Boulder County judge wasn’t obligated to bail out self-represented defendant, appeals court rules

Colorado’s second-highest court concluded last month that a criminal defendant in Boulder County was not unfairly forced to choose between his rights to a speedy trial and to an attorney, and, when he elected to go without an attorney, the trial judge was not obligated to save him from his own poor performance.

Jurors convicted Timothy Mark Gemelli in 2019 of multiple counts of sexual assault on a child and he is serving an indefinite prison sentence. After being incarcerated for several months before trial, he indicated he would represent himself and be tried quickly rather than delay the proceedings at his attorney’s request.

On appeal, Gemelli advanced several arguments, including that he had not validly given up his constitutional right to an attorney because at the time, he was “worn down” by the pretrial incarceration. Moreover, Gemelli believed his performance as his own lawyer was so inept that the trial judge was required to take action to protect his right to a fair trial.

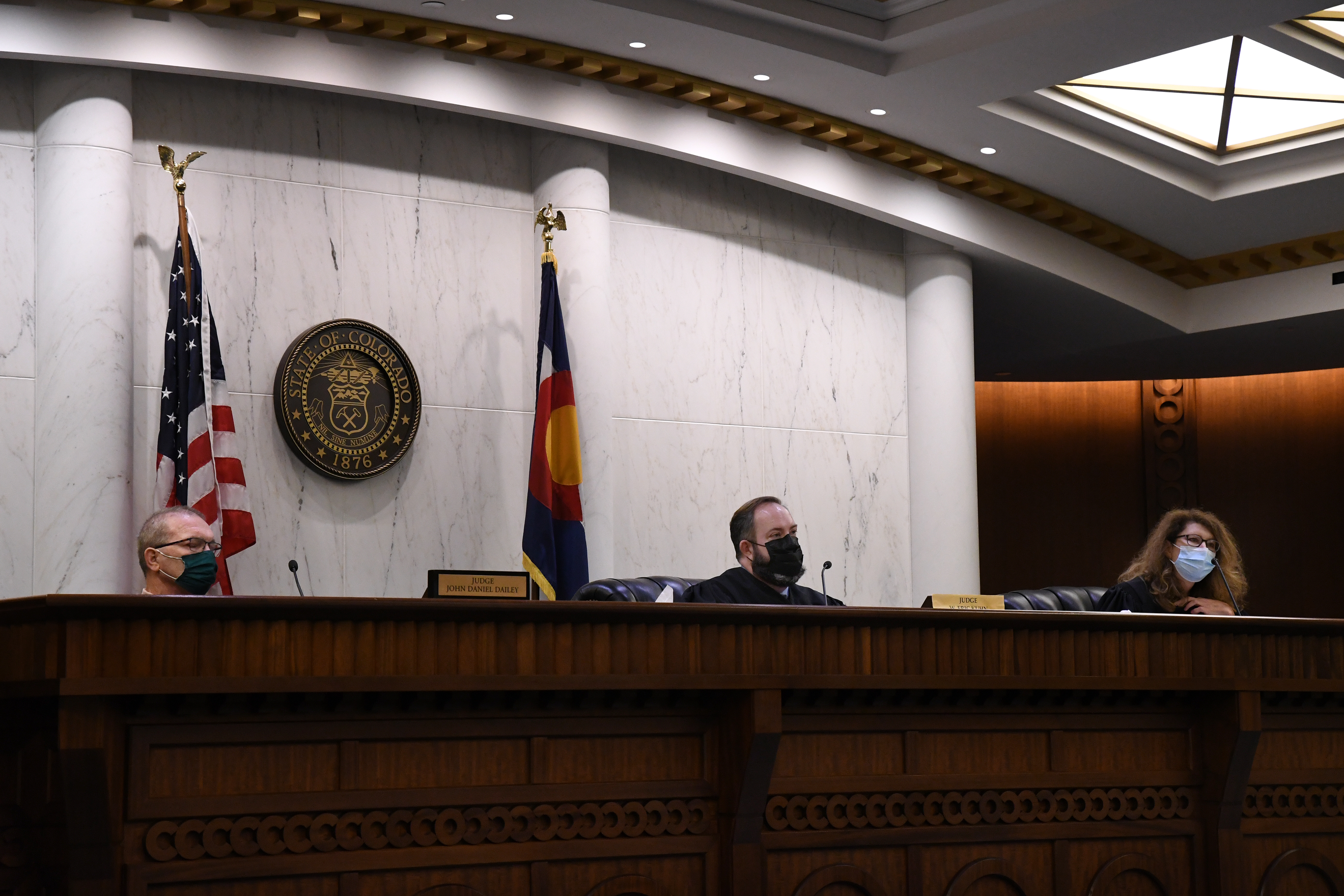

A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals disagreed on both fronts.

