Colorado Supreme Court weighs immunity for speeding officer who killed 2

In July 2018, Officer Justin Hice of Olathe was in pursuit of a speeding car, accelerating to more than 100 mph before he accidentally struck a different vehicle and killed its two occupants.

Last year, the state’s Court of Appeals concluded Hice was not shielded from liability under the broad immunity Colorado law provides to public entities and employees. The court laid down a straightforward rule: If an officer in pursuit exceeds the speed limit and fails to use his lights or siren at any point, he is not immune for any injuries he causes.

During oral arguments before the Colorado Supreme Court on Tuesday, however, the justices suggested the Court of Appeals may have gone too far.

“I just struggle to find anything that explicitly tells us when the lights or sirens are supposed to come on,” said Justice William W. Hood III.

The Supreme Court acknowledged there are multiple dimensions to the lawsuit against Hice and the town of Olathe. On the one hand, the Colorado Governmental Immunity Act is meant to protect emergency responders who act quickly without fear of liability. On the other hand, the legislature added a condition to that immunity – the use of lights or sirens when exceeding the speed limit.

Although it was undisputed Hice activated his lights by the time he crashed into the van carrying Walter and Samuel Giron, the legal question is whether Hice forfeited his immunity by spending the bulk of his pursuit going well above the speed limit without any warning to motorists.

The attorney for Hice argued in favor of largely allowing officers to decide for themselves that activating their warning signals is not always prudent, even in a high-speed chase.

“Whether that might seem unusual to us as we sit in a courtroom and debate this academically, out in the real world this is something that they occasionally do,” said Winslow R. Taylor III.

“One of the objectives is to protect public safety broadly, right?” countered Hood. “So a requirement that errs in favor of having police officers activate lights and sirens seems to better accomplish that, wouldn’t you agree?”

Hice was monitoring traffic along U.S. Highway 50 when he saw a white Toyota exceeding the speed limit. Hice gave chase, which lasted for 36 seconds. He never activated his siren, but turned on his lights for the last five to 10 seconds. At an intersection, the Girons’ van turned in front of Hice. He hit the van going at least 75 mph.

The Girons’ surviving relatives sued Hice and the town of Olathe. In response, the defendants invoked the Colorado Governmental Immunity Act. Under the law, immunity only applies to emergency vehicles exceeding the speed limit during a pursuit if they are “making use of audible or visual signals.”

Montrose County District Court Judge D. Cory Jackson initially dismissed the lawsuit after finding Hice used his emergency lights and did not create an unreasonable risk of injury in his pursuit. Jackson credited the testimony of current and former police officers over the motorists who Hice passed at high speed and who came close to crashing into Hice themselves.

Last July, a three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals reinstated the lawsuit, finding it did not matter that Hice turned on his lights in the final seconds before impact.

“For Officer Hice and Olathe to be entitled to immunity, Officer Hice would need to have activated his emergency lights or sirens the moment he exceeded the speed limit during his pursuit,” wrote Judge Sueanna P. Johnson.

On appeal to the Supreme Court, multiple outside groups weighed in. The Colorado State Patrol alleged that courts should not second-guess the “split second decisions” of first responders. The Colorado Trial Lawyers Association argued the Court of Appeals’ rule would only be a problem for emergency personnel who break the law.

The defendants, meanwhile, warned the Court of Appeals’ rule could apply in absurd situations: eliminating immunity if an officer fails to activate his lights for one second at the beginning of a pursuit when he is traveling 1 mph above the speed limit, even if his lights are on the entire time afterward.

“Each side has done a pretty good job of conjuring hypotheticals that make the other side’s position look a little silly and extreme,” Hood observed. “It doesn’t seem so unreasonable to me to ask police officers, particularly when they are doing this kind of patrol duty, to at least activate their lights as soon as they’re going to engage someone who’s speeding. They know that they’re gonna have to speed in order to catch up.”

“I don’t think you would say we could have a rule where each individual officer gets to decide in each individual case when I should turn my lights on,” added Justice Richard L. Gabriel.

Taylor acknowledged that if Hice had collided with any other vehicle before he turned his lights on, there was no question he would face liability. In the Girons’ case, he continued, it was not clear the failure to turn on the lights initially could have affected the ultimate impact.

Damon J. Davis, representing the Girons’ family, responded that even in a situation where an officer briefly exceeds the speed limit without lights or sirens – and the crash happens miles down the road – the officer may not have liability. But they will lose immunity.

“The rule is you have to turn the lights and sirens on,” Davis said. “It makes it safer. That’s what the legislature has decided.”

