Colorado House committee advances bill that lowers felony threshold for fentanyl possession

A panel of Colorado legislators advanced a bill Wednesday that increases criminal penalties for possessing small amounts of fentanyl, a middle-of-the-road approach between factions who want harsher penalties and those who decry going back to the tough-on-crime strategy of the past.

The House Judiciary Committee advanced House Bill 1326, the legislature’s sweeping attempt to address the worsening fentanyl crisis, on an 8-3 vote. The committee’s approval came after more than three hours of debate and discussion Wednesday and hours of public testimony that began Tuesday afternoon and ended more than 13 hours later. The measure will now go to the House Appropriations Committee and, if approved there, to the entire House.

Much of the hours-long debate of the past two days focused on something that wasn’t in the initial draft of the bill: making it a felony to possess fewer than 4 grams of a substance containing fentanyl. Three different lawmakers on the Judiciary Committee tried to amend the bill to lower that amount: Rep. Terri Carver sought to make it a felony to possess any amount of the drug, and when that failed, Rep. Rod Bockenfeld proposed making it a felony for have more than a quarter of a gram. That, too, went nowhere.

House Speaker Alec Garnett – one of the bill’s sponsors – advocated setting the felony threshold at 1 gram. He couched it as a compromise between two diametrically opposed camps and one he felt wouldn’t ensnare people with substance-use disorders who take fentanyl, knowingly or otherwise.

In addition to the change in possession laws, the bill would also strengthen criminal penalties for possessing any amount of a fentanyl mixture with intent to distribute, with an additional charge when someone dies from ingesting that substance. It also includes $20 million to buy Naloxone. In addition, it establishes a new fund to purchase strips to test substances for the presence of fentanyl, directs the creation of a statewide education program and requires jails receiving certain state funding develop “protocols” for a key treatment option.

The committee also adopted an amendment that would make possession of a substance that’s at least 60% fentanyl a felony. But that amendment, even if included in the final version of the bill, would have little immediate effect. Garnett, who advocated for its inclusion, said the technology needed to test substances to that degree is not yet available in Colorado. The amendment, if the bill’s current version is enacted into law, would only take effect when that technological gap is bridged in the state.

Despite the breadth of the provisions in the bill, it was the possession issue that dominated Wednesday’s debate and the 13 hours of public comment that preceded it, a hyper focus that Garnett lamented.

