Colorado Supreme Court says crime victims can’t be forced to testify simply by being in hearing room

The Colorado Supreme Court clarified the rights of crime victims and the criminally accused on Monday, finding a judge in Boulder County incorrectly ruled a defendant could force his alleged victim to testify because she happened to be in the courtroom during a hearing.

The Supreme Court maintained victims do not have “immunity” from testifying at a preliminary hearing – a type of proceeding for certain crimes in which the prosecution must show probable cause the defendant committed the charged offense. However, if a victim exercises their right to be present for such a hearing, their testimony must come voluntarily or through a subpoena, and not simply at the defense’s request.

“If what the county court did here were acceptable, then victims would have to think twice before attending certain proceedings like preliminary hearings – they would avail themselves of their right to be present at their own peril of being compelled to testify,” wrote Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. in the April 24 opinion.

Chief Deputy Trial Attorney Adam Kendall of Boulder County applauded the justices’ interpretation of the protections granted to crime victims under the state’s Victim Rights Act.

“The testimony of a victim is very rarely necessary at a preliminary hearing in a criminal case,” Kendall said. “This opinion ensures that victims who exercise their right to appear at a preliminary hearing will no longer face the risk of being ambushed.”

In 1992, Colorado voters overwhelmingly approved the Victim Rights Act. Among other things, the law ensures victims have the right to be present at “all critical stages” of the criminal justice process. A preliminary hearing qualifies as a critical stage.

On Sept. 15, 2022, Evan Michael Platteel received a preliminary hearing on charges that he sexually assaulted a woman with force. The victim, identified in court documents as E.G., was present.

Prosecutors called one witness, Det. Scott Byars, who discussed his investigation. He relayed what Platteel told him – that the sexual encounter was consensual – as well as the victim’s statements. However, Byars’ testimony reportedly exposed inconsistencies in E.G.’s allegations that Platteel used force against her.

Platteel’s attorney then moved to call E.G. to testify, arguing there were “two different versions” of E.G.’s force-related claims that she could clear up on the witness stand.

While the parties considered the issue, E.G. attempted to leave. At the defense’s request, retired Judge Frederic Rodgers, who was presiding over the hearing, told the prosecution to retrieve her. The prosecutor informed Rodgers that E.G. was “very emotional,” and the judge allowed her to stay in the hallway until he reached a decision.

The defense pointed out it had a Colorado Supreme Court case in its corner: McDonald v. District Court, a decision from 1978. In that probable cause hearing, the prosecution only called two police officers whose testimony was “almost completely” hearsay – meaning out-of-court statements from the victim. The Supreme Court ruled that because the victim was in the room and could testify “directly from her perception,” the judge should have allowed the defense to put her on the stand.

Rodgers believed Platteel’s situation closely tracked McDonald. He allowed the defense to call E.G., but paused the proceedings so the prosecution could appeal directly to the Supreme Court. Rodgers added the issue “could have been avoided if she were not here.”

The Boulder County District Attorney’s Office warned the Supreme Court that adhering to McDonald in light of the Victim Rights Act’s protections would have a “chilling effect” on victims and test their “resolve” to even participate in the justice system.

Platteel countered the government can avoid any problems by either presenting enough evidence of probable cause or telling victims that if they exercise their right to be present, there is a chance they may be called to testify.

The Supreme Court reached two conclusions. First, the detective’s testimony at Platteel’s hearing demonstrated probable cause, and nothing E.G. said “could have undone or changed” that. While E.G.’s version of events had shifted, preliminary hearings are not trials.

Thus, it “would have been improper for the county court to make credibility determinations, including by attempting to ascertain which of E.G.’s versions of events was most believable,” Samour wrote.

Second, the Supreme Court overruled its McDonald decision to the extent it forces victims to choose between participating in criminal prosecutions and staying home to avoid testifying.

“Such an unenviable choice would chill a victim’s right to attend the critical stages of proceedings, would be inconsistent with the constitutional and statutory goal of honoring and protecting victims, and would contravene the objective of treating victims with fairness, respect, and dignity,” explained Samour.

Justice William W. Hood III wrote separately for himself and Justice Richard L. Gabriel. While they agreed there was probable cause of a crime in Platteel’s case, they did not believe it necessary to overrule McDonald. The Victim Rights Act, explained Hood, does not say judges abuse their authority by requiring victims who are in the room to testify upon request.

