Colorado Supreme Court says no tribal contact required for potential ‘Indian child’ cases

While recognizing that tribal nations alone are responsible for deciding who qualifies as a member, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Monday that counties are not required to contact tribes to verify whether certain children in custody proceedings are actually American Indian.

Under the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978, child welfare cases trigger protections of tribal interests when they involve an “Indian child,” meaning one who is a citizen of a tribal nation or who is eligible for membership through their parent. If state judges know or have “reason to know” a child is American Indian, the law’s provisions apply – including the obligation to notify the child’s tribe.

The state Supreme Court, however, examined what Colorado’s own version of ICWA requires when judges have some information suggesting a child is American Indian, but not enough to give them reason to know. In those situations, must the government contact any relevant tribes to ask about a child’s possible membership?

No, the court concluded.

When a county’s human services department hears about a child’s potential tribal lineage, “the department must earnestly endeavor to gather additional information that would assist the court in determining whether there is reason to know that the child is an Indian child,” wrote Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter in the court’s Sept. 11 opinion.

But that investigation should not amount to a “predetermined checklist of steps that a department must take in every case,” she added.

Kristofr P. Morgan, an attorney who argued in favor of involving tribes in counties’ investigations, said that despite the court’s decision, Colorado should still use “best practices” in order to comply with the original spirit of ICWA.

“It is disappointing that Colorado’s ICWA statute is being implemented in a way that excludes Indian tribes from the process of determining whether an Indian child is involved in a child welfare proceeding,” he said. “ICWA was enacted to give Indian tribes a voice in the process, and that cannot occur when they do not receive notice of a proceeding.”

Congress originally enacted ICWA after learning of the large number of American Indian children being removed from their households into non-tribal families and institutions – accounting for up to 35% of tribal children. With a history of forcing children into schools that eradicated tribal culture and enabling unjustified adoptions of children into non-tribal households, the government now attempted to prevent the breakup of American Indian families through ICWA.

One year ago, when interpreting the requirements of ICWA, the state Supreme Court determined family members’ claims of tribal lineage in a child welfare case were not enough to give judges reason to know that they were dealing with an American Indian child. Instead, under Colorado’s own ICWA laws, the judge must direct the county to perform “due diligence.”

However, lawmakers never specified what “due diligence” looks like, and the justices at the time refrained from issuing their own expectations about counties’ investigations.

In the current case before the Supreme Court, Adams County initiated a child neglect case and took custody of a newborn child based on the mother’s alleged drug use. A judge ultimately terminated the mother’s legal rights over the child.

During the proceedings, the mother thought she had Cherokee or “Lakota Sioux” heritage, but it was not until the state’s Court of Appeals reviewed the case that Adams County investigated the assertion. The appeals court did not require the county to contact the Cherokee or Sioux nations, and there was no tribal notification. Nonetheless, the court ultimately agreed there was no reason to know the child was American Indian, so ICWA’s protections did not apply.

The mother appealed to the Supreme Court. Because tribes alone decide who is a member of their nations, they will provide the only reliable answer about who is an American Indian child, her attorney argued.

Adams County told the justices that not all tribal nations respond promptly to such inquiries, and government agencies should not be “inundating” tribes without reliable information that a child is American Indian.

“I think the response would be, ‘Well, it’s certainly a good place to start,'” countered Justice William W. Hood III during oral arguments.

The Supreme Court ultimately sided with Adams County. The legislature did not require tribal contact as part of due diligence, Berkenkotter noted. Moreover, involving tribes in child welfare proceedings when there is not yet reason to know a child is American Indian would run contrary to the law.

It would “necessarily require notice in some instances in which we have held that none is required,” she wrote.

The Supreme Court also laid out a definition for due diligence, requiring counties to ask why a parent believes they have tribal lineage and what the source of that information was. Counties must then go to the source and other family members who appear to have more information.

However, Berkenkotter clarified, counties do not need to “exhaust every possible option” when investigating a child’s American Indian status.

Zaven “Z” Saroyan, an attorney with the Office of Respondent Parents’ Counsel who also supported a requirement for tribal contact, said the exclusion of tribal nations in counties’ investigations would not be in the best interests of children.

