5 Colorado Native American boarding schools linked to Department of Interior report

A first-of-its-kind federal study of Native American boarding schools around the U.S. that for over a century sought to assimilate Indigenous children into white society has identified more than 500 student deaths at the institutions so far, but officials say that figure could grow exponentially as research continues.

The Interior Department report released Wednesday expands to more than 400 the number of schools that were known to have operated across the U.S. for 150 years, across 37 states (and former territories), including 21 schools in Alaska and seven schools in Hawaii.

According to the report, many of these schools were concentrated in the Southwest and the West, including Oklahoma, which had the most Indian boarding schools of any state with 76. Arizona had 47 and there were 43 discovered in New Mexico.

Burial sites found at 53 Native American boarding schools, U.S. government says

Colorado had five schools: Three were located off reservations and two on tribal lands.

The three boarding schools located off tribal land were the Teller Indian School in Grand Junction; Fort Lewis Indian School, which is now Fort Lewis College in Durango; and the Southern Ute Boarding School in Ignacio. The two schools on reservations were on Southern Ute land and on Northern Ute tribal grounds.

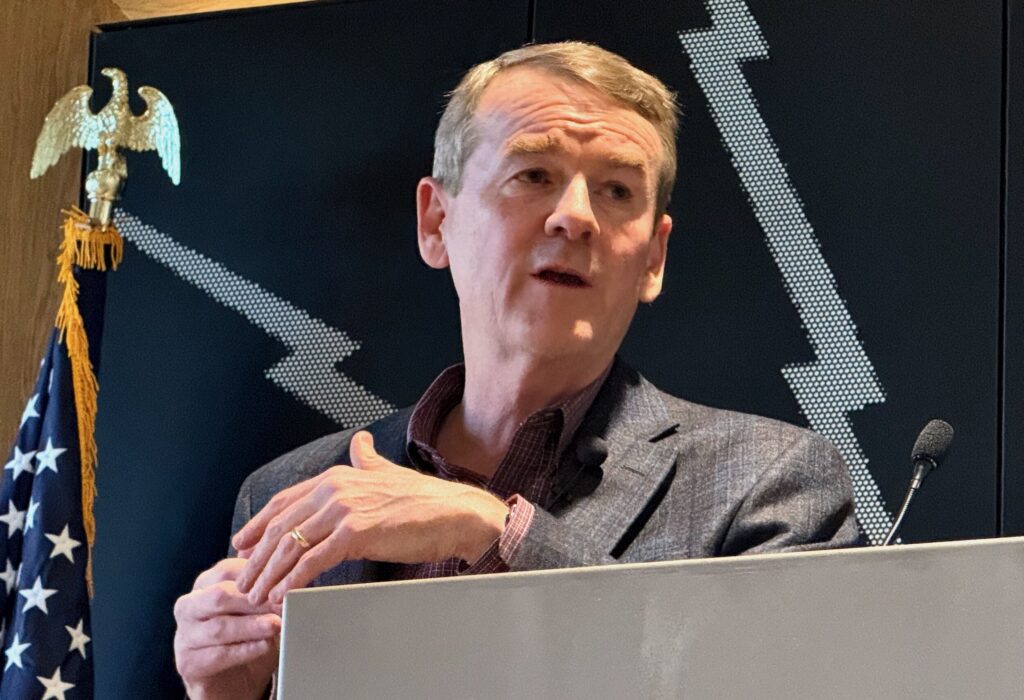

Colorado’s Indigenous leaders say the report lends huge credibility to what they already knew from stories passed down through generations. “It’s a hard conversation. I think it’s a historic day, because now we’re talking in earnest about one of the darkest chapters in our history,” said Ute Mountain Ute Tribal member Ernest House Jr.

He said he wondered if the report would lead to anything, and now that it has shown specific numbers of deaths, he expects for there to be more, because there’s so much information yet to be discovered.

Metropolitan State University of Denver to offer free tuition to Native, Indigenous students

His own father, Ernest House Sr., ran away from Ignacio Southern Ute boarding school where he was taken before he was 10 years old. House said his father’s getaway, running 50 miles on foot before he rejoined his family in Cortez, may have saved his life.

“He was able to survive. He reconnected with his family. So many other children didn’t make it or got caught,” said House. “My dad didn’t talk about it until later in his life. It’s reopening a deep wound for so many people.”

House Sr. was chairman of Colorado’s Ute Mountain Ute tribe for 35 years before he died in 2011.

House Jr. said that the reason most boarding schools were located off the reservation was because it was easier to assimilate Indigenous children by taking them away from their culture, “Physically removing children from the family is the fastest way to transition them. It came with cutting their hair, Westernizing them in time-period dress and uniforms, and taking away their language.”

Call for Pikes Peak to be renamed to its Ute name gains steam

Many children never returned home, and the Interior Department said that, with further investigation, the number of known student deaths could climb to the thousands or even tens of thousands. Officials say causes included illness, accidental injuries and abuse.

“Each of those children is a missing family member, a person who was not able to live out their purpose on this earth because they lost their lives as part of this terrible system,” said Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, whose paternal grandparents were sent to boarding school for several years as kids.

The agency – with the help of many Indigenous people who had to work through their own trauma and pain – has pored through tens of thousands of boxes containing millions of pages of records. But accounting for the number of deaths has been difficult, because records weren’t always kept.

In southwestern Colorado, Southern Ute leaders were meeting with the regional office of the U.S. Department of Interior to discuss the report Wednesday afternoon, so they did not have immediate comment on the groundbreaking report.

Colorado school district becomes 1st to drop Indian mascot since passage of law banning its use

It’s unknown how many Colorado Indigenous children died in the five state boarding houses, but researchers and archeologists have been studying the Colorado schools, looking for graves and combing obituaries to get as close to the truth as they can. Some deaths were covered up and others went unnoticed, so it may impossible to get an accurate number.

To find answers, the Colorado Legislature passed House Bill 1327, which establishes a Native American boarding school research program in the Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs. It’s awaiting Gov. Jared Polis’ signature.

Last September, House Jr., who is on the Board of Trustees at Fort Lewis College, ceremoniously pulled down plaques located on pillars outside the school that tell a glorified history of the Fort Lewis Indian School, which depicted the children who boarded there as “well-clothed and happy,” having received “extremely good literary instruction” while participating in enriching activities.

American Indian mascot lawsuit may be headed for quick decision

Originally an Army post, Fort Lewis was decommissioned in 1891 and transitioned into Fort Lewis Indian School, which lasted until 1911 in Hesperus. It moved to the Durango location and became a college in 1956.

The Interior Department report was prompted by the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves at former residential school sites in Canada that brought back painful memories for Indigenous communities.

Haaland also announced Wednesday a yearlong tour for Interior Department officials that will allow former boarding school students from Native American tribes, Alaska Native villages and Native Hawaiian communities to share their stories as part of a permanent oral history collection.

“It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies, but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous Peoples can continue to grow and heal,” she said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.