Colorado officials hunker down in search of a viable homeless strategy

City councilmembers are weighing dueling ideas as they consider steps to revamp Aurora’s homelessness program after trips to Texas, where they explored models for reducing this social woe that plagues metro Denver.

Denver has been struggling to address homelessness, which jumped by 12.8% – from 6,104 to 6,888 – from January 2020 to January this year. Local authorities have poured significant resources into tackling homelessness in the past few years.

Councilmembers, who also researched strategies closer to home, such as in Colorado Springs, diverge in their approach. Some prefer a “housing first” model, while others favor “treatment first.” The city could plausibly adopt a strategy that borrows from both models to create something specifically for Aurora.

Squatters take over a Colorado Springs home; now, the owner is in a homeless shelter

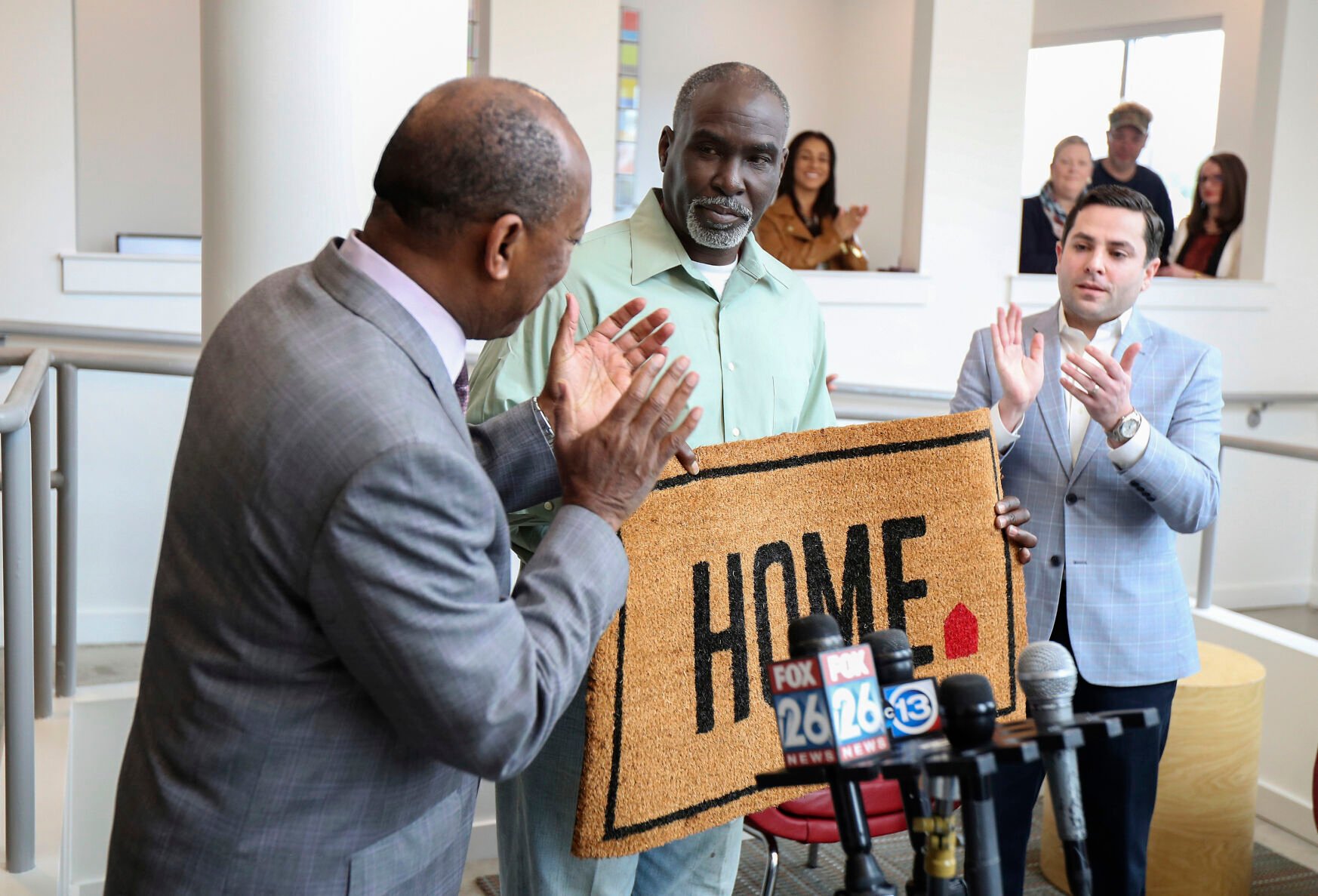

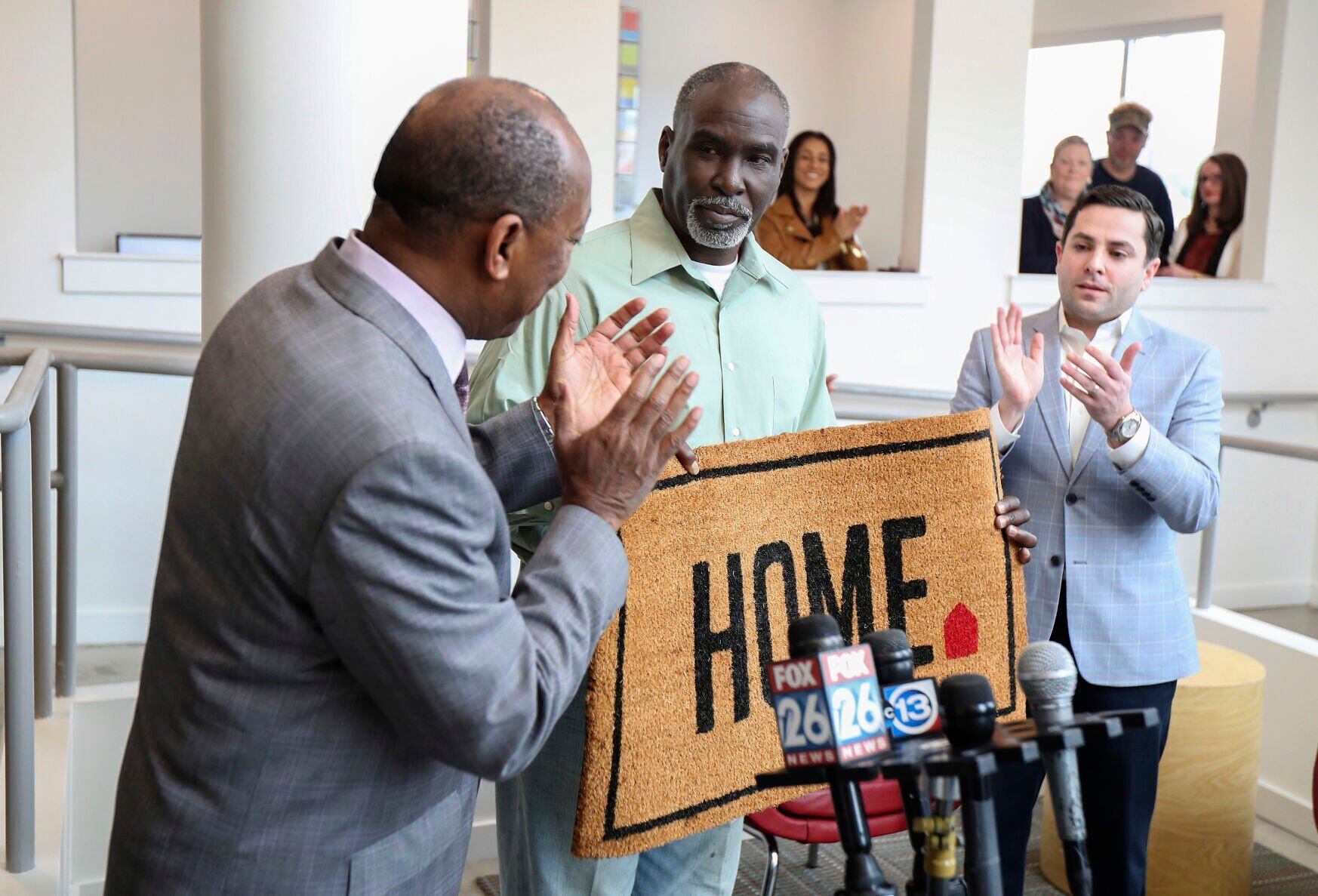

The trips began last month with councilmembers Juan Marcano, Alison Coombs and Mayor Mike Coffman, along with other metro Denver area representatives, visiting Houston to hear from its city leaders about “housing first.” Houston’s success has garnered national attention that, its leaders say, could serve as a national model for tackling homelessness.

Houston’s model provides people with permanent supportive housing, which combines housing with social services. Under this approach, resources, such as housing vouchers, are coupled with support services tailored to an individual’s needs.