“It is now up to the Colorado legislature to enact comprehensive ICWA legislation to, among other things, require notification to tribes to protect tribal sovereignty,” he said.

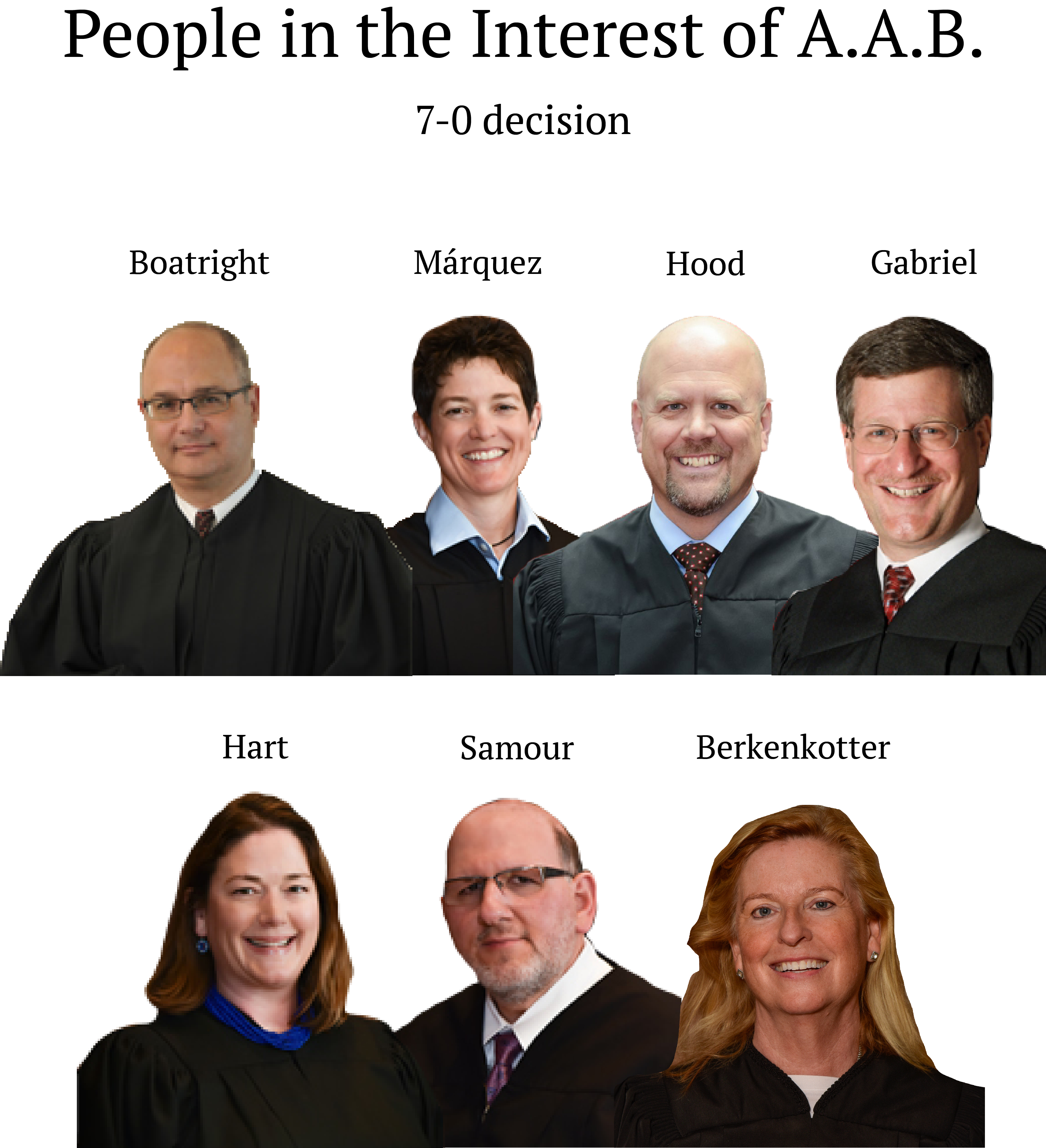

The case is People in the Interest of A.A.B.