RIVER TOWNS | Estes Park and the Big Thompson are bound by the flow of history

Dennis Johnson squeezed the fob to lock the doors of his gray Ford Escape with Nebraska plates inside the four-story parking garage.

A literal stone’s throw away, the Big Thompson River hissed and babbled as it has done for centuries in the spot that came to be known as Estes Park, home to a premier national park, Hollywood fame and the aspirations of enjoyment for generations.

Anachronisms roam the terrain like the elk who wander into town to take a sip and wow the visitors.

The town is perpetually fit for a postcard.

“Everything seems better on vacation, and we like to come to Estes Park,” said Johnson, a 38-year-old insurance man from Grand Isle, as he walked briskly to catch up with his wife and two young daughters waiting on the wooden bridge into town. “I loved it as a kid, and my kids love it now. Right now they love ice cream.”

Estes Park has a relationship with its rivers, creeks and lakes that few, if any, other places in Colorado have. The water problems here are not scarcity or pollution – when you’re this close to the headwaters, all you can blame is Heaven – but too much of a good thing. The destruction from floods have led to reconstruction, and things change despite the attempt to maintain the Estes Park families have treasured for generations.

Kids grow up in this town of 6,300 at 7,500 feet above sea level creating adventure out of majesty. There’s no mystery why millions of tourists visit each summer.

“Well, I guess normal is wherever you live, right?” said Mayor Wendy Koenig, a two-time Olympian who grew up in Estes Park and tries today to calm the turbulent waters of small-town politics against a tide of commerce and growth.

Headwaters head to town

The river is borne from a lush, green valley called Moraine Park about five miles as an eagle flies southwest of town.

The headwaters of the Big Thompson River in Rocky Mountain National Park arrive as rivulets of melting snow from the Continental Divide that collects on the stony floor of Forest Canyon, called Colorado’s “grandaddy of canyons,” by Outside magazine.

“The Big Thompson and its tributaries flow through some of the most popular areas of the park,” said Koren Nydick, the chief of resource stewardship at Rocky Mountain National Park, explaining how everything is connected around here. “People hike to see mountain lakes and waterfalls in its headwaters, campers filter its water for drinking and cooking, and anglers fish along its various elevations.

“Wildlife depends on its moisture and vegetation that grows along its banks. Aquatic insects emerge from its waters and feed a whole host of spiders and terrestrial insects, amphibians, small mammals, birds and bats. In some places in the park it is a prominent feature and in others it humbly flows behind the scenes.”

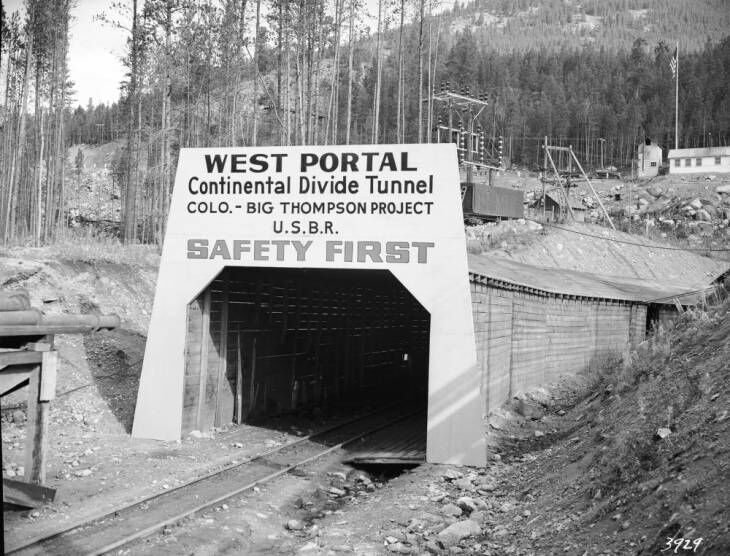

Estes Park, however, is the linchpin of the Big Thompson Project, which pumps 71 billion gallons of West Slope water to the Front Range each year by way of the 10-foot-diameter Alva B. Adams Tunnel. At Lake Estes, it flows through a hydroelectric power plant, conceived and first built by Freelan O. Stanley, the auto-making pioneer who built the Stanley Hotel.

