Adams County waited too long to challenge DIA’s noise modeling system, Colorado justices rule

Adams County and its municipalities waited two decades too long to sue Denver over its failure to use a noise monitoring system at Denver International Airport, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Monday, permitting the continued use of an outdated and inaccurate method for modeling noise instead.

The ruling comes at a time of significant expansion in the airport’s operations, with DIA adding more airlines and flights amid major infrastructure upgrades to process more passengers at security checkpoints.

Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. wrote that the court’s straightforward job was to assess when Adams County discovered Denver had breached its contract, even if Adams County did not realize for years how the failure to use a noise monitoring system was creating a problem. It did not matter, he explained, that Adams County believed Denver’s noise modeling system was producing roughly the same results as the noise monitor, even as the model began to understate violations as time passed.

“We acknowledge that, as Adams notes, Denver did withhold data,” Samour wrote in the Jan. 29 opinion. “We do not condone Denver’s conduct.”

However, it was also true Adams County knew around 1995 that Denver was not relying on a noise modeling system as required, and instead chose to let the status quo continue.

“(F)ar from being a case in which the defendant hid the ball from the plaintiff, this is a case in which the defendant handed the ball to the plaintiff and the plaintiff examined it and returned it,” Samour noted.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs and for Denver did not immediately provide comment on the decision.

Since opening in 1995, DIA has become one of the busiest airports in the world, with 69.3 million passengers traveling through DIA in 2022. The airport anticipates handling 100 million passengers by 2032, and welcomed its 25th airline this month.

Two methodologies diverge

The controversy with Adams County stemmed from the intergovernmental agreement requiring Denver to report airport noise levels annually, with financial penalties for decibel levels exceeding the maximum.

From the beginning, the airport has used a system that models noise levels, called ARTSMAP. In 1992, Adams County sued Denver, arguing a noise monitoring system, rather than a modeling system, was required.

At the time, the ability of microphone-based monitoring systems to distinguish airplane noise from other ambient sound was rudimentary. However, a consultant believed technology had improved enough to set up such a noise monitor, called ANOMS. Based on the promise of installation, the lawsuit was dismissed.

After the airport opened, both types of systems were operational. Still, Denver relied on the modeling system for its reports. Adams County sued Denver in 1998 for noise violations, but did not seek to force Denver to use the monitoring system.

More than a decade later, in 2014, Denver provided its annual noise report with data from both ARTSMAP and ANOMS. Adams County processed the noise monitoring data and found that instead of the minor variation in decibel levels between the two systems that existed in the late 1990s, ARTSMAP was modeling vastly fewer noise violations than the monitoring system was catching.

Once again, Adams County sued, along with three municipalities, this time seeking a declaration that Denver had breached its contract by continuing to use the outdated and inaccurate noise modeling system to report violations. Denver responded the three-year statute of limitations began — at the latest — in the mid-’90s, when the airport opened and Adams County knew Denver was using noise modeling instead of noise monitoring.

Then-Jefferson County District Court Judge Christie A. Bachmeyer disagreed, noting Denver’s annual obligation to report noise levels meant Adams County had a new claim every year that Denver did not use ANOMS. She awarded $33.5 million for dozens of noise violations.

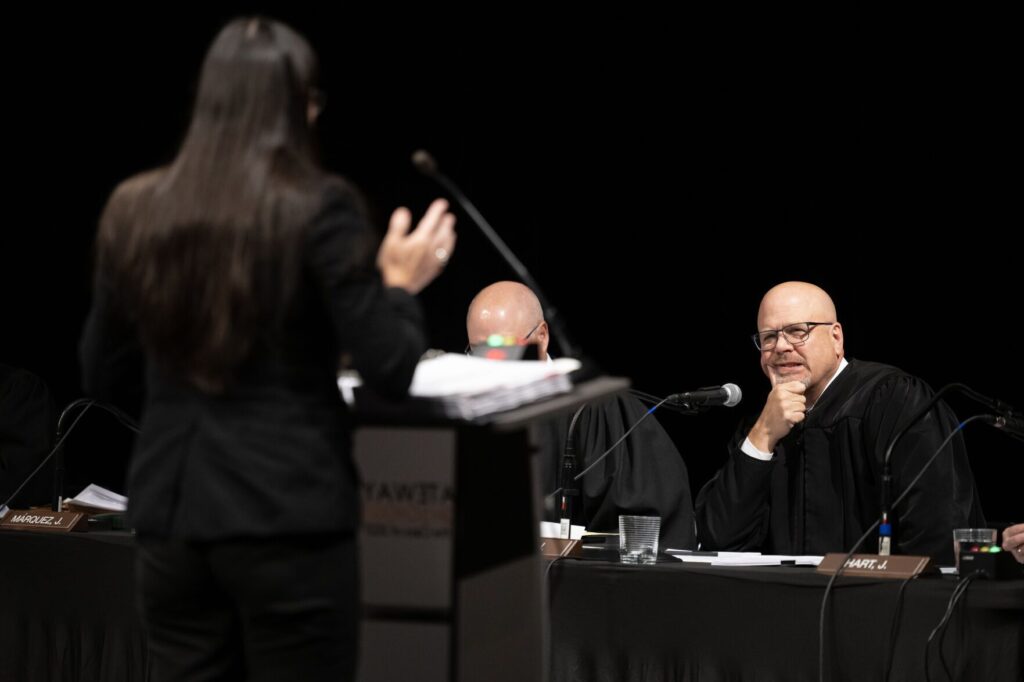

A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals declined to endorse Bachmeyer’s conclusion about the annual opportunity Adams County had to sue, but agreed Adams County could not have taken action until after it realized the drastic underreporting of noise violations from the modeling system.

“Not only was Adams unable to prove that any damages flowed from Denver’s use of ARTSMAP rather than ANOMS” before 2014, wrote Judge Rebecca R. Freyre, “but it also had no incentive to sue.”

‘Gamble didn’t pay off’

The Supreme Court, however, slammed the Court of Appeals for concluding the timeliness of a lawsuit depends upon an “incentive to sue” and a plaintiff’s awareness it is being harmed. Instead, the question was when the plaintiff discovered the breach of contract. For Adams County, that discovery occurred 20 years ago, and the county chose to let it be.

“Under a damages-based approach, plaintiffs might choose to delay the filing of their suit to allow damages to increase or until litigation is more advantageous. This case is a prime example,” Samour wrote. “But by acquiescing to Denver’s use of the ARTSMAP system for nearly two decades, Adams played the percentages, and in the end, its gamble didn’t pay off.”

Samour clarified the decision does not affect Adams County’s ability to continue to hold Denver financially liable for ongoing noise violations.

Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter did not participate in the appeal.

The case is City and County of Denver v. Board of County Commissioners et al.