Collective bargaining draft bill strips out all public sector employees except for county workers

Apparently bowing to pressure from the state’s public college and university leaders, a bill that started with allowing collective bargaining for all public sector employees is now down to just one group: county workers.

A draft bill obtained by Colorado Politics shows public colleges and universities, which vigorously fought the measure, are no longer included in the bill.

And the counties are not happy to be the last group standing.

The bill, which House Majority Leader Rep. Daneya Esgar, D-Pueblo, and Senate President Steve Fenberg, D-Boulder, are expected to sponsor, could be introduced as soon as Friday, with its first committee hearing occurring on Monday, the 104th day of the 120-day session.

Esgar has worked for the last two sessions to mandate that public sector employees be allowed to unionize and engage in collective bargaining. As originally envisioned this year, the measure would apply to those who work in the K-12 and higher education sectors, counties, municipalities and special districts.

But over the past two months, that list has winnowed down, first striking out municipal and K-12 employees.

A version from March only counted counties and public colleges and universities.

Leaders from the two sectors, which have opposed the bill from the beginning, have argued for changes to define bargaining units very narrowly. Higher education representatives want to tie collective bargaining units to one per campus or even one for an entire system, rather than permitting many groups to collectively bargain.

Among the critics in the higher education sector is former Lt. Gov. Joe Garcia, a Democrat who is now president of the Colorado Community College System, and his efforts – and by other critics – appeared to have paid off. Their victory also means a big loss to unions, such as the American Federation of Teachers and American Association of University Professors, who have advocated for separate bargaining units for adjunct faculty, which make up the largest share of the teaching force at community colleges and a significant portion of faculty at four-year institutions.

Counties have sought a similar approach, preferring to define units as county-wide, rather than by individual departments, for example.

The latest draft, dated April 21, narrows just who in a county would become eligible to be in a bargaining unit. The draft specifically excludes employees in mass transit operated by a county; schools, including charters; special districts; and, public hospitals.

It also sets the minimum number of employees for each bargaining unit at 50. In theory, this means a small county with fewer than 100 employees could only have one bargaining unit.

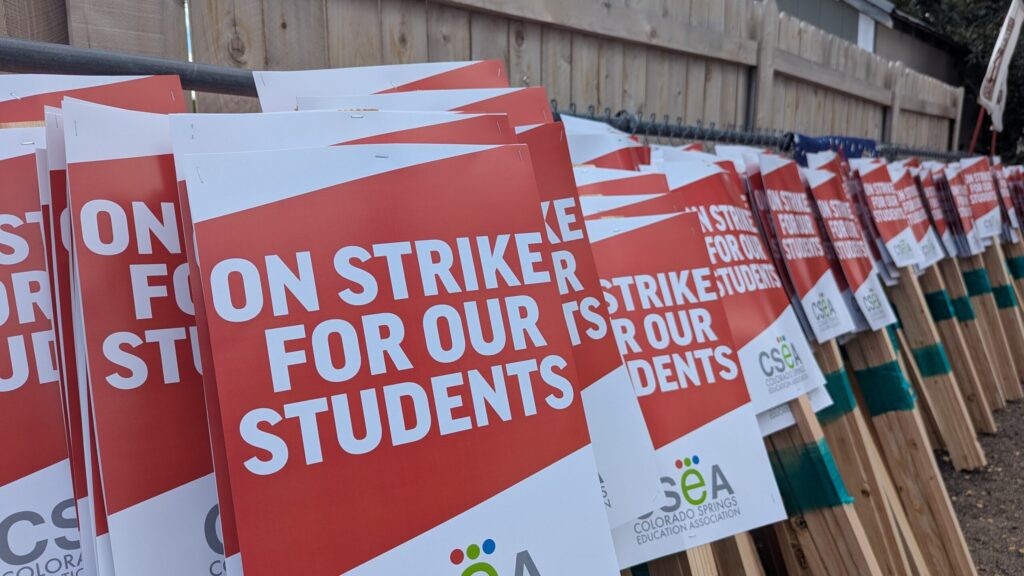

Another issue that divided bill sponsors and governmental entities opposed to the measure are strikes.

Under a 2021 law that allowed state employees to engage in collective bargaining, strikes are banned. Earlier versions of the 2022 collective bargaining bill were silent on the issue of strikes.

But the latest version, which includes language on strikes, work stoppages, slowdowns and sickouts, is unclear about who would authorize a strike. The draft says a certified exclusive representative, who would likely be a union leader, for example, “shall not threaten, facilitate, support or cause a county employee to participate” in a strike or work stoppage.

The draft doesn’t say the employees in a bargaining unit could not decide on their own to strike.

The other issue – and one that still irks counties – is the bill’s “unfunded mandate.”

A representative of Colorado Counties, Inc. told Colorado Politics that Pueblo County, which already has a collective bargaining agreement with its employees, estimated it would cost them $15 million to engage in wage negotiation. Jefferson County would need $17 million.

A Thursday news release from the counties’ trade group described the bill as a solution in search of a problem.

“Counties already can reach collective bargaining agreements with their employees,” the group said, noting that, in addition to Pueblo, the counties of Adams, Summit and Las Animas do have those agreements.

“But the decision to enter collective bargaining agreements is a complex local decision that should be left up to each local municipality and their county commissioners, local elected officials, and employees. Local employment matters that impact local economies is not the role of the General Assembly,” the group said.

The counties added that their share of costs ranges from a low of $150 million to as much as $400 million just to implement the bill, and more than $600 million annually in higher wages and benefits.

That would make the bill the largest unfunded mandate for counties in state history, the group said.

County commissioners from at least 10 counties plan to hold a news conference on Friday at the Capitol, where they will outline their arguments against the bill.

In a statement to Colorado Politics, Randi Weingarten, national president of the American Federation of Teachers, said the removal of higher education workers from the bill is a “missed opportunity to help the tens of thousands of Colorado faculty and staff struggling for a living wage, respect, and rights at work after years of repression and exploitation.”

“We are very disappointed – but at the same time we are glad that bargaining rights for local employees are moving forward,” Weingarten said.

Weingarten added that opponents to the bill “shamefully searched for every excuse in the book to avoid giving these workers a voice.”

“Six-figure earning college administrators distorted the facts about their schools’ financial standing, when the truth is they are sitting billions in unrestricted reserves-an amount that continues to grow by the day. And, sadly, this bill was also undercut by some elements of the labor movement, who reasoned that if the bill wasn’t perfect – and it wasn’t – or they weren’t going to benefit maximally, no one else should either,” he said.

Irene Mulvey, president of the American Association of University Professors, added that Colorado was poised to take “a giant step that would have improved public education and attracted the best and brightest faculty and graduate students to the state. Instead, by excluding higher ed from this bill, the message the state legislature is sending is loud and clear: faculty will be undervalued, overworked and exploited.”

She added: “Public employees in Colorado are entitled to a seat at the table and a meaningful voice in setting their working conditions. The AAUP stands firm in our commitment to collective bargaining rights for all academic workers in Colorado.”

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com