Colorado Supreme Court rejects expanded role for juries in analyzing prior convictions

The Colorado Supreme Court on Tuesday rejected the argument that juries should be the ones who increase the severity of a defendant’s convictions by evaluating prior convictions – meaning judges alone retain the authority to transform a misdemeanor into a felony in some instances.

The question of whether juries should decide beyond a reasonable doubt whether a defendant has prior convictions could either help, or hurt, the criminally accused. On the one hand, jurors might hear damaging information about a defendant’s past conduct and be more likely to convict. On the other hand, they could conclude the prosecution failed to show the defendant on trial was the same person who allegedly committed previous offenses.

In a pair of rulings, the justices cautioned that their interpretation about the role of juries tracked the U.S. Supreme Court’s own directive about prior convictions. Moreover, the specific offenses before them did not envision juries would be the ones elevating a felony conviction to a more serious felony, or a misdemeanor to a felony.

In the majority opinion, Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. acknowledged that a jury convicting someone of a misdemeanor, only for a judge to transform it to a felony, carried more significant consequences for a defendant’s liberty than simply increasing an existing felony to a more serious felony.

“They include: the loss of the right to vote while incarcerated, the loss of the right to own firearms, the possibility of habitual criminal charges upon the subsequent commission of a felony,” he wrote, “and the inability to obtain certain employment.”

Nevertheless, Samour noted the nation’s highest court has explicitly carved out an exception for the Sixth Amendment’s right to a jury trial that permits judges to use prior convictions to increase a defendant’s sentence.

Justice Richard L. Gabriel, writing in dissent, pointed out the U.S. Supreme Court has never endorsed letting judges alone transform a misdemeanor conviction to a felony. In an unusual move, he suggested the U.S. Supreme Court use the case of Constance Eileen Caswell as an opportunity to address whether judges act constitutionally by doing so.

“I would urge the Supreme Court – whether in this or another case – to clarify whether the prior conviction exception remains viable and, if so, whether it applies in cases like this one,” he wrote.

The public defender’s office, which represented Caswell, did not immediately say whether it planned to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court in response to Gabriel’s suggestion.

A Lincoln County jury convicted Caswell of 43 counts of animal abuse, which is ordinarily a misdemeanor. Caswell admitted she had a prior animal abuse conviction on her record, prompting the trial judge to sentence her for a felony – as Colorado law requires for repeat offenses.

In the second, related case the state’s justices heard, a Denver jury convicted Charles K. Dorsey for failing to register as a sex offender. Twice in 20 years, he did not register by the annual deadline, which is a class 6 felony. After a jury convicted Dorsey the second time, prosecutors showed the trial judge paperwork documenting his prior conviction and the judge sentenced Dorsey on a more serious, class 5 felony.

Both appeals questioned whether the trial judges could use the defendants’ criminal histories to increase the severity of the convictions, or whether that was a task constitutionally left to their juries.

In Dorsey’s case, the justices easily decided a prior conviction for failing to register was meant to enhance his sentence after a jury verdict. The state Supreme Court agreed Dorsey’s circumstances fit squarely within the U.S. Supreme Court’s precedent, permitting a judge to increase a low-level felony conviction to a slightly more serious felony.

Caswell’s case was different. Three years ago, the state Supreme Court concluded Colorado’s felony drunk driving law required juries to decide beyond a reasonable doubt whether a defendant had prior DUI convictions – the key factor that turns an otherwise-misdemeanor offense into a felony. At the time, the justices warned it may be unconstitutional for a jury to convict someone of a misdemeanor, only to have a judge decide unilaterally whether to increase it to a felony.

But the state Supreme Court clarified its thinking in Caswell’s appeal. Her case was treated as a felony in the trial court, Samour observed, which lowered the potential for unfairness. Further, the U.S. Supreme Court’s directive still applied: prior convictions are not automatically a jury question.

“A prior conviction is a prior conviction, regardless of whether it transforms a misdemeanor into a felony or not,” Samour wrote.

In his dissent, Gabriel argued that increasing a misdemeanor to a felony “changes the very nature of the offense.” He believed the Colorado Supreme Court was not simply following what its federal counterpart has said about prior convictions, but was stepping outside of the constitutional boundary.