Councilmember Dustin Zvonek, a critic of housing first models, helped organize a trip to San Antonio, eager to learn about alternative approaches, notably “treatment first,” such as the Texas city’s Haven for Hope, a campus that offers emergency shelter, transitional housing, case management services, and serves as the hub for numerous social services – from addiction treatment providers to job skills training.

The city officials’ impressions of their visits have already begun to form as foundation of arguments that will likely play out in the next several weeks and potentially shape the contours of Aurora’s next homelessness policy, which some describe as a “patchwork” system that fails to tackle the social woe’s underlying causes. Councilmembers expressed both attraction – and aversion – to what they encountered in Texas. Their ultimate challenge is to craft a policy that works for Aurora, taking into account the socioeconomic and political differences between one of metro Denver’s largest cities and the two Texas cities.

Zvonek, for one, dislikes the fact that the Haven for Hope campus has transitional housing right next to emergency shelter. He said that means homeless families could live nearby known sex offenders or people clearly reliant on substances.

“The emergency shelter, it’s very raw,” Zvonek said.

Zvonek believes “housing first” approaches work for a small percentage of homeless people – those who are truly unable to care for themselves. For most people, though, that’s not the case, he argued.

Colorado Springs’ new homelessness prevention coordinator is the city’s ear on issues

Zvonek favors requiring people who receive supportive housing and also struggle with an addiction to receive treatment. Providing them housing without that condition does not “change their condition,” he argued.

