December economic forecasts show the pandemic still affecting state economy

The COVID-19 pandemic “remains in the driver seat” for Colorado’s economic outlook, according to economic and revenue forecasts presented to the Joint Budget Committee Friday.

That’s raising concerns about labor force participation, inflation and the impact on state spending.

Still, Colorado’s economy continues to recover, Legislative Council economists said, including a continued decline in the unemployment rate, which fell to 5.4% in October. That translates into the state regaining 83.3% of the jobs lost since the pandemic started, according to the Legislative Council presentation.

But that isn’t the whole picture when it comes to the Colorado employment situation.

Chief Economist Kate Watkins noted the jobs that haven’t come back are part-time, often held by low-income wage earners who work multiple jobs to make ends meet.

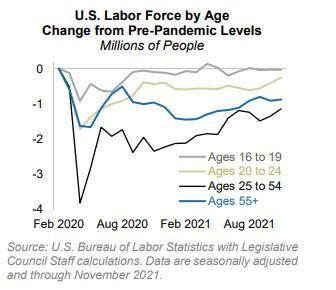

While Colorado doesn’t track that kind of data, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics does, and a chart in the Colorado forecast showed just how that labor participation has changed.

The job losses persist in the accommodation and food services sectors, which are still 16,200 jobs below pre-recession levels.

Watkins told JBC member that health considerations continue to keep people on the sidelines. But there’s also a psychological shift, she said: people are thinking about the number of hours they’re working and work-life balance. The pandemic has “challenged people’s thinking about employment and I think that will last.”

Inflation is also now a growing concern and a risk to the forecast, economists said. For 2021, inflation in Colorado is projected to be at 3.7%. Watkins said the continued pandemic and supply chain disruptions could result in higher inflation pressures. That has near-term impacts on the budget, Watkins explained, in areas such as school finance, construction costs and employee compensation.

Despite those pressures, the state is still expected to be in a TABOR surplus situation for the forecast period, with a $1.8 billion annual surplus over the next two years that will be refunded to taxpayers in the years following each surplus.

The upside to these pressures, according to economists: passage of President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better package, which could drive positive signs for spending, employment, income and tax revenue.

The gap between low- and high-wage earners troubled Sen. Chris Hansen, D-Denver, who pointed to the continued lag in the “k-shaped” economic recovery. That’s when different parts of the economy recover at different times. Colorado’s employment growth has continued to improve, but only for high-wage earners, defined as those earning $60,000 per year or more. Employment for low-wage earners, defined at under $27,000 per year, has fallen by 30.5%. At the middle-income level, employment is still down 2.6%.

Lawmakers are considering how this translates into what they’re able to spend.

General fund revenues, which come from income and sales taxes, continue to be on the upswing. General fund revenue is projected to grow by 4.6%. That means $791.4 million more in the current fiscal year than what was projected in September, $528.4 million more for the next fiscal year and $582.6 million more for FY 2023-24.

For the next fiscal year, there will be $3.2 billion in one-time money available, which doesn’t take into account caseload increases, inflation or other budget pressures, the forecast said.

One other issue: a decline in K-12 enrollment.

The forecast showed 2.6% fewer students than were forecast last year, or about 22,596 full-time equivalent students. The state’s total public K-12 enrollment is at 843,264, according to the Colorado Department of Education. Largest declines showed in the southwest mountain region, at a 6.7% decline, and on the Eastern Plains, at a decline of 5.2%.

On the flip side, enrollment gains are showing up in northern Colorado (2.4%) and the Western Slope (1.4%). The growth is most obvious in kindergarten enrollment, which is up by 6.2%. The forecast said that enrollment will remain unchanged in the next two school years.

The forecast put the changes on lower birth rates, housing affordability and slowing “net in-migration.”

Economists with OSPB made their presentation virtually, due to a potential COVID exposure in the office, according to Director Lauren Larson.

Their forecast was “roughly similar” to the Legislative Council forecasts, Larson said.

OSPB economist Bryan Cooke told the JBC that supply chain disruptions are taking longer to resolve, which is limiting economic growth. For the region that includes Denver, wait times for products is among the highest in the nation, according to the OSPB forecast.

The good news is consumer income and consumption, he said. Consumer spending is on the rise, particularly in durable goods, and that’s now above pre-pandemic levels.

The OSPB forecast, however, had much grimmer news when it came to U.S. inflation. It estimated the inflation rate at at 6.8%, the highest it’s been in 39 years. Fortunately, it’s been lower for the Denver metro are, at 4.5%, Cooke pointed out. For the next fiscal year, the estimate is 3.3%.

As to employment, the OSPB forecast said that as of May, the ratio of available job openings to those who are unemployed dropped below 1, meaning there are more job openings than available workers. That’s a problem for businesses trying to hire, the forecast explained.

The OSPB forecast also noted a “quit rate.” The forecast explained that “not only has it been difficult to attract workers, businesses are also struggling to retain existing employees. In September, the rate at which employees are quitting their jobs is historically high for Colorado at 4.3 percent, compared to 2.9 percent before the pandemic.” That’s causing businesses to raise wages, benefits and training in their efforts to hire and retain workers.

General fund revenue is expected to hit $16.3 billion for the next fiscal year, reflecting strong growth in personal income, corporate profits and consumer spending.

Economist Meredith Moon said the economic recovery has been “very robust,” adding that the economic headwinds have not been enough to stall it, she explained.

But a lot of the revenue increases won’t stay with the state. Since those revenues will exceed TABOR revenue caps, they’ll go out the door through TABOR refund mechanisms, she said.

Spending available for the budget will remain unchanged for the next fiscal year, Larson told the JBC.

Individual income taxes have led the way, with some $300 million more than anticipated. That’s due to increased wages, as well as the ability to work from home, Moon said.

Corporate profits have been the highest in history, and that’s driving tax revenue increases, the forecast said. Sales and use taxes marked another area of strong growth, which is projected to grow by 12.3% in the next fiscal year.

The forecast also presented a first look at tax revenues from the 2020 ballot measure Proposition EE, which pays for 10 hours of Pre-K education, covers general spending, backfills some of the K-12 budget losses, and pays for tobacco education programs and other health care needs. The forecast said first year revenues came in at $49 million for the second half of the 2020-21 year. That’s well below fiscal projections presented in the Blue Book, which estimated revenues for the same period at $87 million.

OSPB estimated revenues from the EE taxes at $184.0 million in FY 2021-22, higher than the $176 million projected in the Blue Book.