After performing multiple duties in Estes Park, the river flows east to quench the collective thirst of 1 million northern Front Range residents and 15,000 acres of farmland on the Eastern Plains.

“We think it goes through at least three or four uses before it gets to Nebraska,” said Jeff Stahla of the Northern Water Conservancy District, the eight-county utility that oversees the Big Thompson Project.

The vibe of transience makes it somewhat fitting that the river is named for an explorer who never came here flowing into a town named for a family who only briefly stayed there.

The people come

Estes Park has always been a great respite for those coming or going from somewhere else, starting with ancient peoples who hunted mastodons and 8-foot-tall bison antiquus in the valley more than 11,000 years ago.

The Utes and Arapaho followed the fish and game, as well, driving elk and deer from high cliffs to a feast they ate below. They gobbled abundant fish and drank pure, chilled mountain water.

Nearly 100 years ago, three “old warriors” were brought back to where they were children, as reported in the local newspaper. The Arapahoe called Estes Park The Circle, as the place where battles were planned and tribal members danced in inside festival rings.

“Sixty to seventy years ago, the Arapaho Indians were as charmed with Estes Park as the white race today,” the Trail Gazette reported. on Jan. 27, 1922. “It was then a wonder spot, as it is now.”

In good years today, 4.5 million visitors gobble up saltwater taffy from an 86-year-old store or chow down at the original Smokin’ Dave’s BBQ. That works to about 714 visitors for each local, thanks mostly to the river town’s role as the gateway to the country’s second-most visited national park, and the river’s lure for world-class trout anglers, kayakers and rock climbers.

“What we see today with the explosion of population on the Front Range is that same desire to come up here in the summer to one of the most beautiful places in Colorado,” said Jim Pickering, the town’s historian laureate since 2006. “That hasn’t changed, no matter what else has.”

He has written 30 books about the region, and he was busy in June getting a new one about the park ready for his publisher. Pickering also is the immediate past president of the Rocky Mountain Conservancy, chairman of the Estes Park Economic Development Corp until 2019 and former president of the University of Houston.

The commonly told story is that the Big Thompson River is named for explorer and mapmaker David Thompson. Pickering isn’t so sure about that. First, Thompson never got closer to Colorado than Montana. The story has it that the river was named by Simon Fraser, Thompson’s partner in the North West Company who managed British fur-trading posts in the Rockies.

Thompson named the Fraser River in Canada for his friend, and the historical assumption is that Fraser returned the compliment in Colorado. (It’s not clear whether Fraser visited Colorado. The town of Fraser in neighboring Grand County was named for a local sawmill owner, Reuben Frazier. An early local postmaster was a sloppy speller and the spelling stuck.)