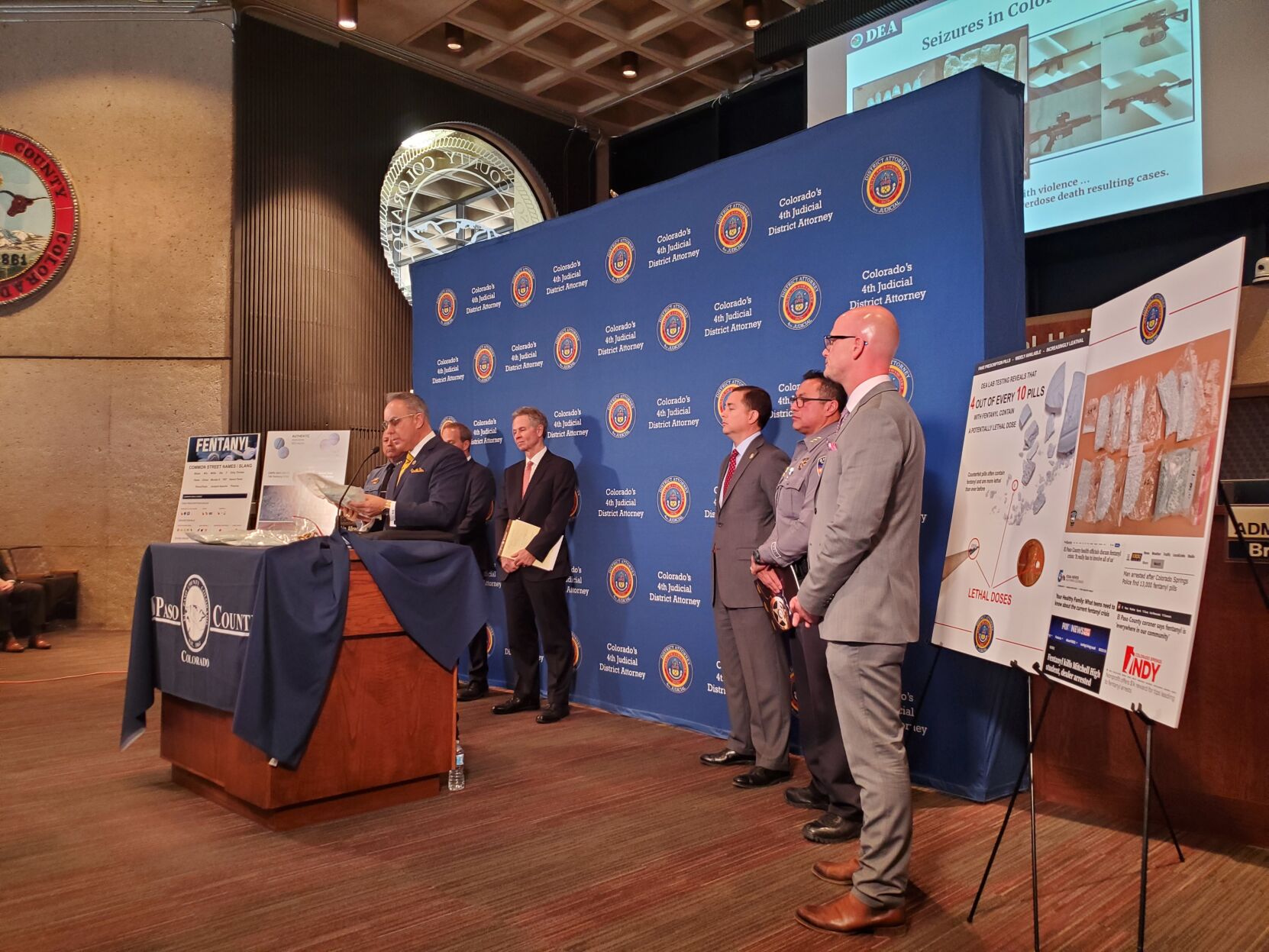

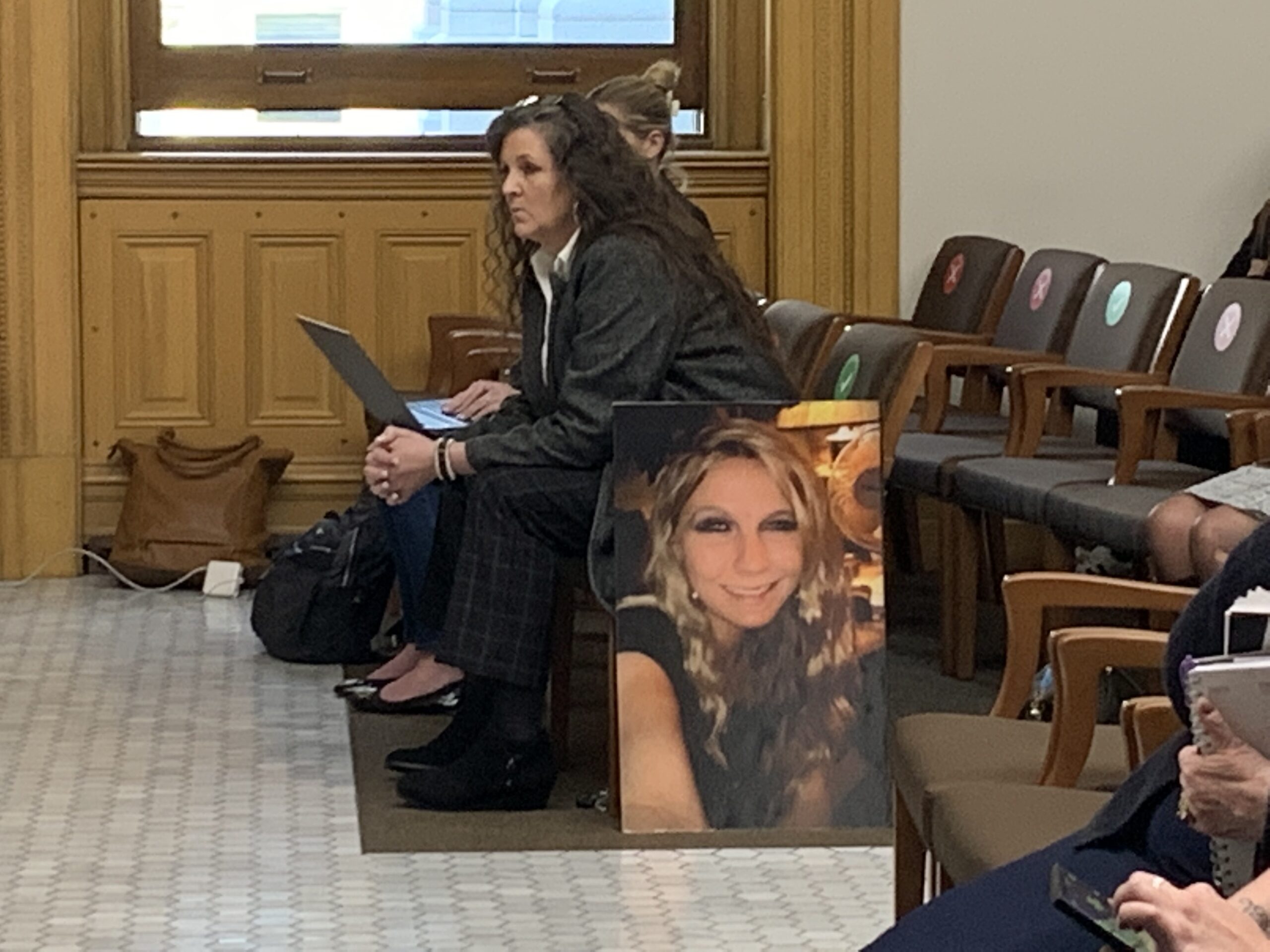

Law enforcement officials and district attorneys took turns Tuesday calling on lawmakers to make possession of any amount of fentanyl a felony. They were often followed, by design, by public health officials and harm-reduction experts who sharply criticized additional incarceration measures, arguing there’s no evidence to show they would help the state address its fentanyl crisis.

