More than a half dozen Colorado judges still haven’t filed financial disclosure

More than a half dozen Colorado judges are still delinquent in updating missing personal financial disclosure statements with state officials, despite a Denver Gazette investigation that flagged them about the problem two weeks ago.

There were 15 judges delinquent as of Thursday – one of them on the Appellate Court bench – but the number more than halved after The Denver Gazette sent each of them an email asking for a comment or explanation why.

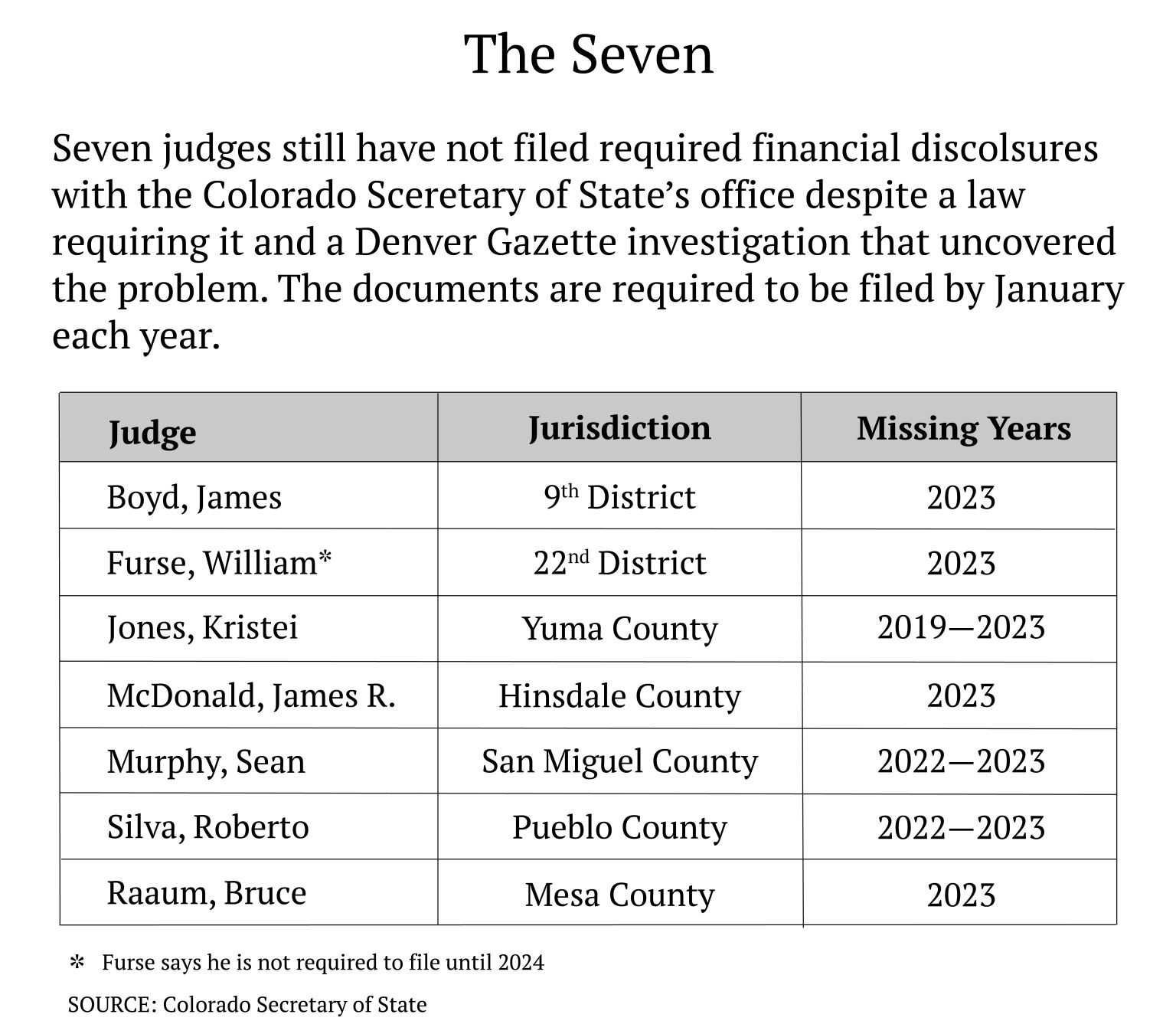

The Secretary of State’s Office said seven judges from a list of nearly 60 did not have financial disclosure forms on file this year – some of them for even longer – following the Denver Gazette’s investigation that ultimately revealed nearly 1 in 6 judges across Colorado had failed to file the document despite a law requiring it.

The disclosures are a financial accounting of a judge’s personal holdings, as well as those of their family. It is a misdemeanor punishable with a fine up to $5,000 to willingly not file. Public officials – from the governor and legislators to county judges and members of certain boards and commissions – are required to file the disclosures with the Secretary of State’s Office each January.

The original list of judges without filings grows even longer when senior judges, those who officially retired but remained on the bench in a limited capacity, are added. Nearly all of the senior judges – there are 50 – hadn’t filed the document with the secretary of state since retiring, some longer than a decade ago, although they do file them with the judicial department as a requirement to be a senior judge. There is no specific exemption that says senior judges are not required to file the document with the secretary of state.