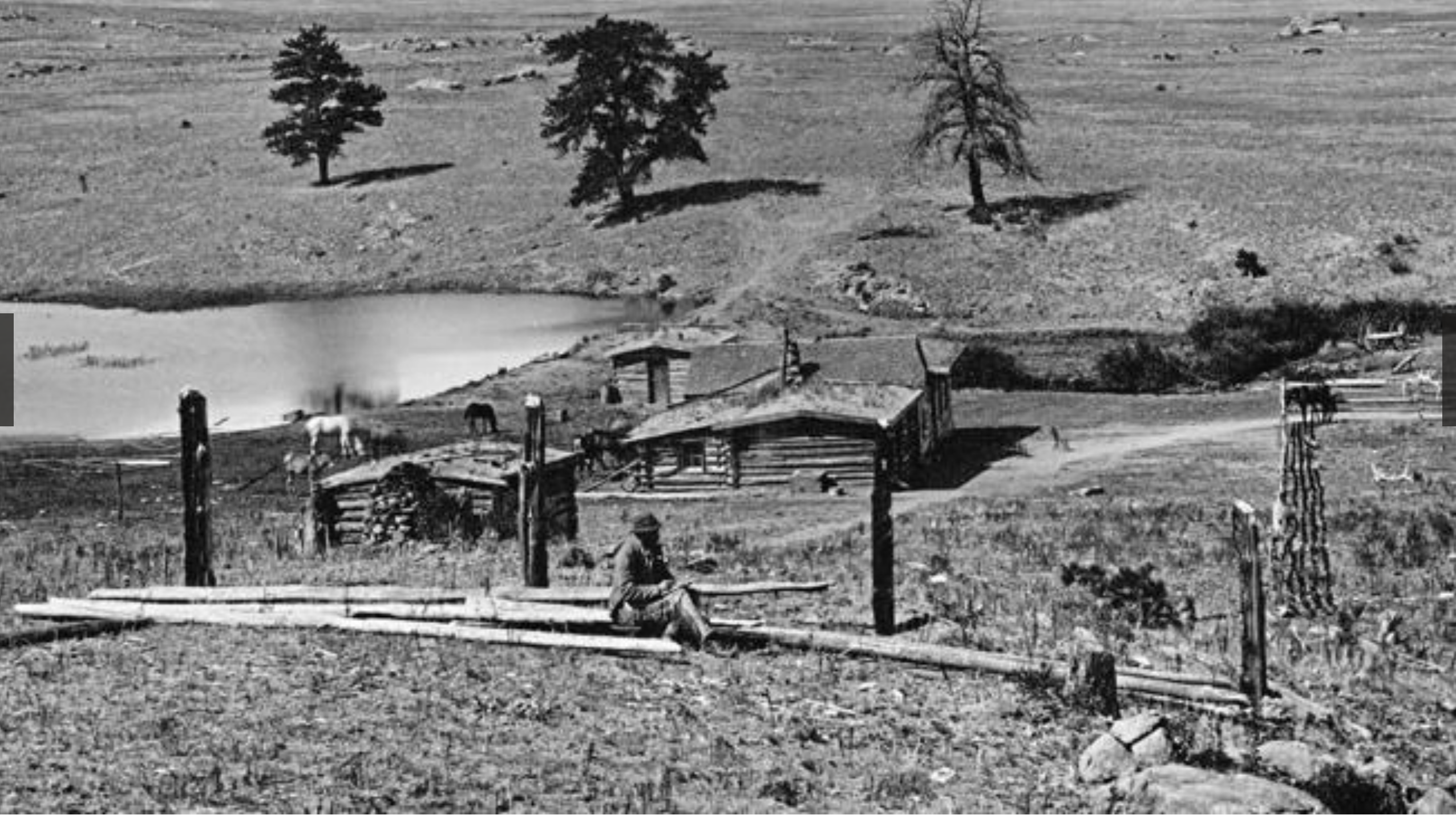

The town’s name came from Kentucky. Joel and Patsy Estes had been to California to look for gold, made some money and liked what they saw passing through Colorado, so they came back in 1859.

Their son, Milton, would write decades later about seeing the Big Thompson’s headwaters for the first time:

“We stood on the mountain looking down at the head waters of Little Thompson Creek, where the Park spread out before us. No words can describe our surprise, wonder and joy at beholding such an unexpected sight. It looked like a low valley with a silver streak or thread winding its way through the tall grass, down through the valley and disappearing around a hill among the pine trees. This silver thread was Big Thompson Creek. It was a grand sight and a great surprise. We did not know what we had found.”

The family built two cabins at the confluence of the river and Fish Creek, where the Lake Estes causeway is today, likely with little concern about a floodplain.

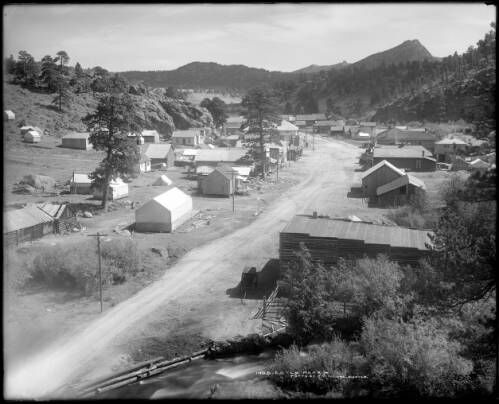

The town sprouted like cottonwoods along the river, and Estes Park has reaped the risks and rewards of its location ever since.

Floods of time

The water has made and remade the valley, however.

A twist of fate and meteorology spared the town from devastation in the Big Thompson River flood in July 1976, the town still drunk with the spirit of the Bicentennial in the Centennial State.

