Colorado Supreme Court clarifies when judges must recuse for potential bias

The Colorado Supreme Court clarified on Tuesday that judges must recuse themselves when there is a “sufficiently high” probability an observer will deem them biased in a case, but an El Paso County defendant had not established his trial judge fell into that category.

Khalil Jamandre Sanders is serving 32 years in prison for shooting and injuring the driver of another car during a road rage incident in February 2017 in Colorado Springs. Early in the trial, then-District Court Judge Barbara L. Hughes disclosed she, too, had previously been the victim of a roadside shooting. The defense moved for her to recuse but she declined to do so, asserting she had no stake in the outcome of Sanders’ case.

The Supreme Court concluded judges should recuse whenever the “probability of actual bias is sufficiently high” to undermine a defendant’s right to a fair trial. In Sanders’ case, however, there were too many dissimilarities between his offense and Hughes’ shooting to establish a high risk she was biased.

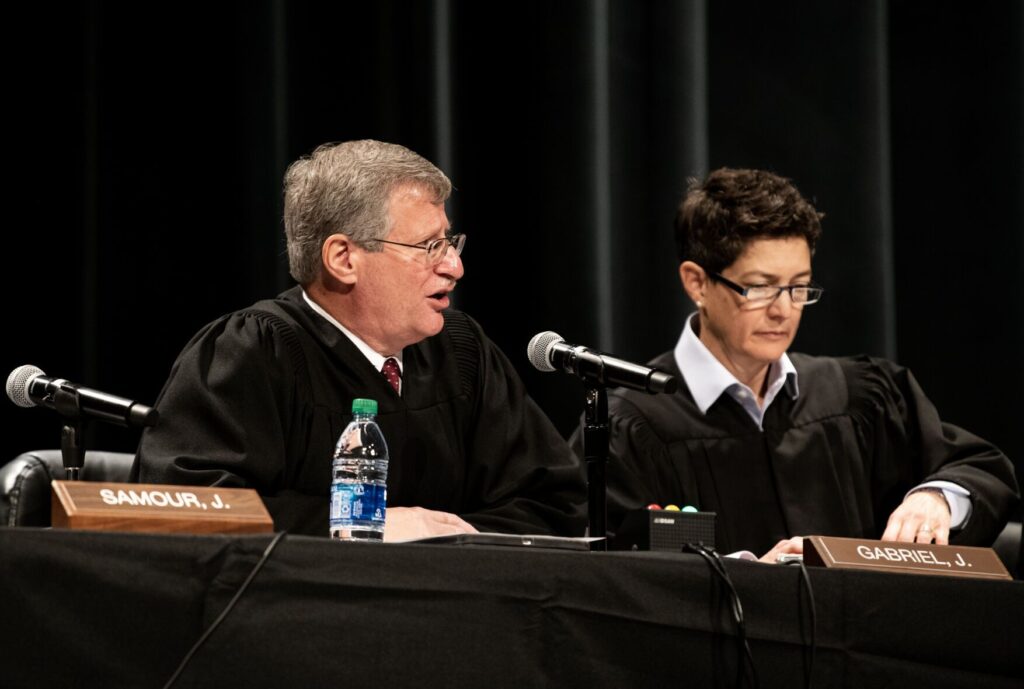

“Judges are not immune from everyday life experiences, and they inevitably bring those experiences, positive or negative, to the bench,” wrote Justice Richard L. Gabriel in the May 28 opinion. “We presume, however, that judges, as professionals, will be able to distinguish their personal lives from their professional obligations.”

During jury selection in Sanders’ trial, in which multiple jurors spoke of their own experiences with road rage, Hughes told the parties she “would be remiss” if she did not disclose something: A few years prior, she was driving in Colorado Springs and saw people fighting in the street. She honked at them and someone shot at her car.

“I heard pop, pop, pop, ping, and it hit the spoiler of my car. I had to duck,” Hughes recalled. “There was a case report, I guess, a police report, but there was never any filing of any charges. There was never any person that was identified as the shooter.”

Sanders’ attorney requested that Hughes recuse herself because she could not “be unprejudiced with respect to the facts of this case based on her own personal experiences.” Hughes declined, asserting she had “no interest in the outcome, no interest in either party,” and her experience was not similar to Sanders’ case.

The Ralph L. Carr Colorado Judicial Center in downtown Denver houses the Colorado Supreme Court and Court of Appeals.

On appeal, Sanders argued Hughes needed to recuse under the constitutional guarantee of due process, under state law, under the rules of criminal procedure and, finally, under the rules of judicial conduct. A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals disagreed with him.

“Due process is satisfied when a judge holds no actual bias,” wrote then-Judge David J. Richman. Even if appearances mattered, “Sanders has not cited, and we have not found, any Colorado precedent holding that an appearance of bias arises whenever a judge presiding over a criminal case has experienced criminal conduct similar to the conduct at issue.”

During oral arguments to the Supreme Court, the Colorado Attorney General’s Office maintained appearances should not matter when challenging a non-recusal. Gabriel, in the court’s opinion, countered that the U.S. Supreme Court’s standard for due process violations is not whether a judge is actually biased, but whether an objective evaluation would deem the risk of bias “too high to be constitutionally tolerable.”

The Supreme Court previously applied that standard to a judge who was himself being criminally investigated while handling cases, a Pennsylvania Supreme Court justice who declined to recuse despite being the former district attorney in the underlying case, and a West Virginia Supreme Court justice who participated in a case where one of the litigants donated millions of dollars to support his election.

FILE PHOTO: News media gather outside the front of the U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, U.S. September 30, 2022. REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque/File Photo

Although Hughes’ experience was somewhat similar to Sanders’ shooting, Gabriel explained Hughes’ incident took place three years earlier, she had handled multiple cases involving weapons since then, and it was not clear whether Hughes’ encounter could be properly classified as road rage.

The state Supreme Court did not address Sanders’ argument that the defense should have been allowed to more fully investigate the details of Hughes’ revelation at trial — at minimum, by looking at the police report Hughes referenced.

“On these facts, we cannot say that the risk of bias was too high to be constitutionally intolerable or that the judge had a direct, personal, substantial, or pecuniary interest in this case. To the contrary, any risk of bias appears to have been merely theoretical,” Gabriel wrote.

The Supreme Court similarly concluded Colorado law, the rules of criminal procedure and the code of judicial conduct did not require Hughes’ recusal, either. Previously, the court ruled that a judge’s appearance of bias may warrant her recusal under the code of conduct, but “only when the judge was actually biased will we question the result.”

The case is Sanders v. People.