For several lawmakers, much of that debate turned on two interlocking issues. The first is the legislature’s previous efforts to decriminalize low levels of drug possession for most substances. Notably, a 2019 law made it a misdemeanor to possess up to 4 grams of many drugs, including fentanyl.

The second is fentanyl’s unique nature: A potent synthetic opioid used legitimately in medicine, the substance is mixed illicitly into other drugs, such as meth and cocaine, and is primarily found in pills often made to look like legitimate oxycodone tablets. Those pills are rarely pure fentanyl, officials in Colorado and elsewhere have said. Often, they have relatively low amounts of fentanyl and are primarily composed of other substances, such as the active ingredient in Tylenol. Still, because fentanyl is so potent at low doses, the pills remain deadly.

Those two issues collided Wednesday as Carver argued that possession of any amount of fentanyl should be a felony. She told the rest of the committee that a zero-tolerance approach would reflect the “lethality” of the drug. But Rep. Kerry Tipper, the committee’s vice chair, said changing the law in that manner would limit plea agreements because there would be no fentanyl-related misdemeanor charge to fall back upon.

Tipper referred to testimony given Tuesday by Josh Barocas, a physician and associate professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, who said he hadn’t seen a drug test that didn’t test positive for fentanyl in the past six years. Because fentanyl is increasingly mixed into other substances, Barocas and others said, “felonizing” any possession of fentanyl would de facto “felonize” small amounts of other drugs, too.

“That’s not what I was sent here to do,” Tipper told Carver, “and I don’t think it meets the moment we’re in.”

Rep. Mike Weissman, the committee’s chairman, agreed. He referenced two friends who, because of personal trauma they’d experienced, struggled with substance use. He wondered what would’ve happened to them had they been arrested while possessing a substance containing fentanyl and then faced a felony charge. He called Carver’s proposal “an extreme response and a harmful one.”

Bockenfeld tried next, attempting to make possession of a quarter of a gram of fentanyl a felony. Calling it a “life or death” issue, he referred to the number of people who could die from a quarter of a gram of pure fentanyl.

“I’m tremendously frustrated that the previous amendment lowering it down to zero did not pass,” he said, referencing Carver’s effort. “But I think it’s important we try to save as many lives as we can.”

But other lawmakers quickly pointed out that pure fentanyl is rare on the streets, citing testimony from law enforcement on Tuesday night. It’s most often found in pills, which Garnett said generally contain a 10th of a gram of fentanyl. The rest is “filler,” as Denver District Attorney Beth McCann described it Tuesday.

Tipper said she felt like she was “slamming my head against a wall” because she had to keep pointing out that fentanyl pills are not pure fentanyl, and, as a result, can’t kill hundreds of people. She said lawmakers aren’t “operating in reality if that’s what we’re legislating to.” She later said that anyone advancing that narrative is either uninformed or intentionally misleading the public.

Garnett said 1 gram of fentanyl – the felony limit he prefers – is more in line with personal use.

“I just want to be very thoughtful about this discussion,” he said, “because it incorporates challenges of fentanyl because, in its purest form, it’s very deadly. However, on the street, that’s not how we’re finding it.”

Like Carver’s before it, Bockenfeld’s quarter-of-a-gram proposal failed. Lawmakers then voted to advance Garnett’s proposal, setting the misdemeanor limit of fentanyl possession at 1 gram and making it a felony, with varying degrees of incarceration attached, all weights above it. The amendment also requires that users know or should have known that the substance they are caught with contained fentanyl.

Weissman, who voted against every attempt to change the law around fentanyl possession, then put forward two amendments to more quickly seal the records of people convicted of the newly proposal felony charge and to allow those same people to vote while in jail. Both passed.

With amendments finished, lawmakers then voted, 8-3, with Lock, Bockenfeld and Carver voting “no,” to send the bill to the House Appropriations Committee. Carver said she doesn’t think the new felony levels “would do much of anything.” Bockenfeld said the 1 gram level “wasn’t a good compromise” and that the bill, to his mind, “didn’t accomplish what it was meant to accomplish, which is to save lives.”

Garnett acknowledged that the bill isn’t perfect and that it is just the beginning of the state’s response to the crisis. But he indicated that not enough people had paid attention to the harm reduction and education pieces of the bill and that, he thought, overall, the measure is a “monumental step forward.”

Rep. Mike Lynch, who co-sponsored the measure with Garnett and others, implored lawmakers to advance the bill and address the fentanyl crisis.

“We’re seeing it take over our state,” he said of the drug. “We’re seeing it get into very single drug out there, and for us to not act would be a complete dereliction of our duty.”

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com