Adams County prosecutors disregarded medical marijuana law in revoking probation, appeals court says

Prosecutors in Adams County were responsible for revoking a woman’s probationary sentence because she was using medical marijuana, even though the law allowed her to do so, the state’s Court of Appeals determined.

A three-judge panel for the appeals court was concerned that prosecutors had operated with an ulterior motive. Although the district attorney’s office and probation officials claimed Cynthia Marie Vigil violated the terms of her supervision because of missed drug tests and had a two-year-old alcohol violation, in reality, the government seemed focused on getting a judge to say whether medical marijuana use was grounds to return a person to custody.

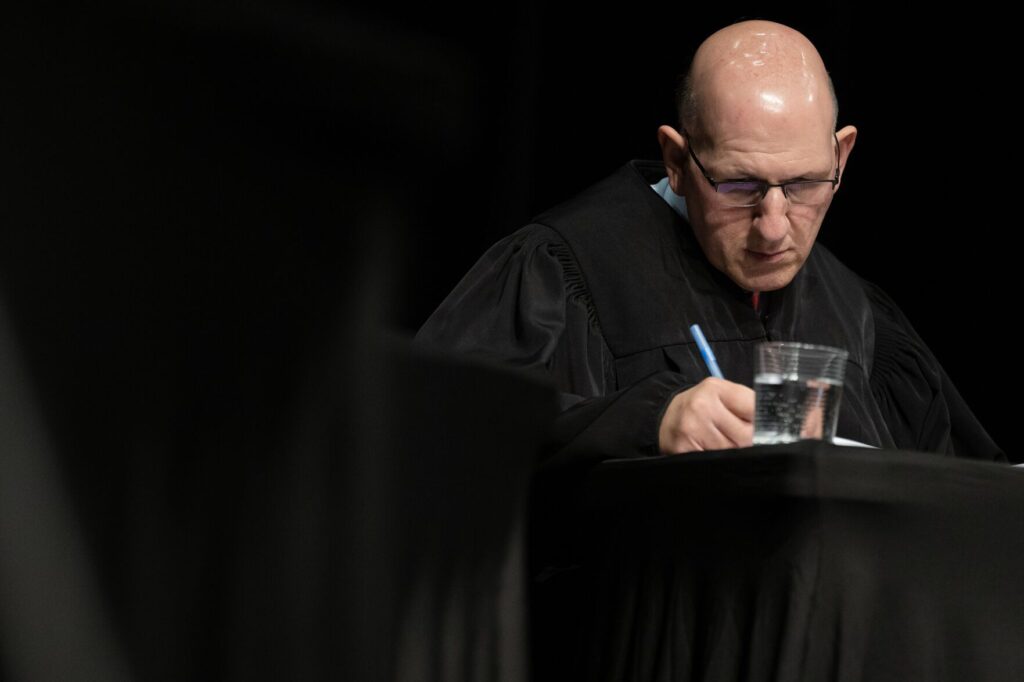

“It’s clear from the record that Vigil’s medical marijuana use was the main factor underlying the probation department and district attorney’s decision to seek revocation,” wrote Judge W. Eric Kuhn in the Jan. 13 opinion. “Under the particular circumstances of this case, we hold it was fundamentally unfair to seek revocation of Vigil’s [supervision] to obtain direction from the court on how to address medical marijuana for those on probation.”

In 2015, a jury could not form a consensus on the charge of reckless manslaughter against Vigil. Afterward, Vigil reached an agreement with prosecutors: she would plead guilty to attempted reckless manslaughter and assault. As a result, she would receive a four-year deferred judgment and sentence.

The DJS, as the Court of Appeals called it, subjected her to the supervision of the probation department. She had to abide by the terms of probation, including submitting to drug and alcohol testing and refrain from using alcohol. If she successfully completed the DJS, the court would withdraw the guilty plea and dismiss the charges. If Vigil violated the terms, she would serve the remaining sentence in custody.

Three years after the plea, the probation department alleged that Vigil violated the terms of her supervision by testing positive for alcohol and marijuana and missing 14 drug tests. Prosecutors asked a judge to revoke the deferred sentence in late 2018.

According to the Court of Appeals’ narrative, a point of “significant confusion” during her supervision was whether using medical marijuana was a violation of the probationary terms. The DJS agreement itself was silent on the subject.

Shortly after beginning her deferred sentence, a supervisor with the probation department determined she had a valid medical marijuana card. However, Vigil’s probation officer began hearing that the 17th Judicial District Attorney’s Office did not believe medical marijuana was acceptable under DJS agreements. When a new prosecutor took over Vigil’s case, she suggested the probation officer seek to end Vigil’s probation.

“Medical Marijuana seems to be the pressing issue and probation is respectfully seeking direction from the court in this matter,” the probation department subsequently wrote in its report to the court.

The matter culminated in then-District Court Judge Tomee Crespin revoking Vigil’s DJS and sentencing her to two years in community corrections, meaning a residential supervision program outside of prison.

Tristan Gorman, legislative policy coordinator with the Colorado Criminal Defense Bar, said it appeared Vigil was doing things correctly from her perspective, and it was the district attorney’s duty to show that barring Vigil from using medical marijuana was necessary to accomplish the goals of sentencing.

“When we’re in court, I hear a lot of judges describe a deferred judgment and sentence to defendants as, ‘This is a contract between you and the district attorney’,” Gorman said. “And it is inherently unfair to make an agreement between the parties where the defendant – who is obviously less educated, less experienced and less informed about the ways in which the court system works – to put on them this burden that a particular term or condition can change.”

The Court of Appeals quickly determined that Colorado law does not consider use of medical marijuana a violation of the terms of a person’s probation. The law also states that courts “shall not, as a condition of probation, prohibit the possession or use of medical marijuana,” unless an exception applies.

“By unilaterally and incorrectly prohibiting her from using medical marijuana,” Kuhn wrote for the panel, “the probation department and district attorney unlawfully added a condition to her DJS and improperly exercised their discretion to seek revocation based on that condition.”

The Colorado Attorney General’s Office denied that the medical marijuana use was the reason for revoking Vigil’s supervision. Prosecutors represented to the Court of Appeals that Vigil’s probation officer did not immediately act on the older alcohol violation, but instead “waited to seek revocation until the defendant had committed so many violations” that it presented a problem.

The Court of Appeals, however, did not find the government’s explanation credible.

Kuhn noted that the probation department admitted it was trying to “seek direction” from the court about whether medical marijuana use was grounds to revoke a deferred sentence. If prosecutors wanted to bar Vigil from using medical marijuana, Kuhn added, the proper way was to follow the law and “not to seek an advisory opinion.”

The panel sent the case back to the district court for a new hearing.

Gorman agreed with the Court of Appeals’ reasoning that Vigil’s probation officer might not have sought to rescind Vigil’s DJS if the only marks against her were the old alcohol violation and drug tests.

“Had it not been for the district attorney’s office policy change on medical marijuana, there probably never would have been a complaint to revoke this deferred judgment in the first place,” she said.

The 17th Judicial District Attorney’s Office had no comment as of Tuesday morning.

The case is People v. Vigil.