Jeffco sex assault conviction reversed after appeals court says judge allowed expert to vouch for victim

The state Court of Appeals reversed a man’s sexual assault conviction from Jefferson County after finding the trial judge allowed an expert witness who had not met the victim to essentially tell the jury she was being truthful.

In the 2018 trial of Steven Matthew Ramirez, Jeffco prosecutors called a “cold” expert to testify – so named because such experts know little about the actual case but can provide the jury with knowledge about a particular subject. The prosecution’s expert spoke to why children can delay reporting their sexual abuse.

Afterward, the jury submitted a question to the witness, asking if she had seen children fabricate stories of sexual abuse.

Then-District Court Judge Margie L. Enquist immediately put the question to the witness, who responded: “I don’t see children to screen out whether or not sexual abuse has occurred. That’s a job for forensic interviewers and the investigative team. So I see children who have already been through an investigative process and come to me after that has happened and it’s been determined to be what they call founded.”

On appeal, Ramirez claimed the judge should not have allowed the expert to answer because doing so vouched for the truthfulness of his accuser. Ramirez’s charges stemmed from a series of alleged sexual assaults in which his accuser, a child, was the only witness. Considering that the jury had also heard from the victim’s forensic interviewer, jurors could logically infer from the expert’s response that the accusations were “founded.”

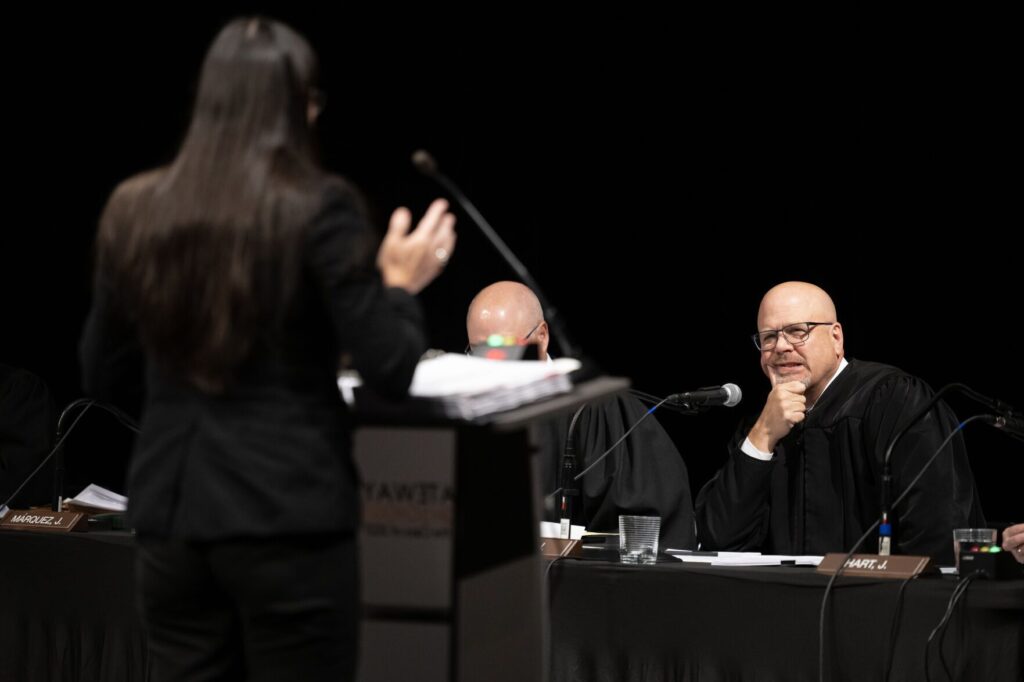

A three-member panel for the Court of Appeals agreed with Ramirez. The expert, wrote Judge Jerry N. Jones, “said, in essence, that if a child’s allegation has been ‘screened’ by a forensic interviewer and additional investigation and determined to be founded, it had not been ‘made up’.”

Jones also cited prohibitions from Colorado caselaw against witnesses testifying about the truthfulness of other witnesses and against implications that the use of a screening process means the person must be guilty if they ended up being charged.

Because the evidence of Ramirez’s guilt revolved around the story of his accuser, the panel found the expert’s suggestion on the witness stand that the accuser’s story was credible may have contributed to the jury’s verdict.

The appeals panel reversed Ramirez’s conviction for sexual assault and overturned another conviction for indecent exposure. The government acknowledged the statute of limitations barred his conviction for the latter offense.

The case is People v. Ramirez.