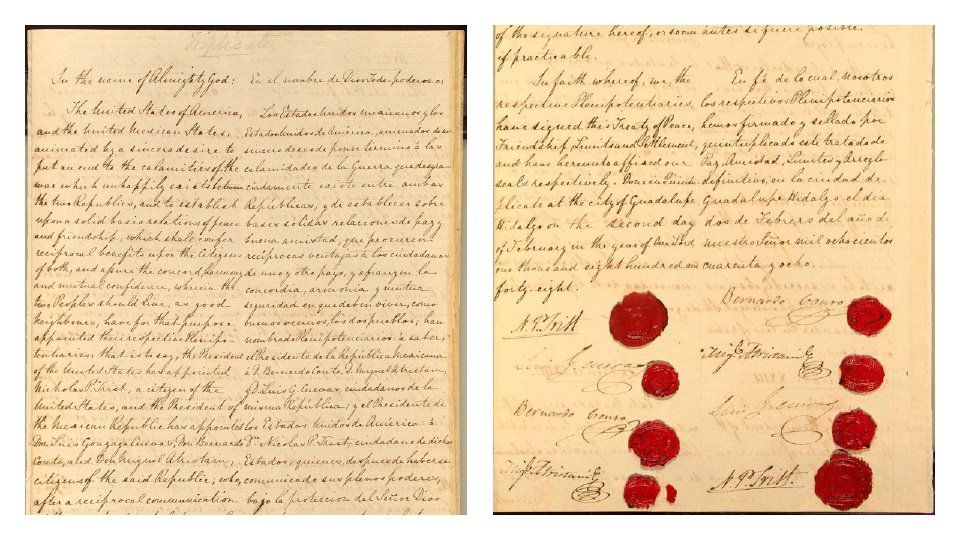

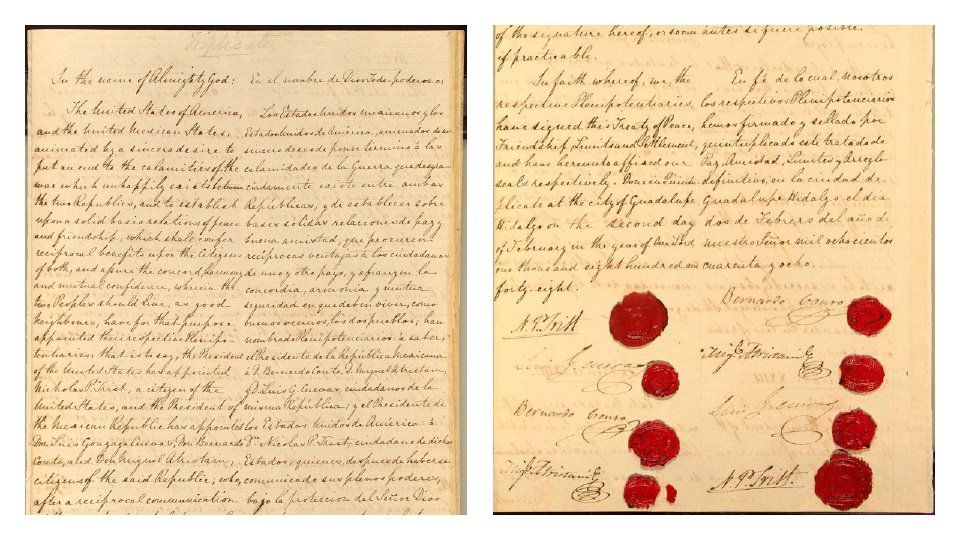

Pueblo museum displaying original treaty ending Mexican-American War

COLORADO SPRINGS – The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo represents both a painful and important part of history.

The document, signed on Feb. 2, 1848, effectively ended the Mexican-American War. It also forced Mexico to accept the annexation of Texas and concede about half of its Mexican territory, including parts of what later became New Mexico, Arizona, California, Utah, Nevada, Wyoming and Colorado.

This history, undoubtedly, reshaped America.

And now, Coloradans have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see three pages from the original treaty through an exhibit called Borderlands of Southern Colorado at El Pueblo History Museum in Pueblo.

The document will be on display until July 4, when it returns to the National Archives Museum in Washington, D.C.

“The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo significantly redefined the geographic and cultural borders of what we know today as Colorado,” Gov. John Hickenlooper said in a statement. “This exhibit highlights an important part of our state’s history that is unknown to many, and honors the ancestral families who made Colorado what it is today.”

It took about a year to complete the exhibit, which will stay permanent after the treaty is returned, said museum director Dawn DiPrince. The project was approved by History Colorado, the state’s historical society.

Organizers got input from borderland scholars and the Pueblo community.

The exhibit focuses on southern Colorado’s geopolitical border history – along with the cultures, ethnicities, landscapes and people that helped make the area what it is today. Visitors can view an interactive map breaking down the shifting zones before and after the treaty was signed, the original Colorado Constitution printed in Spanish and German, an American flag that was made after Colorado became a state and a 1940s kitchen that showcases ethnic food traditions, including Pueblo chile.

But the centerpiece is the treaty.

DiPrince said the museum couldn’t get the first page because of its fragility, but it received pages that declare the border of the United States the Rio Grande and grant Mexican citizens the decision to move to the U.S. or Mexico. The third page shows signatures, including one belonging to Nicholas Trist, the American who negotiated an end to the war – which lasted nearly two years and resulted in thousands of deaths on both sides.

Throughout the planning stages, DiPrince said she and her team kept in mind the impact the treaty made on lives. Their world shifted – some for the better, some for the worse.

Part of the exhibit features a video of local residents telling stories about how their ancestors’ lives changed after the treaty was signed.

“In some ways, the treaty represents loss,” DiPrince said. “There are a number of people from southern Colorado who have been here for centuries, and so, they lived in southern Colorado when it wasn’t part of the U.S. This treaty changed all of that. It changed fortunes. One man told us about his ancestor who went from a landowner to a farm worker with the signing of the treaty. It was a loss of wealth, a loss of land ownership.

“And so, we’re just trying to be very respectful of all the ways in which people may feel about having the treaty here.”