Q&A with Scott Wasserman: ‘The best politics are centered around policy debates, not culture wars’

The Bell Policy Center is by many accounts the brain trust of Colorado’s center-left. Meet the brain-truster in chief, Scott Wasserman. Going on two years now as the think tank’s president, Wasserman helms an operation that provides a knowledge base and idea incubator for many of the state’s leading Democratic policy makers.

But Wasserman doesn’t run his policy shop as an academic exercise in generating wouldn’t-it-be-nice ideas; he’s all about gaining real-world traction for Bell’s policy prescriptions. After all, he hails from the same political trenches as the folks he now seeks to inform and inspire – having served in top posts under Democratic Gov. John Hickenlooper and Lt. Gov. Donna Lynne as well as in the state’s labor movement. He spent time running a Democratic 527 committee, too. He knows the grit of politics.

It’s just that he believes, ultimately, policy is what it’s all about, and he wants to put policy to work. As he observes in today’s Q&A, “If it’s not relevant to the political conversation, why do it?” He’s first, last and always a policy maven. Wasserman talks about that as well the evolving role of organized labor in Colorado; the state’s fiscal dilemma; the crushing weight of student debt, and much more. And there’s also his quest for a good bakery.

Colorado Politics: The Bell debuted the better part of two decades ago, when the state’s political alignment was in some ways quite different from the current one in Colorado. Since then, the left and particularly the populist-left movement for economic justice have become ascendant – especially in the last couple of years with the advent of the Trump administration and, coincidentally, your own arrival at The Bell. How have the Bell’s advocacy and overall mission evolved with that changing political dynamic?

Scott Wasserman: The Bell Policy Center was founded the same year I came to Colorado in 2000. I actually remember calling the Bell’s first president when I was looking for job leads. It was around that time the political realignment you mention was taking hold. My first job in Colorado was slinging press releases for the state house Democrats when we were reeling from our first big post-TABOR recession. What made matters so much worse was a new anti-tax, libertarian strain of Republicans who had taken over Colorado in the 1990s and they had just permanently reduced income taxes. When the recession hit, the state had no choice but to cut vital services. The Bell cut its teeth on the fight for Referendum C, which was the response to that crisis. Even with that important vote, we never really recovered from the cliff we went off of in the early 2000s. If you think about it, since that point, we’ve declined in nearly every indicator of economic mobility – in child care, in higher education, in k-12, in human services. Today, any collaborative effort to make people’s lives better is met with a scarcity mentality that makes no sense at all for a state as prosperous as ours.

And it turns out that’s exactly how a very well-funded political operation backed by two brothers out of Kansas wants to keep it. The Koch Brothers are pulling our political debate further and further to the right. That’s why we’re seeing this political rhetoric in our State Capitol that frames the needs of citizens as outside interests and insists on digging our fiscal hole even deeper than it already is.

Today, I think the challenges we face are so much more immense than 18 years ago because income inequality is starting to lock in. Even as elected offices may have switched hands back and forth all these years, the anti-tax ideology has been able to to achieve its goal. We are now a state of cruel paradoxes: the number one economy, but in the back of the pack in every area that is key to our future success.

The difference between the Bell in 2000 and the Bell in 2018 is a lot more urgency and a refreshed analysis that takes into account not just shrinking public resources, but also income inequality, demographic change, and the rise of new technologies that are changing the way we work and learn.

