10th Circuit rules Denver police had no justification to search suspect’s backpack

Denver police were unjustified in searching a suspect’s backpack, the federal appeals court based in Colorado ruled on Tuesday, meaning the loaded firearm found inside cannot be used as evidence of a crime.

The Fourth Amendment guards against unreasonable searches and seizures, and there are circumstances under which a warrantless search may be constitutional. But a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit decided officers’ confiscation of Tyrell Braxton’s bag was neither part of his drug-related arrest nor was it a product of law enforcement’s duty to protect Braxton’s property.

The panel relied upon a key fact in Braxton’s arrest: His girlfriend, Tanyrah Gay, was present and asked to take the backpack, but officers repeatedly refused to hand it over.

“(O)ur precedent establishes that officers generally act unreasonably when they ignore or shut down obvious alternatives to impoundment,” wrote Judge Nancy L. Moritz in the March 7 opinion. “And the officer here did just that, failing to offer any reasonable rationale for not at least inquiring further about whether Gay could take the backpack.”

Braxton’s appeal implicated the “community caretaking” function of law enforcement, meaning the non-investigative work aimed at protecting the public. An exception to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement, the community caretaking function is typically associated with searches of abandoned or damaged vehicles that are destined for impoundment. The U.S. Supreme Court has recognized police will “often” remove vehicles to ensure traffic flow and safety, making impoundment-related searches reasonable.

A less common scenario for the courts is the constitutionality of officers searching and impounding a personal storage item, as in Braxton’s case.

In early 2020, a Denver sergeant monitoring cameras along East Colfax Ave. saw Braxton sell drugs to another man outside a convenience store. Two officers arrived, removed Braxton’s backpack and put him in handcuffs. They found cash and a plastic bag on Braxton, which appeared to contain narcotics.

“Hey, get my girl,” Braxton yelled across the street. “Tan! Tanyrah, come here.”

Gay approached the scene and Braxton asked her to “get the money. Bond me out.” In response, Gay asked if she could “get his bag,” and an officer said she could not.

As officers took Braxton to the police vehicle, Gay again said, “I can’t take my backpack?”

“Nope,” an officer replied. Braxton tried to convince police that Gay needed the money in the bag to get him released from jail, and Gay attempted to give Braxton her phone number so he could call her.

Officer Andrew Carman then placed the backpack on the car and removed the items. He found a loaded gun. A federal grand jury subsequently indicted Braxton for firearms-related offenses.

Braxton argued the search of his backpack violated the Fourth Amendment and he moved to have the gun excluded as evidence. At the time, the 10th Circuit had recently decided a case out of Wyoming, United States v. Knapp, which held that an officer’s search of a suspect’s purse was not related to safety or preserving evidence, as the suspect could not even access it.

The prosecution conceded in Braxton’s case that under Knapp, Carman’s search was unconstitutional because the backpack was not related to the drug crime and police had already separated him from the bag. But the government argued another exception to the Fourth Amendment applied: the community caretaking function.

Testifying about Braxton’s backpack search, Carman admitted that he “was searching it for other evidence of the crime we were arresting him for,” but also asserted he had “a duty to protect (Braxton’s) property.”

Even if he had released the backpack to Gay, “we still have to inventory those items in that bag,” Carman testified.

U.S. District Court Judge Raymond P. Moore declined to find police acted unreasonably, saying they were entitled to protect Braxton’s property under their community caretaking function. Moreover, Braxton had not explicitly asked for police to hand over the bag to Gay.

“What I have is a stranger, essentially, saying, ‘Can I take his bag?’ And I do not think that it is inappropriate for the police department to say no in response to that request,” Moore said.

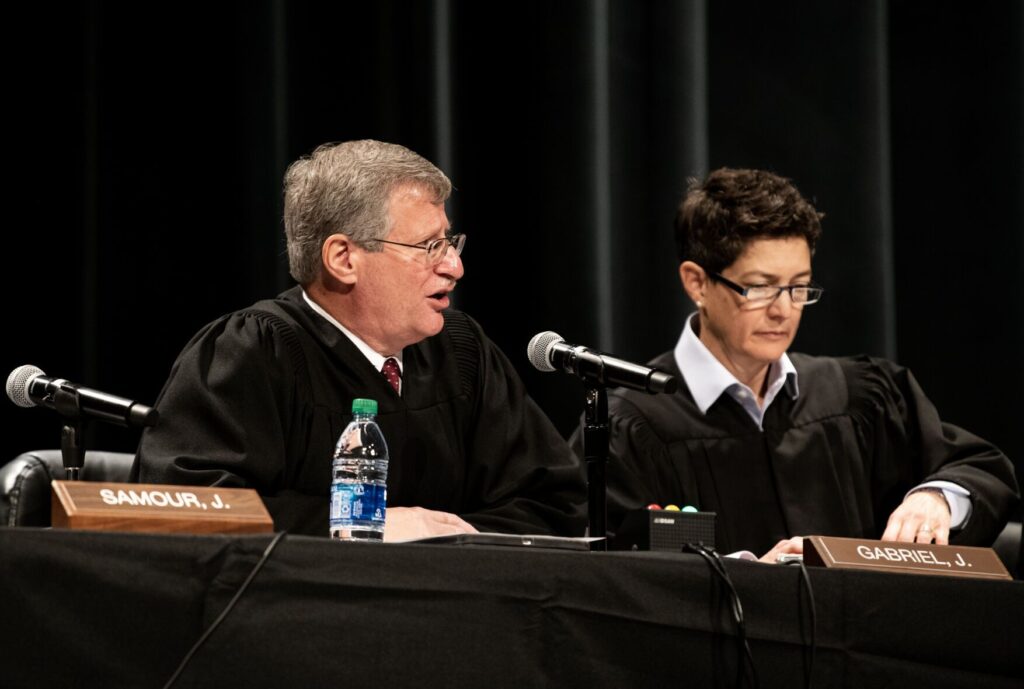

During oral arguments to the 10th Circuit last year, some members of the panel were sympathetic to the notion that departmental policy may require impoundment of personal items.

“Once you have the property of the arrestee, you take it on to the police department and store it there, absent some notarized permission for somebody else to take it. Why is that not a reasonable approach?” said Judge Harris L Hartz. “They should definitely not just leave it on the street.”

Moritz, on the other hand, tore into the government’s rationale for failing to recognize that turning the bag over to Gay was a viable alternative.

“The defendant and the girlfriend are apparently very fine with having the bag taken off with her. Who are they protecting at that point in the community?” she demanded.

“They’re protecting the defendant’s property,” said Assistant U.S. Attorney Wayne Paugh. “There’s a duty of care owed to the defendant -“

“If it’s his property and he says, ‘This is my girlfriend. Give it to her,’ how are they protecting the defendant’s property?” Moritz interjected. “The officer testified he was gonna take it regardless. How is that reasonable under this scenario, where a person is ready, willing and able to take it?”

The panel’s opinion confirmed that because a reasonable alternative to impounding the backpack existed – giving it to Gay – Carman had no justification to perform a warrantless inventory search. Moritz pointed out the “troubling” testimony from Carman that, even if he had turned over the backpack, he would have searched it first.

Regardless of Carman’s reasoning for his actions, “an illegal search would still have taken place,” Moritz noted.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office declined to comment on the ruling. A spokesperson for the Denver Police Department did not immediately answer whether Denver’s impoundment policies comply with the court’s holding.

The case is United States v. Braxton.