“A critical question in cases regarding prior convictions is one of identity, that is, whether the defendant presently before the court committed the prior offense,” he wrote. “I believe that the critical issue of identity must be presented to a jury, which can convict the defendant of a felony only if it finds the fact of identity – and all other facts necessary to establish the prior conviction – beyond a reasonable doubt.”

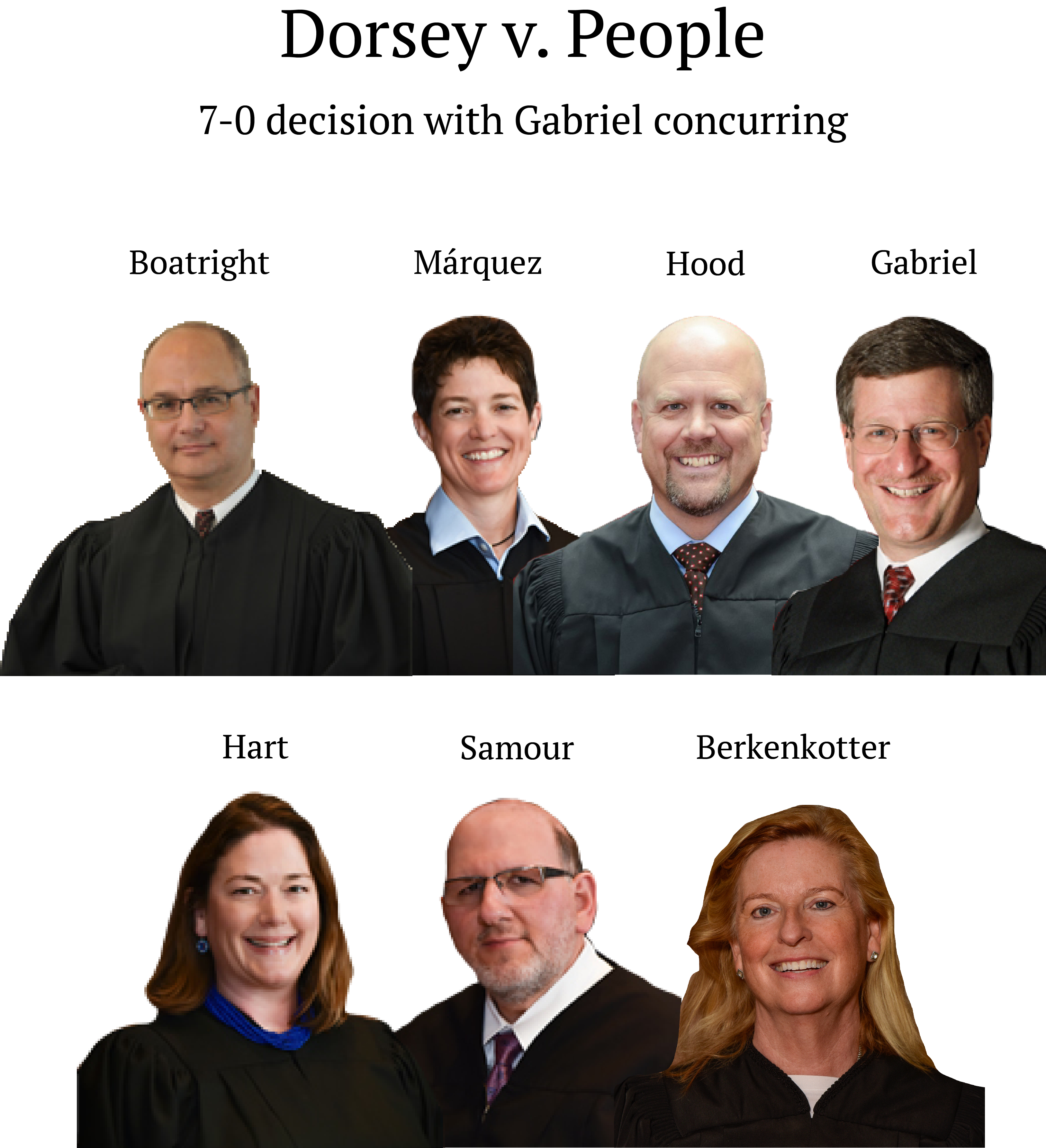

The cases are Caswell v. People and Dorsey v. People.