Several judges contacted The Denver Gazette last week to say they had filed the disclosure following the newspaper’s story, some even producing fax logs or copies of the document as proof. A handful pointed to emails sent to The Denver Gazette when the initial story broke in which they said they had taken care of the problem. Many called the missed filings “an oversight.” One said she simply mistyped the email address to make the filing, but did not say whether the email had bounced back undelivered.

A Secretary of State’s Office spokesman said it double-checked its records and could not find disclosures for the seven, but did for the remainder. The office did not immediately say whether senior judges were in compliance. There is no automatic confirmation when a filing is made that shows it’s been accepted.

Yuma County Court Judge Kristei Jones hasn’t filed a disclosure since he was appointed by then-Gov. John Hickenlooper in August 2018, secretary of state records show. The former mayor and city councilman of Wray on Colorado’s Eastern Plains is a rancher with no law degree, other records show. His position is a part-time one and Yuma County is one of the smaller Colorado counties where a county judge need not be a lawyer.

Jones did not respond to emails seeking comment.

When contacted, two judges told The Denver Gazette last week that they were filing the disclosures immediately and offered no explanation why they hadn’t done so until now. A third judge said he ignored the initial story, believing he had properly filed the disclosures previously, only to realize now that he had not.

And Denver District Judge Lisa Arnold emailed The Denver Gazette this week to say her “current disclosure is filed” and that she would “file backdated ones as the info … I need to complete them is sent to me.”

Arnold had not filed any disclosures since she was appointed to the bench in January 2020, The Gazette previously reported.

One of the seven – Mesa County Court Judge Bruce Raaum – insisted he had faxed his disclosures both times The Denver Gazette contacted him, in July and again in August, and provided fax logs to show he had. The Secretary of State’s Office on Friday said it did not have any document from Raaum.

Sedgewick County Court Judge Myka Landry said “although my oversight and the resulting inquiry has caused me much angst,” she was “grateful” to learn that it was an email problem that kept her filing in July from getting to the Secretary of State’s Office. She said the oversight shouldn’t have happened and that she doubted “it will ever happen again.”

As before, several judges again did not respond to Denver Gazette emails seeking comment or explanation, including Appeals Court Judge Elizabeth Harris.

Harris had previously told the newspaper in July that she would check on her two missing disclosures – 2016 and 2020 – but then did not respond to additional emails asking about the outcome of her inquiry. The Secretary of State’s Office said Harris filed the missing disclosures Thursday, a day after The Denver Gazette emailed her again.

One new judge, 22nd Judicial District Judge William Furse in Durango, said he doesn’t think he’s violated any law by not filing. The Denver Gazette had earlier identified him as one of the judges the Secretary of State’s Office said had not filed a disclosure for 2023.

Furse said he believed the statute applies to him only after he was actually sworn in to the job and not before.

Gov. Jared Polis officially appointed Furse on Aug. 31, 2022 to fill a vacancy that was to come with the retirement of District Judge Douglas Walker. But Furse didn’t begin his term until Walker left on Jan. 10, 2023.

The disclosure law only says that judges are required to file by the Jan. 10 “following his or her election, reelection, (or) appointment.”

Furse, who had been the district attorney for the 22nd Judicial District and had previously filed the annual disclosures until he left that office in 2020, told The Denver Gazette he’d file his disclosure as a district court judge next January – a year after he’ll have already been on the bench – and not before.

“I’m of the mind that I’m not required to disclose until later this year or to disclose information that was before the effective date of my appointment,” Furse said in a telephone interview.

Furse added in an email: “Again, it is my intent to fulfill my judicial financial disclosure requirements when this time comes” on Jan. 10, 2024.

The judicial department has said it does not interpret any laws unless it is a matter of litigation, and it does not interpret laws for individual judges. The department sends out a yearly reminder to all judges about their obligation to file the required disclosure forms, even if there are no changes to report.

Rep. Mike Weissman, who chairs the House Judiciary Committee, said the spirit of the law shouldn’t be ambiguous.

“Any judge who is presiding over cases from the bench and deciding Coloradans’ rights under the law should have a financial disclosure on file, regardless of other provisions in the disclosure laws about timing of those filings,” Weissman said. “If there needs to be a legislative change to ensure the law is clear on that point, then we will look at that.”

That some judges still have not filed their disclosures after the newspaper stories troubled Weissman.

“I really hope any judicial officers not yet in compliance with filing requirements will prioritize getting their filings in,” Weissman said.

Following The Denver Gazette story, the Colorado Commission on Judicial Discipline requested extensive information about the entire filing history of more than 100 judges – the 56 identified by the newspaper who are still on the bench and the 50 senior judges – from the Secretary of State’s Office, according to emails obtained through an open records request.

The information provided to the commission showed that some of the judges had a history of missed filings that extended further back than just the years identified by The Denver Gazette, according to the emails.

The commission’s work by law is secret so it’s unclear if it’s launched a full-blown inquiry. Outcomes of official investigations, under the current rules, are public only when a recommendation for discipline is made to the Colorado Supreme Court.

Censures are generally private, which means the public never learns of them except in an annual report that describes them generally without identifying the offending judge.

Voters will be asked in 2024 to change how the state’s judicial discipline system works, including when investigations become public.