Q&A with Thomas Dybdahl | Author and ex-public defender talks about the Brady rule, wrongful convictions

In late March, a 60-year-old decision of the U.S. Supreme Court, Brady v. Maryland, surfaced in the news.

A federal judicial nominee from Colorado, U.S. Magistrate Judge S. Kato Crews, blanked at his confirmation hearing when U.S. Sen. John Kennedy, R-La., quizzed him about the significance of the case.

While those familiar with Crews were sympathetic to the gaffe, it provided an opportunity to remind the public about Brady’s central holding: Prosecutors must turn over favorable evidence to the defense that is material to guilt or punishment.

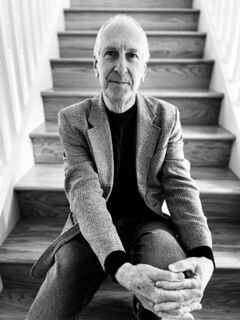

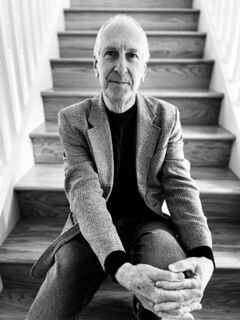

Thomas L. Dybdahl, a former public defender in Washington, D.C. who now lives in Boulder, recently published a book on the subject: When Innocence Is Not Enough: Hidden Evidence and the Failed Promise of the Brady Rule. In it, he noted that, in one study, more than half of all wrongful convictions were the product of government misconduct, and the most common error was withholding “Brady material.”

Dybdahl spoke to Colorado Politics about his book and the ways in which Brady remains more aspirational than real.

FAST FACTS:

- Thomas L. Dybdahl was a staff attorney for 13 years at the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia.

- In that time, he tried 25 murder cases.

- Dybdahl has degrees in law, journalism and theology.

- He now lives in Boulder.

Colorado Politics: Could you explain what the Supreme Court intended with its original Brady decision and how, with the court’s subsequent reinterpretation of Brady, the rule for prosecutors looks a little different today?

Thomas Dybdahl: Very quickly, the facts of that case: John Brady and another man were accused of murder as part of a robbery plan. They were tried separately because each of them said that the other person had done the killing. Brady was tried first but he said the other man, (Charles) Boblit, had actually done the killing.

Brady was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. But after he was sentenced, the lawyer who was working on his appeal learned that the prosecutor had not disclosed a statement in which Mr. Boblit said, actually, he was the killer. So the court said they should have disclosed that because it might have changed the jury’s mind on whether to give John Brady the death penalty because he wasn’t the actual killer.

Out of that came the Brady rule: In a criminal case, the prosecutor is required to disclose favorable evidence to the defense if it’s material to guilt or punishment.

It’s supposed to make trials fair. The concept is the state, the government, is focused on justice. Even as they’re prosecuting someone, if they uncover evidence suggesting that person might not be guilty or that might mitigate the crime or the sentence, they should disclose that in order to reach a fair result. They shouldn’t convict someone while hiding evidence.

The problem is twofold: Prosecutors are not over-fond of the rule because it’s telling them even as you’re prosecuting someone, you have to help the other side. And if you disclose information, it’s gonna hurt your case. It’s not so much that they’re deliberately trying to convict someone that’s innocent. But it’s very difficult, first of all, to know what evidence might be helpful and then to disclose it when it may make you lose your case.

And the way the courts have defined “material” is so vague and malleable that in almost any case, they can rule either way. They ended up saying, “We can’t define it, but we can give you an outcome-based determination.” Which is, evidence is material if there’s a reasonable probability it would have changed the outcome of the case. You don’t have to be a lawyer to know that’s very unclear.

So what happens over and over again is that a court will say, “Yes, the prosecutor had favorable evidence. Yes, the prosecutor withheld it and should have disclosed it. But in the end, we can’t say it would have changed the outcome. So no harm, no foul.” That happens 85% of the time and prosecutors have very little incentive to disclose evidence because even if they don’t, it’s likely they’ll get nothing but a scolding and they will have won a case they might have lost had they disclosed the information.

In my opinion, the Brady rule is weak and ineffectual and needs to be junked.

CP: You make a connection in your book between judges who rule on Brady issues and prosecutors. Specifically, that many judges used to be prosecutors, so they are reluctant to make their former colleagues face consequences or even to name them when writing opinions. Do you think it’s fair for prosecutors to be named and shamed for failing to turn over evidence, when, as you said, there is wiggle room in the Supreme Court’s directive?

