ultimately led to overgrazing of willows by the elk population — produced a new, stable, elk–grassland ecosystem, but it was not because of the wolves.

That dominant view of trophic cascade was one of the animating arguments in favor of Proposition 114, the 2020 citizen initiative that mandated wolf reintroduction in Colorado.

That year, supporters told voters that gray wolves “perform important ecological functions that impact other plants and animals. Without them, deer and elk can overgraze sensitive habitats such as riverbanks, leading to declines in ecosystem health.”

Edward insisted that living next door to wolves is now simply the new reality for ranchers, who must adapt.

“With anything else in business, some people suffer losses and businesses suffer losses at one time and others don’t,” he said. “Some businesses get hit with golf, ball size, hail and have to replace all their windshields for their delivery trucks, and the place down the street just didn’t get hit.”

He added: “This is the reality of doing business, and we understand that we’re asking for people to adapt to a big change. We totally understand that. But wolves are not the end of the world.”

Wolf No. 2309 and Wolf No. 2312

Bruchez and the other ranchers who spoke to The Denver Gazette on May 24 said the problem appears to be a pair of wolves released by wildlife officials somewhere near Heeney, along the Blue River south of Kremmling.

The pair likely has built a den in the mountains on the west side of the Williams Fork valley and are — according to Colorado Parks and Wildlife — believed to be mating.

The pair, identified by the Middle Park Livestock Growers Association as “Wolf No. 2309 and Wolf No. 2312,” came from packs in Oregon known to have depredated on livestock. The association said the animals were responsible for the livestock killings that began in April in the Williams Fork and Colorado River valleys.

Wildlife officials last fall told the legislature’s House Agriculture, Water and Natural Resources Committee they would do everything possible not to bring “problem” wolves to Colorado. In fact, the state of Oregon reported that half of the 10 wolves sent to Colorado came from packs that attacked livestock eight times in 2023 alone. Two of those attacks took place in May of last year, killing one five-week-old calf and injuring two four-to-six-week-old calves.

In its letters to the wildlife agency, the Middle Park Livestock Growers Association said that Colorado’s decision to import wolves from depredating packs violated the reintroduction plan and the implementing regulations.

In response to complaints and demands for lethal control of the depredating wolves, CPW Director Jeff Davis effectively conceded the packs’ depredating history but insisted that the state didn’t do anything wrong.

“While the wolves that were selected for reintroduction may have come from packs that were historically chronically depredating packs, management action was taken in Oregon and in the months leading up to capture prior to translocation to Colorado, the packs were not implicated in depredation,” CPW Director Jeff Davis said in an April 23 letter to the association.

“To continue to state that we brought known problem wolves into the state is a falsehood,” Davis said, adding the state has no immediate plans to remove the two wolves.

The association countered that there is no wiggle room in the requirement to exclude importation of wolves from known depredating packs.

Edward of the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project said the situation was brought about by other states refusing to allow Colorado to take their wolves, as the latter faced a reintroduction deadline.

“That is ultimately the result of the situation we faced trying to get wolves to fulfill the mandate of the law. Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana all steadfastly refused to provide wolves,” Edward said. “So, we had a very small pool of wolves to start with that we could actually draw from. And yet the clock was ticking to meet the letter of the law.”

That problem persists today, and the state is exploring other avenues to get more wolves. Colorado officials anticipate releasing 30 to 50 wolves within the next five years in the campaign to fill in one of the last remaining major gaps in the western U.S. for the species.

The Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho said it is cooperating with Colorado to procure the next tranche of wolves from tribal lands.

Edward did not answer as to which provision should have taken precedence — the deadline for wolves to be on the ground or the prohibition against bringing in depredating animals.

A list of wolf sightings in or near cattle collated by the association claims 15 direct sightings of wolves between April 2 and May 23.

Starting April 30, the Middle Park Livestock Growers Association said it hired a range rider who patrols at night, using thermal night vision equipment. The patrols attempted to haze wolves away from cattle, the association said.

But in a letter dated May 23 to Davis, the association said even that strategy is ineffective at preventing depredation.

“The problem is that the range rider can cover only a limited area, and wolves just move to another ranch,” the association said. “In any event, the May 9th sighting by the range rider of two wolves did not stop the depredation that occurred and was not discovered until May 11th.”

The group included graphic photos of dead cattle and calves in their letters to the state agency.

‘What’s the future? I don’t know’

Conway Farrell’s family moved to Williams Fork some 36 years ago. He was six month old at the time.

“That’s where I was raised,” Farrell told The Denver Gazette. “We moved up there when I was six months old, and they started leasing places up there and that’s where they’ve been since then. My mom grew up in this county. She grew up over north of Kremmling — they all used to ranch around here.”

Now 35, Farrell, his wife Nellie and their three and five-year old children operate about 3,000 heads of cattle on leased ground, some of which runs up to the foot of the east side of the Williams Fork Range, where the pair of wolves suspected in the depredations appear to be denning.

That the wolves are denning — meaning they’re preparing for birth — is the justification wildlife officials gave in deciding against employing lethal means to manage the depredation.

The Farrells are among the three families raising cattle in the area that have been hit hard by the wolves.

So far, Farrell said he has lost three yearlings and three calves. He’s seen the pair of wolves on several occasions, as have others. Thermal night-vision photos and videos and trail cameras have also documented their movements.

“They couldn’t compensate us enough to put us through what they’re putting us through right now,” Farrell said. “Compensation doesn’t mean a thing. When you see the stress on your family, the stress on your marriage, the stress on the cattle — these cattle are so messed up.”

Farrell said that before the wolves showed up, his cattle were calm enough that they could be rounded-up and moved by one man on a horse and a few stock dogs.

“We take pride in our dogs and what we do every day. We go out there with our dogs moving these cattle and we have really good dogs,” Farrell said. “So, with these dogs, usually one guy can go out there with two dogs and move 300 or 400 head of cattle, yearlings, or cows, and do it by yourself.”

“Now, these yearlings, these cows are so stressed out, you can’t even hardly take a dog into the field with them because they all just go different ways,” Farrell added. “They start running after they’ve been chased by the wolves. And now we can’t even hardly use them.”

While livestock producers are supposed to be compensated by the state for wolf predation, ranchers say not only is compensation unpredictable but it also doesn’t begin to cover the full cost of losing a cow, either monetarily or physically.

Farrell argued that losing a breeding cow also destroys the potential of 12 to 15 calves it will produce in her lifetime, and it damages the genetic line of high-altitude-adapted Angus cattle.

“This year, the stress on my parents and the extra workload on my brother — I’m up there jacking around for three or four hours with the CPW and looking for tracks. I ain’t providing the proper animal husbandry to these cattle,” Farrell said. “My brother’s having to come over here and cover for me here. And everybody’s workloads (is) triple what it was before.”

“What’s the future? I don’t know,” Farrell said.