“Why wouldn’t having a rule that says you lose immunity if you didn’t turn the lights on at a time when it would affect the accident … why wouldn’t that have the same deterrent effect?” wondered Gabriel.

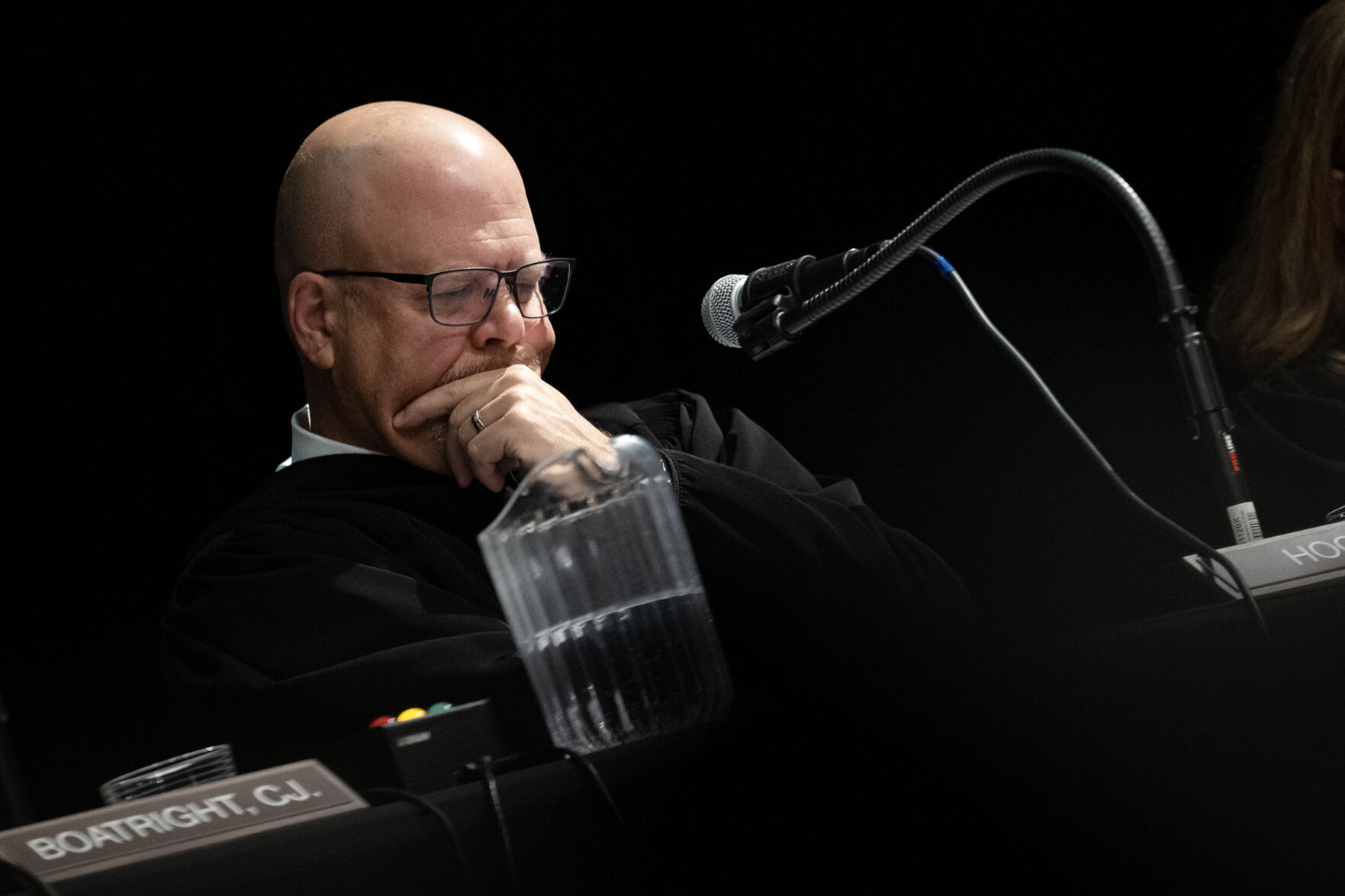

Chief Justice Brian D. Boatright and Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. were not present for the arguments. They represented the Supreme Court at the funeral of former Chief Judge Gilbert Martinez of El Paso County. Justice Monica M. Márquez, who presided in Boatright’s absence, said the two will still participate in the case.

The case is Hice et al. v. Giron et al.