“To be sure, Gemelli faced a difficult decision. He could legitimately have perceived both of his options – continue with counsel but agree to a continuance or proceed pro se (without a lawyer) and maintain the trial date – as less than ideal,” wrote Judge Elizabeth L. Harris in the Dec. 14 opinion. That choice, she added, was not “constitutionally offensive.”

Moreover, the panel found no support for the idea that a defendant in Gemelli’s situation could perform so badly that a trial judge must appoint an attorney to take over for him.

“The court was neither obligated nor authorized to relieve him of the consequences of his decision,” Harris wrote.

Case: People v. Gemelli

Decided: December 14, 2023

Jurisdiction: Boulder County

Ruling: 3-0

Judges: Elizabeth L. Harris (author)

John Daniel Dailey

Stephanie Dunn

Background: Accused of molesting several girls in Louisiana, Slidell man convicted in Colorado, sentenced to 60 years

Gemelli stood trial after a jury acquitted him in Louisiana for similar allegations that occurred prior to his child abuse in Colorado. He pleaded not guilty in July 2019 and a trial was scheduled for early December.

In the fall, Gemelli’s attorney disclosed he needed more time to prepare, but his client was frustrated with being held in custody in Louisiana and Colorado for so long. If Gemelli’s bond were reduced, there would be no issue, the lawyer continued. But if Gemelli remained incarcerated, he would likely choose to represent himself on the scheduled trial date.

District Court Judge Bruce Langer denied the bond reduction and Gemelli quickly indicated he would act as his own lawyer.

“I’m just not prepared to sit here for another nine months. I’ve been in jail going on three years for false allegations, and I don’t have much choice,” Gemelli said.

Langer appointed an advisory counsel to assist Gemelli, and, if requested, step in to represent him. Gemelli proceeded through a six-day trial and did not ask for his advisory counsel to take over. Jurors found him guilty.

On appeal, Gemelli claimed his choice of a speedy trial over an attorney was a “product of being worn down from three years of pre-trial incarceration.” During oral arguments, however, the panel wondered why Gemelli was not entitled to make that choice.

“Isn’t that one of the reasons why a defendant might reassert his right of self-representation? To regain control over, ‘I wanna go to trial within a certain period of time?'” asked then-Judge John Daniel Dailey.

Public defender Jessica A. Pitts argued that when a defense lawyer needs more time but the client threatens to go pro se if a postponement occurs, “the court should say, ‘I’m granting the continuance over defendant’s personal request. I’m denying the defendant’s request to go pro se.'”

“Wow,” responded Harris. “Why can’t he decide which is more important to him? That’s his choice.”

Pitts also argued the voluminous number of objections the trial judge sustained against Gemelli – 374 – indicated Gemelli’s defense of himself was going “so off the rails” that an intervention should have happened to potentially reappoint counsel.

“Can you point us to any case where a court has imposed a lawyer on someone who is exercising their right to self-represent?” asked Judge Stephanie Dunn.

In the panel’s opinion, Harris cited a 1985 decision of the Colorado Supreme Court that acknowledged a pro se defendant may demonstrate “such a level of ineptitude” that the trial becomes constitutionally unfair. However, the Supreme Court did not impose an obligation for trial judges to force a lawyer upon a defendant who already rejected one.

Moreover, the panel was unsure how badly a pro se defendant’s performance needed to be to trigger an override of the right to represent oneself.

“(A)ny rule recognizing that distinction would be at odds with all of the principles underlying the right of self-representation,” Harris added.

The case is People v. Gemelli.

michael.karlik@coloradopolitics.com