TD: I think that the answer is yes, that it’s proper to describe what happened. I want to make a distinction that when a prosecutor fails to disclose Brady evidence, that is misconduct. That is contrary to the rule.

But certainly not every time is it malevolent. I think it’s important to say that many examples of misconduct are not deliberate violations of the rule. They may be inadvertent, but the result is still misconduct.

We want them to change their behavior. If there’s no consequence, if misconduct is never named and is never linked to your behavior, there’s little incentive to be more careful. What we want is not to shame prosecutors, but to make them follow the law.

CP: To what extent do the elected district attorneys and appointed U.S. attorneys take responsibility for individual acts of misconduct? Is it a systems problem that the person at the top should take responsibility for?

TD: I think there is often a culture that helps excuse Brady. If you look at prosecutors, what is the way to advance as a prosecutor? It’s to win cases. It’s to get guilty pleas.

But it really shouldn’t be. The goal is supposed to be justice. But if you’ve ever heard of a district attorney say to his underlings, “Great job in this case. You disclosed some Brady information and you lost the case, but that’s your job and I’m really proud of you. Keep up the good work!” It probably has happened, but I don’t think it’s very common.

CP: You write that prosecutors’ concerns about handing evidence over to defendants – that it could potentially name witnesses or implicate national security concerns – are overblown. You also note some states mandate significant transparency so that defendants will know the case against them when they decide to take a plea deal. But prosecutors do have to look out for victims and witnesses and take people off the street who are threats to public safety. So why shouldn’t they have the discretion to pursue cases as long as they act in good faith?

TD: They should and they do, but I think that they can take it too far. All of the states that have more disclosure requirements that, for example, do require disclosure of witness names, make an exception if a prosecutor can say, “I have legitimate safety concerns.” The judge can shield that name, withhold that name or say you don’t have to disclose that.

One thing I think that’s often overlooked by prosecutors is that if they obtain a conviction by withholding Brady information that suggests or could even prove the person they’ve accused is innocent – if they withhold that and the person is convicted – it’s a double problem. Not only are we sending an innocent person to jail, it means the real perpetrator is still out there.

In the case that I primarily write about in my book, the Catherine Fuller murder, I believe that for the real killer of Catherine Fuller – the police and the prosecutor, if they had not hidden information about the real perpetrator – had he been caught and convicted, it would have saved eight young men from 255 years in person. But it also would have spared the life of a young woman who (the alternate suspect) committed a similar rape and murder against in the same area in a very similar manner.

When Brady evidence is hidden and people are wrongly convicted, not only do they suffer, but we suffer because the real perpetrators may go unpunished and commit more crimes.

CP: In talking about the role of judges in evaluating Brady material and ensuring compliance with the Brady rule, it’s very much after-the-fact. Is there anything trial judges can do while the case is unfolding to ensure compliance with Brady?

TD: There’s certainly more that judges could do. In a typical case, assuming a competent defense lawyer and a good prosecutor, you make Brady demands or requests in a letter prior to trial. Sometimes we would list a whole range of material that we believed would be Brady, and we asked that it be disclosed in a timely way.

Certainly judges can get very involved in that, or at least by saying to the prosecutor, “All right, this looks appropriate to me, this request. Have you provided all this information? Have you asked your police officers, your detectives that are working with you, to disclose any of this kind of information?”

Because certainly one of the issues is police do not always give all their information to the prosecutor – and it’s not a defense to a Brady violation to say, “I didn’t know.”

Judges could absolutely take a much stronger role in saying, “I want you to certify to me in open court on the record that you have sought out, asked for, all of this kind of Brady information and disclosed it.” And if they do that, certainly a prosecutor is on notice that he or she better do that or down the road there might be more trouble if something else comes out.

But judges generally take a much more passive role, saying, “You lawyers work it out.” I think that softens then the sense of urgency that a prosecutor might feel.

CP: If the Supreme Court were to erase its line of Brady cases and write a new rule about the obligation of prosecutors to turn over evidence suggesting the defendant did not commit the charged offense, what would you like the rule to say?

TD: Favorable evidence needs to be disclosed, but it is a constitutional violation to withhold evidence that is relevant. The materiality standard is such a high bar.

To make a determination 10, 20, 30 years later that this information wouldn’t have made a difference is often impossible. I think we need a much more transparent system with all of the relevant evidence available to the defense in order to ensure a fair trial.

Brady violations are the single largest cause of wrongful convictions in this country and that’s a disgrace. There are thousands of people who were wrongly convicted and spent decades and decades in jail because prosecutors have wrongly hidden evidence. It’s not just a legal discussion. It’s a very human problem.