“Putting accusers on the stand isn’t inherently abusive. It’s simply an inevitable byproduct of the rule of law,” Hood argued. “It strikes me as overbroad to assume that in every instance calling a victim to the stand at a preliminary hearing would invariably rob the alleged victim of dignity and respect, and subject them to harassment and abuse.”

Scott Jurdem, an attorney for Platteel, told Colorado Politics in a phone message that he had concerns about the majority opinion and called attention to the points made in Hood’s concurrence.

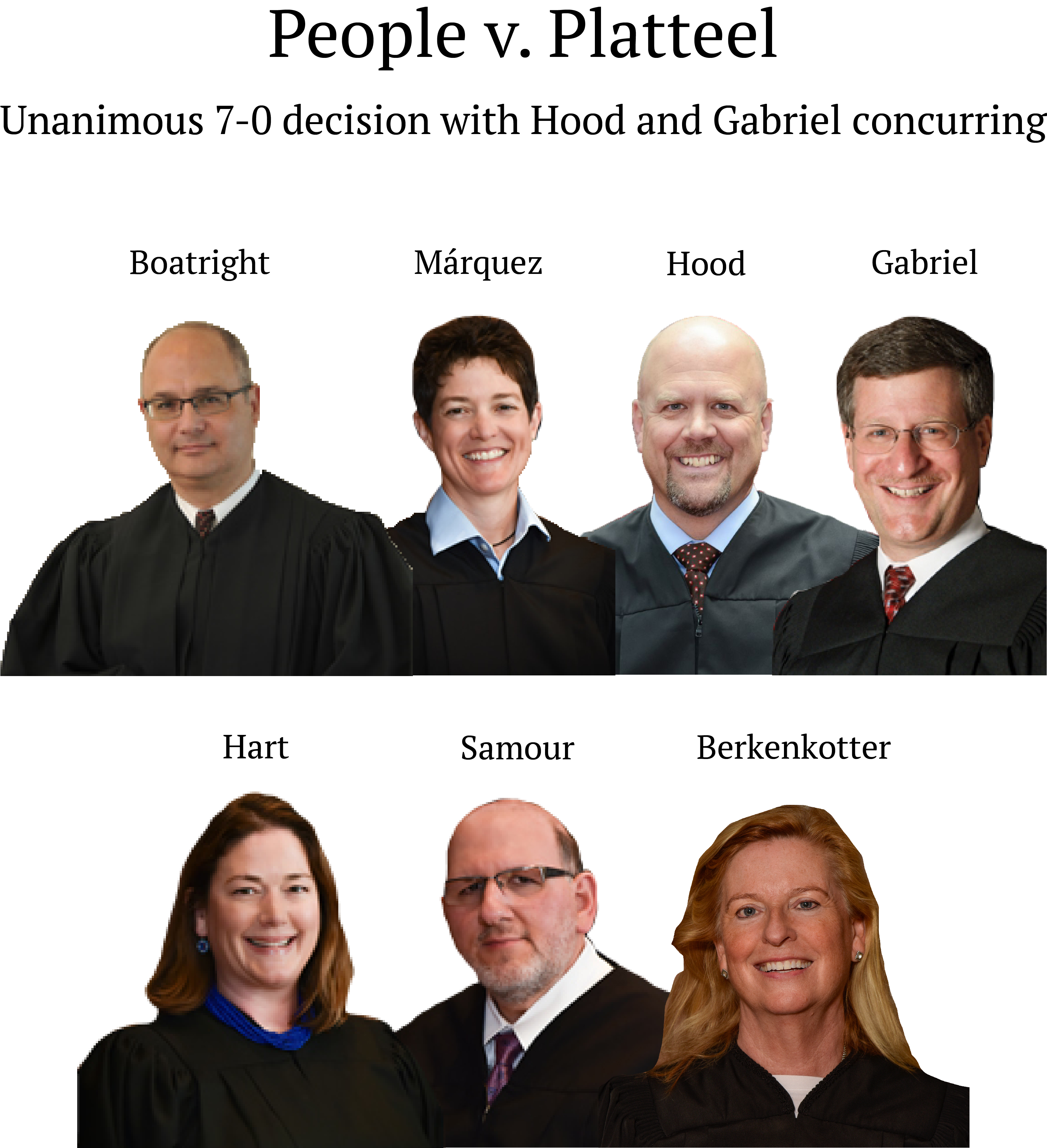

The case is People v. Platteel.