State Supreme Court declines to give Weld County prosecutors another chance to argue for unlawful seizure

There was little truth to Weld County prosecutors’ claim that a trial judge failed to give them the opportunity to defend a warrantless police seizure, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Monday.

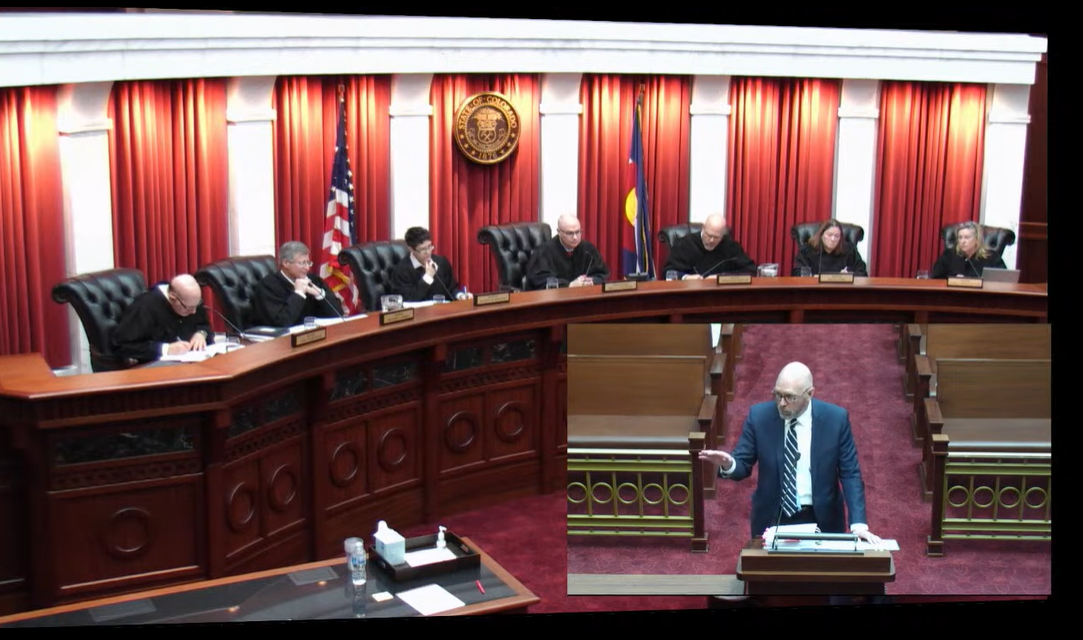

The justices unceremoniously swatted away an appeal from the Weld County District Attorney’s Office in an unusual unsigned opinion. The appeal arose after District Court Judge Marcelo A. Kopcow suppressed evidence found on a suspect’s cell phone as part of a child pornography investigation. The prosecution alleged they should have another opportunity to offer evidence and arguments in defense of a Greeley detective’s decision to snatch the cell phone.

In reality, the court said in a terse, four-page decision, the district attorney’s office had ample time to show why the seizure did not amount to a Fourth Amendment violation, given that Kopcow and the defense repeatedly raised the subject in the presence of prosecutors.

“We will not reverse and remand to the trial court to allow the People to make additional arguments that they declined to make when initially asked by the court,” the justices wrote.

Greeley Detective Dave Arpin received a tip in July 2019 from an anonymous informant who stated that he or she had seen naked images of girls on Joe Ramos’ cell phone. Arpin then learned that Ramos had two active warrants and was at the address that the informant, later identified as Ramos’ ex-girlfriend, provided.

When Arpin and officers arrived at the residence, they went to the backyard where they saw two men who matched Ramos’ description. Arpin called out to them, but the men entered the residence and refused to answer the door. While they intended to arrest Ramos for his warrants, officers spied cell phones on a table in the yard. Arpin called a number he had listed for Ramos and one of the phones rang.

Arpin took the phone and left his business card in its place. Ten months later, in May 2020, a judge approved a warrant to search the phone. Police reportedly found child pornography in several files on the phone.

Prosecutors filed 13 charges against Ramos related to the sexual exploitation and assault of children, all of which were felonies. In response, Ramos moved to suppress evidence from the phone, claiming Arpin retrieved it in violation of the Fourth Amendment’s general prohibition on warrantless searches and seizures.

Kopcow held a hearing in November and December 2021 to consider various motions in the case. The issue of suppression arose at multiple points.

“I think it makes sense for the Court to hear the evidence from the People relating to the suppression motion,” the prosecutor said. The defense also questioned Arpin in detail about the warrantless seizure.

After hearing the evidence, Kopcow told the prosecution that “the biggest issue that I have is the seizure of the cellphone. Everything else I – I could probably rule on today. I’m just not sure what the prosecution’s theory is for obtaining the cellphone and whether they are arguing – I’m not sure exactly what the argument is going to be.”

The parties then filed written briefs, in which the prosecution touched on the phone seizure. Kopcow ended up granting the defense’s motion to suppress, noting that Arpin’s actions were presumed to be unreasonable under the Fourth Amendment. When courts find that police have conducted an unlawful search or seizure, the general consequence is to exclude at trial the evidence stemming from the search, unless an exception to the warrant requirement applies.

Although the prosecution could attempt to justify Arpin’s warrantless seizure, the district attorney’s office, Kopcow wrote, “has failed to overcome this presumption and has offered no credible evidence in support of a recognized exception.”

The district attorney’s office turned directly to the Supreme Court, as is the procedure when prosecutors challenge suppression orders in interlocutory – or mid-case – appeals. Deputy District Attorney Arynn E. Clark complained that the defense had not made the prosecution aware of what it was arguing about the cell phone seizure, despite the title of the motion being “Motion to Suppress Evidence.”

“Because the issue was not properly raised by the defendant, the People were not on notice of the issue and therefore were not provided sufficient opportunity to present evidence and argument,” Clark wrote to the Supreme Court. “Thus, the District Court, prior to suppressing the defendant’s cell phone must provide the People with an opportunity to present additional evidence and argument.”

The public defender’s office countered that the prosecution knew before, during and after the trial court hearing that the exclusion of phone evidence was an issue.

The Supreme Court flatly rejected the idea that the district attorney’s office had insufficient notice that they needed to justify the warrantless seizure to the trial court or risk the exclusion of evidence.

“Indeed, six days after the court stated that it did not understand the People’s theory for obtaining the cell phone, the People submitted a brief addressing Ramos’s motions to suppress. That brief specifically discussed the seizure of Ramos’s cell phone, contending that it was justified based on the informant’s tip and the officers’ lawful presence in Ramos’s backyard,” the court wrote. “The People, thus, had an opportunity to raise any relevant arguments.”

The court upheld Kopcow’s suppression order. The case is People v. Ramos.