Denver officials announce public safety plan for 2022, citing violent crime increases

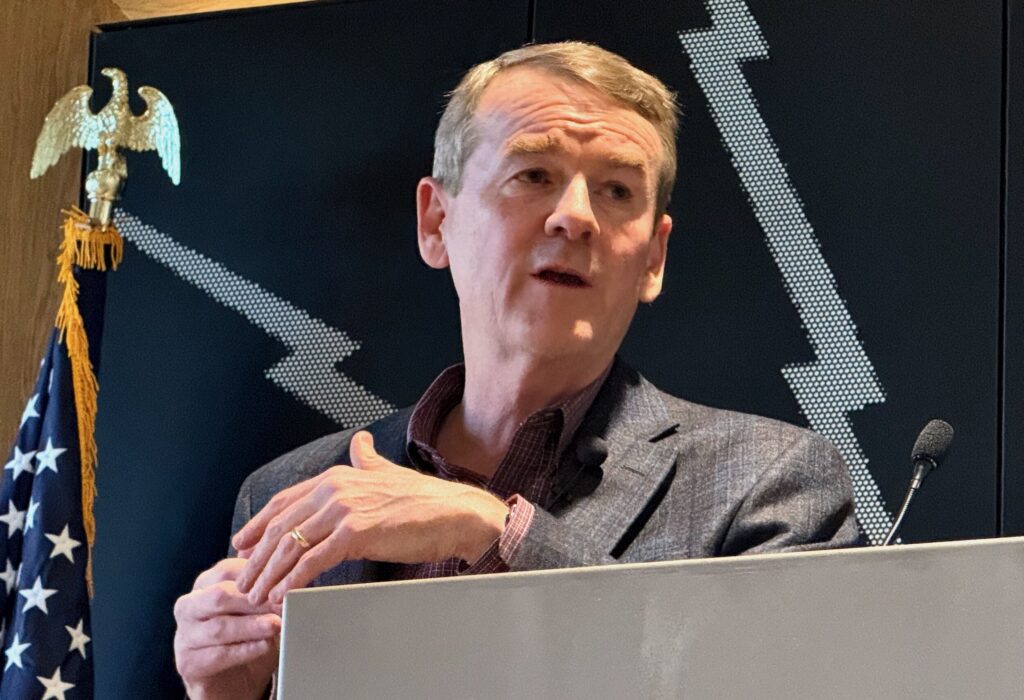

Mayor Michael Hancock has unveiled a multipronged initiative that he says should improve the city’s public safety through collaboration between local, state and federal agencies in response to increases in Denver’s violent crime rates.

Hancock and the city’s public safety leaders unveiled their plan during a news conference Thursday morning.

Of particular concern to Denver police are homicides, robberies and crimes that tend to be linked to the commission of other offenses, such as car thefts and people illegally possessing guns. The city tallied 96 homicides in 2021, excluding fatal shootings by officers, and 95 in 2020.

Mayor Hancock unveils plan to address rising crime in Denver

Officials said crime increases in Denver and across the country haven’t happened because of any single contributor, but “there is a broad agreement among experts” that the COVID-19 pandemic, increased number of illegal guns, social unrest and the opioid crisis have contributed to the problem, according to an outline of the plan.

“We have to identify these areas within our city where a disproportionate amount of crime is taking place and work in collaboration with the community to keep the people of Denver safe,” said Police Chief Paul Pazen in a news conference.

Some of the actions the city plans to take include expanding its “hot spot”- based policing, enforcement against illegal gun possession, creating a criminal charges filing team in the Denver Sheriff’s Department and developing and reviewing the city’s criminal bond schedule.

These initiatives will rely on other agencies besides the Denver Police Department. For example, reviewing the bond schedule will take coordination between the courts, public defenders, district attorneys and the sheriff’s department

The city also plans to add 144 new officer recruits and another 40 lateral officers this year.

People who possess guns illegally, especially because of prior felony convictions, have been a particular frustration for Pazen because of the tendency to use them in committing other crimes. By November last year, Denver police had seized about 500 more illegally possessed guns – over 2,000 — than the three-year baseline, he said in an interview last month.

“I thought 2019 was going to be our high-water mark in this, and we’ve exceeded that,” he said.

“The outcomes that we are seeing is people that are losing their lives, families that are losing loved ones, and that’s not okay.”

Homicides in Denver: Nearly half of all recent arrests tied to person under supervision

Police announced a plan last spring they termed collaborative policing to target five “hot spots” in the city they say make up a disproportionate share of homicides and shootings, a combination of increased patrols and working with community organizations for solutions to root causes of crime. The city plans to expand into three additional areas, Pazen said Thursday.

But the strategy has already created controversy. Critics have said the strategy leads to excessive policing of people of color and of behaviors driven largely by poverty, and some academics say simply increasing police enforcement in high-crime areas doesn’t show evidence of reducing crime.

Pazen said in a presentation to a City Council committee last summer that one spot at Holly Street and Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard had not had shootings by early August. But at the time District 9 Councilmember Candi CdeBaca pushed back on Pazen’s use of that metric as an indicator the police department’s collaborative policing strategy is working, since the city announced its launch in May.

“So for five months [in 2021] we didn’t technically have the program, but you’re attributing the lack of shootings at MLK and Holly that technically didn’t exist until May?” she said.

“I am disappointed to see us returning to the failed policies and practices that the global George Floyd protests were demanding cities move away from,” said Dr. Robert Davis, the head of Denver’s task force for Reimagining Policing and Public Safety, in a text message. Last spring the task force released a report with recommendations for decriminalizing behaviors that are linked to poverty and behavioral health, and similarly reducing the role of police in situations that would be suited for social services by focusing on responses from community-based specialists and service providers.

Sheriff’s body cam video reveals first hours of Suzanne Morphew mystery

“The Task Force gave Denver a roadmap to improving safety, but it appears Mayor Hancock and his Department of Safety have chosen political expediency over community solutions.”

Hancock’s plan also does include resources for behavioral health and alternatives to police response that include establishing an Assessment Intake Diversion Center to connect people in need of mental health and drug addiction services with resources rather than booking them into jail, and a crisis response team within the sheriff’s department specializing in mental health crises.

Denver’s newly nominated public safety director, Armando Saldate, said last month he believes reducing crime should be about bringing the right resources to situations to address underlying causes, such as trying to get people help for mental health or substance abuse issues that may be linked to public disorder crimes. Drug addiction and harm reduction highlight “the intersection of public safety and health,” Saldate said.

“I think it’s time we take the public health lens to the work that we do in public safety. … We know we aren’t going to arrest our way out of this problem, and that’s something you’ll probably hear from me often.”