Appeals court warns judges, prosecutors to stop dragging feet on victim restitution

Colorado’s second-highest court on Thursday warned that prosecutors should be moving faster to determine the financial restitution owed to crime victims, and that trial judges are empowered to nudge the prosecution along by setting a timeline for calculating the amount owed.

The decision from the Court of Appeals is the latest in a spate of restitution-related challenges ever since the Colorado Supreme Court determined in late 2021 that trial judges and prosecutors generally were failing to follow the procedure in state law for awarding financial restitution to crime victims.

The Feb. 22 ruling from a three-judge appellate panel telegraphed frustration that the Supreme Court’s directive for how restitution should be awarded is still being ignored in some trial courts.

“The current flood of litigation over these issues will largely be avoided,” wrote Judge Timothy J. Schutz, “if the prosecution fulfills its obligation to use diligent efforts to gather and present the information necessary to resolve restitution at the sentencing hearing, coupled with the court’s establishment of case management practices that ensure such obligations are fulfilled.”

Nonetheless, even as the panel found a La Plata County prosecutor ignored his obligation to gather restitution information and blew past a judge’s deadline for disclosing his restitution request, the Court of Appeals upheld the $13,798 in restitution owed by defendant Skylan M. Brassill.

A landmark ruling

In Colorado, when a convicted defendant is required to pay restitution, prosecutors typically must provide the requested amount at sentencing or within 91 days of sentencing. Judges must also impose the restitution amount within 91 days of sentencing. If a judge needs to extend either deadline, they must find good cause exists.

In a major decision, People v. Weeks, the Supreme Court ruled in November 2021 that judges’ typical process of awarding compensation to crime victims did not comply with state law. The justices noted a lackadaisical approach had taken hold in the trial courts that failed to adhere to the clear deadlines and procedural requirements.

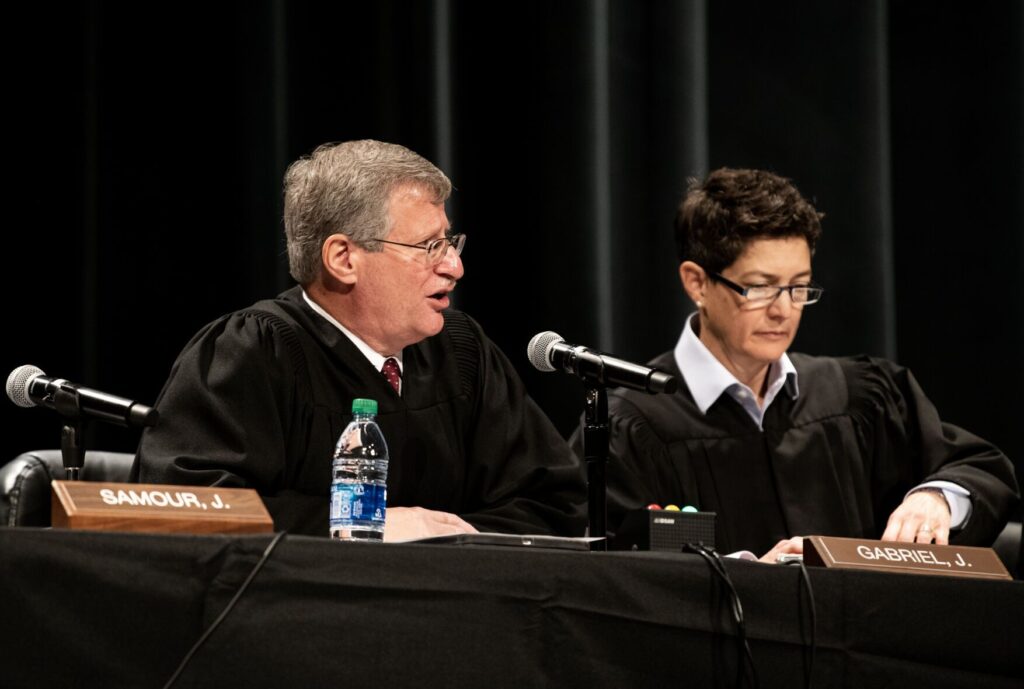

“Imperfect as our restitution statute may be, trial courts have to find a way to adhere to it,” Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. warned in the court’s opinion.

Several decisions out of the Court of Appeals have interpreted prosecutors’ and judges’ compliance with the 91-day deadline. However, Brassill’s appeal focused on the restitution law’s other requirement that prosecutors present their request “prior to” sentencing — with 91 days being afforded only if restitution information “is not available” at that time.

In July 2022, Brassill pleaded guilty to motor vehicle-related offenses he committed eight months earlier. There were three victims owed restitution: the owner of a damaged fence, the owner of a damaged motorcycle and the Colorado Department of Transportation.

At Brassill’s sentencing, Deputy District Attorney Brad Neagos said he did not “have a figure on” restitution yet.

“Why don’t we have any information?” responded District Court Judge Suzanne F. Carlson. “I think we need to start understanding why we don’t have this sort of information when we go to sentencing.”

“I don’t have a good excuse,” Neagos admitted.

Carlson then ordered Neagos to submit his restitution request within 30 days. She acknowledged there was a “danger” the Supreme Court could ultimately void the restitution because the prosecution was not prepared at sentencing.

Neagos did not submit his request for nearly $14,000 in restitution until 54 days later, in violation of Carlson’s order. Brassill’s attorney pointed out Neagos, in reality, had the estimate of damages within 19 days of sentencing.

“The district attorney’s office does need to get their act together on this,” Carlson agreed at the restitution hearing. “The prosecution’s on warning that if I give them a deadline like that in the future, that (their restitution request is) going to be denied.”

Because the hearing occurred within the 91-day deadline, however, Carlson granted the restitution request “this one time only,” notwithstanding Neagos disobeying her order.

A duty to pursue restitution information

On appeal, Brassill argued the prosecution made “no effort” to determine a restitution amount by the time of sentencing, which Colorado law required Neagos to do regardless of the 91-day deadline.

“The way the state gets 91 days … is if that information is unavailable,” defense attorney Cassandra Zobel told the Court of Appeals panel during oral arguments. “What we’re asking the (panel) to do is find that the state has to take steps to bring that information to the court before asserting that it was unavailable.”

The government insisted there was “simply no obligation” in the law for prosecutors to prepare their restitution requests prior to sentencing. Moreover, Carlson was not permitted to set her own, shorter deadline for receiving the restitution details.

“That’s just not the authority courts have,” said Senior Assistant Attorney General Brock J. Swanson.

Wrong, the appellate panel responded.

“The prosecutor’s failure to comply with that order was in defiance of the district court’s inherent authority and contrary to the directives in Weeks,” Schutz wrote.

He elaborated that prosecutors do, in fact, have an obligation to try to calculate restitution prior to sentencing, with the 91-day deadline kicking in only when such calculations are not feasible. Going further than the Supreme Court’s opinion in Weeks, Schutz emphasized the law’s “primary objective” is to resolve restitution at the time of sentencing.

“By not resolving restitution at sentencing, the victim is deprived of the psychological benefits of finality of the proceedings; the defendant is required to agree to pay an unknown amount of restitution,” he wrote, “and the prosecutor, defense counsel, and the sentencing court are required to expend additional time and public resources resolving financial disputes that could have been completed before sentencing through the exercise of reasonable diligence.”

Under the circumstances, the panel concluded Neagos failed to diligently pursue restitution details in Brassill’s case. However, because Carlson ultimately ordered restitution within the 91-day deadline, Brassill’s obligation to pay was valid.

The case is People v. Brassill.