On July 15, 1982, however, the town’s good fortune was reversed, when the remote Lawn Lake Dam, nine miles up the mountain, gave way on an otherwise normal Tuesday morning.

A garbage man saw it first and alerted the town.

“A lake, a dam – something’s flooding!” Stephen Gillette told park dispatchers on an emergency phone that luckily worked.

At 8:45 a.m. a churning mass of water and mud driving ponderosa pine arrived like battering rams down Elkhorn Avenue, the town’s main street, damaging or destroying 177 businesses. Three unsuspecting campers in the flood’s path were swept away, but the townspeople were spared.

“It turned Elkhorn Avenue, the main street in Estes Park, into the river,” the water company’s Stahla said. “They had to rebuild, and when they rebuilt, they were very intentional about creating a river space as part of the marketability of downtown and did some flood control. I think that it has become a fabulous place.

“I mean, it’s not just a love of the river around here. It’s love and respect but a little bit of fear and awe, too.”

On Sept. 11 and Sept. 12, 2013, a rich, subtropical airmass parked over Larimer and Boulder counties and rained 18 inches in 30 hours. The historic meteorlogical anomaly left parts of downtown under 3 feet of water, while economically draining Estes Park of its vital fall tourist season.

All along its route, the raging Big Thompson gobbled up sections of U.S. 34 along the river, costing $300 million to restore. The storm also damaged more than 2,000 homes and claimed nine lives across the region.

River town rolls on

Politically, bad blood can run deeper than the river when the issue is the future.

The mayor before Koenig, Todd Jirsa, survived two recall attempts in one term, then filed a now-dismissed lawsuit against the town he’d just been running over the omission of a constitutional clause in a 2014 agreement related to the Downtown Estes Loop.

The bypass, like the $10 million parking garage by the river, is another step into the future that some here oppose, though Elkhorn Avenue clogs with vehicles and pedestrians each day all summer.

If growth is a swift current, some will get ahead to the dismay of those who came here for a slower flow.

The mayor pro tem in 2019, Cody Walker, was recalled over of his plan to build a gravity-powered “mountain coaster” on former horse-riding trails on the Sombrero Ranch north of Lake Estes. The attraction opened this year, after a zoning dustup with neighbors was settled by the state Supreme Court last year.

It doesn’t take a coaster, however, to get a ruckus going. Almost anything will do, locals will confess with a laugh. In 2005, for instance, David Habecker was recalled as a town trustee after 12 years, because he refused to stand for the Pledge of Allegiance before council meetings; he objected to the clause “under God.” The vote to remove him was 903-605.

Retired international virologist John Meissner, another local historian who doubles as the town rabble rouser, is sometimes the only attendee at public meetings.

Meissner’s family, like the Johnsons, came from Nebraska. They started as tourists in the 1920s and built a vacation cabin without water or electricity in the ’40s.

“They weren’t anybody special, but they were just like so many people: this was their vacation,” he said. “My grandpa would walk to work during World War II to save up enough gas coupons to be able to bring the family up to Estes Park, so that was a big sacrifice. It was a big deal to us.

“This was our summer vacation. My folks would bring us two kids up. I have an older sister. We’d get our school clothes up here. We got to ride the go-karts, play the miniature golf course and play in the water. It was really sad when we left, because that meant the end of summer.”

Enos Mills, a Kansas transplant who would be hailed the father of Rocky Mountain National Park, hitchhiked to Estes Park when he was 15 in 1885. When he was 19, he was inspired by a chance meeting with the conservationist John Muir, who at the time was campaigning to preserve Yosemite National Park.

“The sun shines not on us but in us,” Muir wrote in 1870, the year Mills was born. “The rivers flow not past, but through us.”

In Jan. 26, 1915, two years before the town was incorporated, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Rocky Mountain National Park Act.

The past, present and future merge into one in Estes Park, and the Big Thompson runs through it all.

LEARN MORE

“The Memoirs of Estes Park” by Milton Estes

“Earl Dunraven and the Estes Park Land Grab”

“The First Recorded Ascent of Long’s Peak”

“Nine Colorful Characters Who Made History in Estes Park”

WATCH: “The Living Dream – Abner Sprague”