“You got them off of the street, but they are not on a path toward self-sufficiency,” he said.

It could take someone three months, 18 months or two years to progress from emergency shelter into permanent housing of their own, he said, adding each individual’s progress would go at a different pace.

“I don’t think there is anything humane about allowing somebody who could become self-sufficient to not,” he said.

Zvonek is preparing a presentation for the Aurora City Council about his vision for addressing homelessness. He does not want to exactly replicate any of the approaches the council has been researching, he said.

“We should look to build our own model,” he said.

Zvonek sees a comprehensive approach that includes the city’s camping ban, emergency shelter, transitional housing available with conditions, such as treatment requirements, and a navigation center with services, including mental health and addiction recovery services or job skill training.

Emergency shelter is necessary with a camping ban in place, Zvonek said, adding that’s a way to push people toward accepting city services.

The councilmember hopes Aurora lawmakers will approve a resolution before the end of the year directing city management to craft a new homelessness prevention model.

“I believe that, in the coming months, we will outline a strategy, a comprehensive strategy,” Zvonek said.

Mayor Pro Tem Francoise Bergan, who toured Springs Rescue Mission in Colorado Springs before joining the delegation to San Antonio, does not believe “housing first” models work as well as advocates say.

She favors strategies that incentivize participation in services, which she said is what she found in Colorado Springs.

