10th Circuit splits 2-1 on whether to order review of man’s torture claim

Even though the federal appeals court based in Denver acknowledged an immigration judge in Colorado made a mistake when finding a Mexican citizen could avoid torture simply by moving elsewhere, it declined to overturn a deportation order by a 2-1 decision on Monday.

Carlos E. Lockwood Alvarez asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit to review the federal government’s conclusion that he could not remain in the United States, citing the United Nations Convention Against Torture (CAT) and federal laws stemming from the nearly-40-year-old humanitarian treaty. An immigration judge decided Lockwood Alvarez did not meet the necessary conditions, despite being tortured twice by Mexican authorities after an earlier deportation.

The Board of Immigration Appeals upheld that decision, and the 10th Circuit agreed, determining Lockwood Alvarez had failed to show his past torture on multiple occasions meant there was a specific risk he would continue to be tortured.

“As he presented only generalized country conditions, the BIA did not err in affirming that Lockwood Alvarez failed to meet his burden to show a particularized risk of torture,” wrote Judge Allison H. Eid in an Aug. 1 order.

Judge Robert E. Bacharach indicated he would have ordered a fresh review, however, because the immigration judge held Lockwood Alvarez to an incorrect standard. While the CAT laws require an evaluation of whether someone can avoid torture by relocating elsewhere in the country, the judge reviewing Lockwood Alvarez’s case did not ask whether it would be difficult for him to relocate, but instead whether he was completely “foreclosed” from relocating.

Having a CAT applicant show that relocation is impossible to avoid torture, Bacharach pointed out, is not what the law requires.

“Had the Board considered this difficulty in relocating (rather than consider only whether relocation had been foreclosed), the Board might have come to a different decision when weighing the other evidence presented by Mr. Lockwood Alvarez,” he wrote in dissent.

A white family adopted Lockwood Alvarez from Mexico when he was six months old and brought him to live in the United States. According to his attorney, the family did not submit paperwork in time for Lockwood Alvarez’s 18th birthday and he never became a citizen.

He amassed a lengthy criminal record and the government eventually deported him to Mexico in 2011. While in Tijuana, police officers tortured Lockwood Alvarez. He escaped to Puerto Vallarta, nearly 1,400 miles away, only to be tortured again. Lockwood Alvarez contended his appearance, foreign mannerisms and lack of Spanish proficiency made him a target.

“Both incidents appear to have been kidnap-for-ransom attempts,” said his lawyer, James S. Lamb. “He was beaten, held against his will, and burned with cigarettes and apparently a metal rod or poker.”

Lockwood Alvarez then lived briefly with a U.S.-born pastor in a gated community. But he could not afford to live there permanently and had to move. Working as an electrician, Lockwood Alvarez had a client threaten his life, after which Lockwood Alvarez fled to the U.S. border and requested humanitarian protection in 2018.

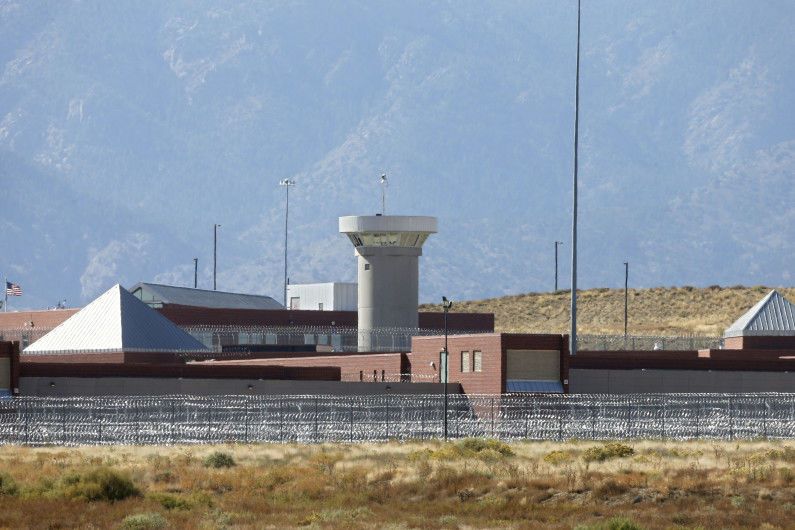

In June 2019, Lockwood Alvarez’s request for relief from deportation came before Elizabeth H. McGrail, an immigration judge working out of the Aurora detention facility. She found Lockwood Alvarez’s representation of his time in Mexico and his fears of returning to be credible, although she noted he had misrepresented and deflected on his criminal history.

McGrail decided Lockwood Alvarez’s criminal convictions made him ineligible for asylum, but also declined to halt his deportation under CAT. After his second kidnapping and torture, McGrail noted, Lockwood Alvarez was able to live “for at least two years” without being tortured again. Further, the evidence did not show why his torturers “would still seek to harm him in the future.”

Finally, she decided Lockwood Alvarez had been able to safely relocate in Mexico to avoid additional torture, and consequently he had not shown that “relocation is foreclosed.”

In a two-page decision upholding McGrail’s conclusions, Board of Immigration Appeals member Anne J. Greer agreed Lockwood Alvarez had not shown “it is more likely than not that he will face future harm” in Mexico, and that he was capable of moving to escape the threat of torture.

On appeal to the 10th Circuit, Lockwood Alvarez contended Greer and McGrail had played down his own experiences being tortured in determining whether he faced such a risk in the future.

“The situation might be different if the Immigration Judge had doubted Lockwood’s testimony or the government had successfully undercut Lockwood’s evidence with its own,” Lamb wrote to the court. “But in this case, Lockwood’s credible testimony and unchallenged evidence, taken together with the lack of any competing evidence from the government, should have been sufficient to establish ‘substantial grounds’ for believing Lockwood would be tortured in Mexico.”

During oral arguments before the 10th Circuit in 2020, some members of the panel pushed back on the notion that Lockwood Alvarez would not clearly face continued kidnapping or torture upon returning to Mexico, considering his mannerisms and appearance remain the same.

“It’s not that he doesn’t speak Spanish. It’s that when he walks down the road, he will be identified as ‘other’,” said Judge Jerome A. Holmes. “Why is that not good enough?”

“He lived there for seven years and he is providing us two instances only (of torture),” replied Raya Jarawan with the U.S. Department of Justice.

“I wonder if the immigration judge didn’t simply misunderstand the claim,” Bacharach interjected. “He’s saying because (he’s) anglicized, that will continue to differentiate him from everybody else in Mexico.”

The 10th Circuit’s decision ultimately agreed with the government that Lockwood Alvarez had not shown it was more likely than not he would continue to be tortured in Mexico. However, all three members of the panel sided with Lockwood Alvarez in finding he did not need to show it was impossible for him to relocate to avoid torture.

“To be clear, we agree that the (immigration judge) applied the wrong test when it stated that the possibility of relocation must be foreclosed or impossible,” Eid wrote for herself and Holmes. But, she continued, the review from the Board of Immigration Appeals reached the same conclusion as McGrail without applying the faulty standard, requiring the 10th Circuit to affirm the underlying order.

Bacharach disagreed. In his view, the review of McGrail’s findings should have been conducted anew based on the immigration judge’s mistake. The same information could have supported a conclusion that Lockwood Alvarez would face difficulty in relocating due to the inherent characteristics that made him a target.

“(W)e don’t know what the Board would have decided if it hadn’t relied on the immigration judge’s factual finding as to relocation,” Bacharach wrote.

Lamb, the attorney for Lockwood Alvarez, said his client is now back in Mexico, keeping “a low profile” and working in construction in an undisclosed location.

The case is Lockwood Alvarez v. Garland.