State Supreme Court warns trial courts against exceeding restitution deadline

The Colorado Supreme Court warned trial judges on Monday to abide by an established, although somewhat unclear state law that requires them to decide the amount of restitution to be awarded to victims within 91 days of a conviction.

In issuing its decision, the court agreed that a Garfield County judge did not follow the law by waiting for more than 11 months to decide a convicted robber should repay $524.19.

“Imperfect as our restitution statute may be, trial courts have to find a way to adhere to it,” Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. wrote in the court’s opinion.

Samour, who is himself a former trial court judge, also explicitly laid out the process for how prosecutors and trial courts should abide by the law. At its core, the procedure requires prosecutors to know by the time a defendant is sentenced whether they will seek restitution and to submit their proposed amount within a 91-day window. At the same time, judges are also bound by the 91-day timeline for ordering restitution.

There may be an extension of either deadline with sufficient justification, but Samour emphasized that the mere request for more time does not justify either party blowing past the 91-day mark.

In the case of Benjamin Weeks, a jury found him guilty of robbing a gas station and convenience store. Garfield County prosecutors asked for $524.19 in restitution following a February 2018 sentencing hearing, largely consisting of money Weeks stole during the robbery.

Under state law, restitution covers losses related to the defendant’s conduct and that can be calculated in monetary terms. The defense objected to the prosecution’s calculation, saying the stolen money should be the only amount to be repaid.

However, District Court Chief Judge James B. Boyd waited until January 2019 to approve the prosecution’s restitution figure. Boyd claimed there was “some tension in the statute” about the 91-day deadline but nonetheless argued that he had good cause for deciding on the restitution issue beyond the window allowed by law.

In March of last year, a three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals acknowledged the problem with the 91-day rule: If prosecutors need all 91 days to determine the amount, how is a judge also supposed to order the restitution within 91 days, especially if the defendant needs an opportunity to respond? By a 2-1 decision, the appellate court determined the question was something for the legislature to address. Ultimately, Boyd did not show that he had good cause to delay his decision for so long, the majority said.

The Supreme Court agreed that prosecutors and judges are both bound by the 91-day deadline. The opinion explained that the legislature intended for trial courts to finalize restitution orders in a timely fashion, and consequently Boyd mistakenly held open the window for determining restitution without sufficient justification.

“As we acknowledged from the get-go, the statute is not a model of clarity. Inartful drafting by the legislature, however, doesn’t give us carte blanche to rewrite a statute,” Samour noted.

The court also decided a companion case from Boulder County, overturning a Court of Appeals decision that approved of a judge waiting 15 months after Jonathan Roddy pleaded guilty to criminal trespass before ordering him to pay $688,535 in restitution.

In that case, Roddy entered his ex-wife’s home, took photos and accessed her personal computer files and legal communications related to their child custody proceedings. Ninety days after Roddy pleaded guilty, the prosecution asked for restitution to cover his ex-wife’s costs in the original domestic relations case, as well as the new legal proceedings stemming from Roddy’s actions.

In contrast to the Weeks case, the parties actively litigated the restitution amount during the 15-month window. The Supreme Court decided the trial court was still obligated to determine the restitution figure within 91 days of Roddy’s plea. However, it returned the case to the Court of Appeals for further analysis on whether the judge had, indeed, found sufficient cause to extend the deadline.

“All it takes is really a phone call,” Adam Mueller, the attorney for Roddy, told the justices at oral argument in explaining that 91 days is a reasonable timeframe to determine costs. “If I called our office manager today and asked, ‘What’s the balance on X case,’ it would take 10 minutes and I would have the balance.”

The court, in a related subject raised on appeal, agreed with the Court of Appeals that the trial judge failed to limit the amount of restitution Roddy owed based solely on the harm he caused through the trespassing crime. Unless Roddy had agreed otherwise, he was not responsible for any payments related to the stalking and computer crime offenses that prosecutors originally charged him with prior to his plea.

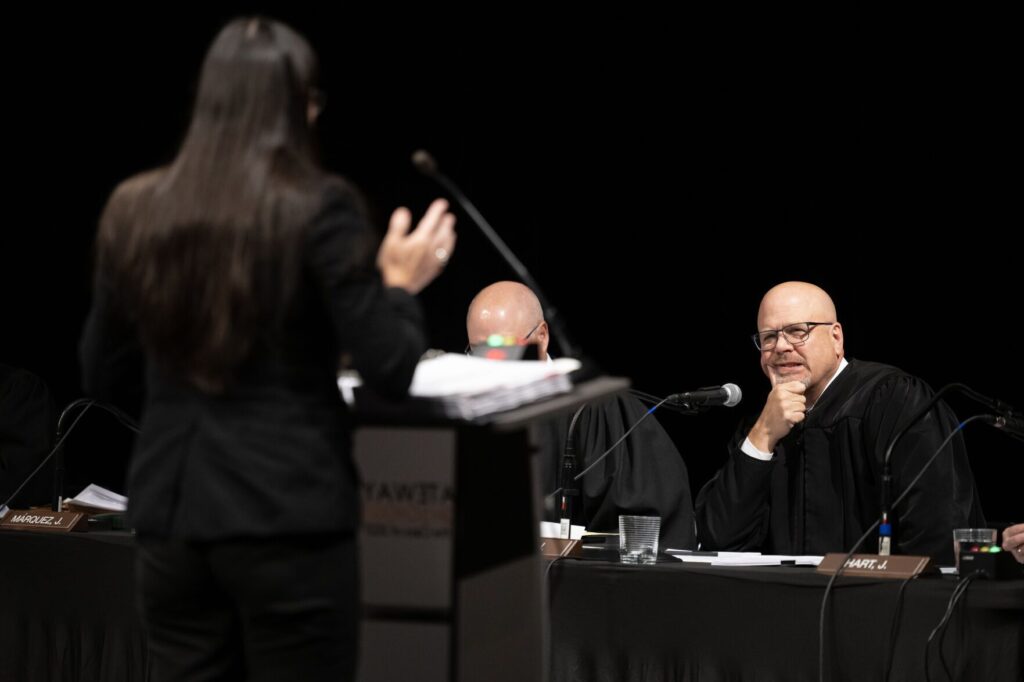

In addition to clarifying the 91-day deadline, the Supreme Court also agreed to examine whether restitution orders still apply after a defendant dies during his appeal. The longstanding practice in those rare scenarios has been to vacate the convictions and leave the deceased as if he were never charged. The justices heard oral arguments on Monday in a separate case about what should happen to restitution still owed to the defendant’s victims in those circumstances.

The cases are People v. Weeks and People v. Roddy. Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter did not participate in the decisions for either. She was the trial court judge in Boulder County who issued the restitution order for Roddy.