“What I liked about their model is that they kind of have built in incentives to get people to move up the ladder, in terms of services,” she said.

Someone can come to the facility for a hot meal but is incentivized to access other services with rewards, such as additional menu options or a personal locker, she said. People who reach certain milestones can obtain permanent supportive housing, she said.

Bergan did not walk away from her visit in San Antonio completely sold on the city’s strategies because, she said, Haven for Hope does not believe in incentives. She also dislikes the idea of services without requirement, noting one example, in which a person had received housing services for 18 months at Haven for Hope but was not required to work.

“Intrinsically, that is actually much more compassionate, and for the person, (it) gives them pride and dignity,” she said.

Bergan found the courtyard area disturbing, she said. People were “strung out” throughout the section and clearly intoxicated on substances, she said. She saw one person with a bloody eye, and, later, when another man began loudly yelling, no one came to deescalate the situation, she said.

San Antonio “might as well have had them be homeless on the street,” she said, referring to people camping in the courtyard section.

Marcano, on the other hand, left San Antonio generally impressed by the campus and how the city formed it, calling the one-stop-shop a strong partnership among the city and area providers.

There are pitfalls, he said.

Despite the city gifting Haven for Hope land, the campus cost $100 million to construct and roughly $25 million annually to operate, he said.

“Although it’s impressive, it’s very expensive,” he said.

Like Zvonek and Bergan, Marcano does not want to replicate the entry courtyard space for emergency shelter on the Haven for Hope campus. He found the open camping, fencing, a concrete design and “anti-homeless” seating elements unappealing, calling it “especially strange.”

“It felt like a prison yard,” he said. “They acknowledge the architecture is hostile. The accommodations are fairly inhumane.”

Of the thousands Haven for Hope serves annually, about 20% are returning visitors, he noted. About 90% of people who graduate from Haven for Hope are still housed after one year, he added, noting that success rate dwindles faster than Houston’s, dropping to 80% at two years and 75% after three, and about 90% of Houston’s clients are still housed after two years.

Marcano said he thinks that any navigations centers stood up in the Denver metro area should mimic Haven for Hope’s consolidation of services. Navigation centers are not shelters, he said. Instead, he noted, they can provide bridge housing while people are connected with services and leasing agreements are arranged for them.

Marcano, an enthusiastic supporter of Houston’s approach, wants Aurora to implement a model prioritizing permanent, supportive housing. He hopes Aurora goes with a regional, “housing first” approach that relies on navigation centers in the metro area to connect people with services and housing, he said.

He argued that “housing first” is more fiscally responsible because it saves communities inordinate costs of managing homelessness instead of reducing it. His top goals, he said, include efficient spending and a humane approach to the difficult issue.

“I think Houston’s approach is that,” he said.

With councilmembers having visited Houston, San Antonio and Colorado Springs, Zvonek said “there were some clear commonalities” across all the models.

“The big one being that you have a comprehensive approach,” he said.

Zvonek and Bergan said federal funds come with more strings attached and they prefer a system that relies on private funding, as opposed to government dollars.

Federal funding can come with requirements to prioritize “housing first,” something the councilmembers do not want to feel forced into.

Zvonek’s frustration with Aurora’s approach is that it’s a patchwork system, he said, rooted in funding various nonprofits and emergency services, such as beds and meals, as opposed to addressing the causes of homelessness.

Both Zvonek and Bergan said a regional approach would be ideal, but they do not think it’s necessary, and that Aurora can forge its own path.

Marcano is now working to persuade minds to embrace a regional approach and generate council support for “housing first,” he said. Homelessness is a regional issue, and Aurora cannot make a real difference in curbing it unless regional jurisdictions work together, he said.

Aurora officials are planning to meet with the Denver City Council’s housing committee before the end of the year, which he hopes will ignite the potential for regional collaboration.

“I think we can make small gains in our city, but we will never address this issue if we try to go it alone,” he said, “because it is a regional issue.”