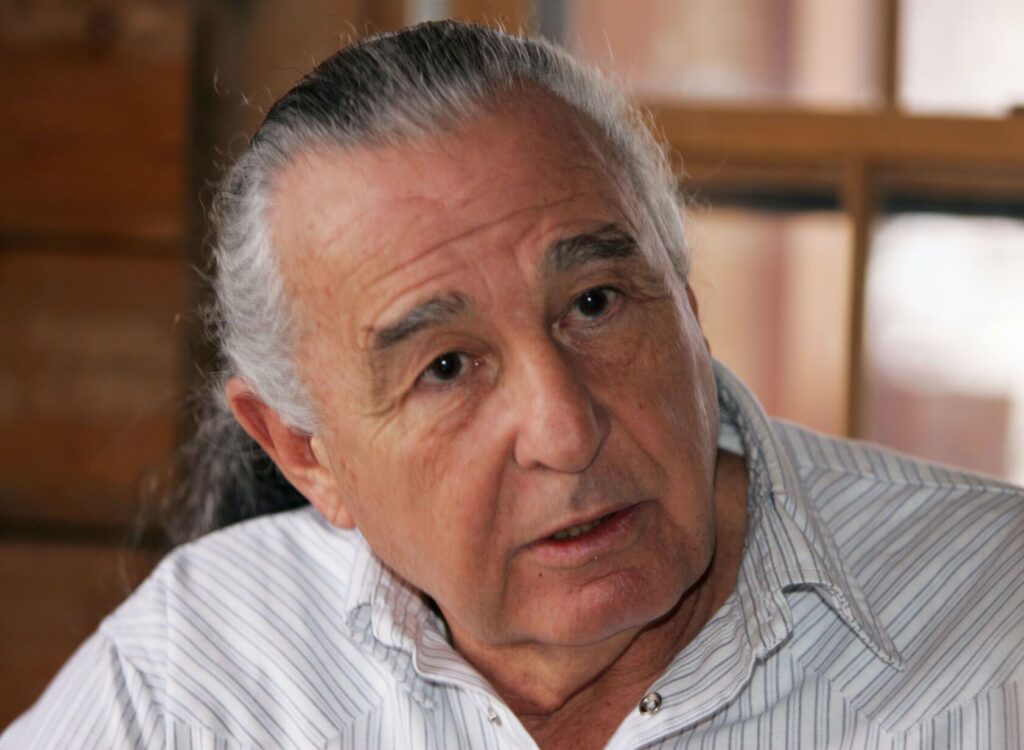

Scott Wasserman

CP: The Bell is a prominent voice regarding the public’s struggle with debt, and you have called for reforms – to payday lending, student loans and more – to protect borrowers. Your organization has been highly critical of the Trump administration’s move to limit state regulation of student-loan servicers, whom you accuse of predatory lending. Lending practices aside, though, how do we tackle the underlying issue that drives student debt: the soaring cost of a higher education? And does the relatively easy access to student loans ironically encourage colleges and universities to hike tuition even further?

Wasserman: It turns out the response to receding public investment is a steep rise in crippling debt.

You want a taste of what we call predatory economy? Put yourself in the shoes of a Coloradan who is paying off student debt, but who doesn’t even have a degree or career to show for that monthly payment.

Over the past 20 years, our higher education system has incentivized putting butts in seats rather than investing in student success. That creates the perfect conditions for the growth of for-profit colleges that have much lower completion rates and much higher debt levels.

Fifty years ago, public college was virtually free in this country. This was a traditional American support that was key to our economic success. My father was the son of a working poor tailor, and our family was able ascend into the middle class in just one generational leap because of it. In his time, that story was commonplace. Today, that kind of leap is the exception, not the rule.

Here in Colorado, with the nation’s best economy, we are now 46th in spending per student in higher education. We’re starving ourselves for no good reason and if we don’t fix the situation, it’s going to really damage our future competitiveness. We know high student debt levels are a huge drag on the economy. A recent study that showed by forgiving all of our nation’s $1.4 trillion in student debt, we would actually add $100 billion per year to our GDP. That gives you a sense of the scale of economic drag we’re talking about here.

But we can turn all of this around. When I worked for Joe Garcia, who was also the director of (the Colorado Department of Higher Education), we were focused on two prime tasks: close attainment gaps so every student who enters the system succeeds, and reduce the dependence on debt for as many Colorado families as possible.

The big task ahead is actually re-engineering our entire postsecondary system so it’s flexible and available whenever Coloradans need to retool or change careers throughout their working lives. I think we all know there’s no way that kind of a system can exist with debt as its primary funding source.

CP: Your résumé attests to your experience in the hardball side of political advocacy. You helped run the shop at the governor’s and lieutenant governor’s offices; you oversaw political strategy as well as the ground game for organized labor and for a Democratic 527. Your move to a think tank seems to shift gears and take you onto a more philosophical and theoretical track. Or, is it just the continuation of politics by other means?

Wasserman: I’ve had the opportunity to engage in all kinds of different politics and I really believe the best politics are centered around policy debates, not culture wars or personality preferences.

Moving over to the Bell has given me the opportunity to work with a great team that is entirely focused on going deep on the challenges facing our state and thinking creatively about the best policies that will move us forward. The thing about this work is that it’s a moving target. We inherit the policy choices of the last political generation, and those choices create the circumstances the next generation needs to react to.

But there’s nothing theoretical about this work. If it’s not relevant to the political conversation, why do it? We’re here to be a resource for policymakers, advocates, and activists who want to ensure economic mobility for every person in this state.

CP: As in most of the interior West, organized labor has never played a big role in Colorado’s private-sector economy. Yet, it occupies a prominent place on the state’s political scene because of its firm footing among public-sector employees, particularly teachers. Is that the future of the labor movement in Colorado – and nationwide – as the advocate for government workers?

Wasserman: Colorado has always had lower union rates than the rest of the country, but I was actually surprised recently to see union membership has been on a slight rise here since 2010. That’s driven not only by some gains in the public sector, but also in the low-wage service sectors.

I often say nobody wants a labor union in their backyard, but they sure as hell want one in the neighborhood. Unions are messy because they challenge employers’ power and they force uncomfortable questions, but they are essential to a thriving middle class and an upwardly mobile economy. It’s no coincidence that as union density has gone down in this country, wages for all workers have followed suit. Organized labor faces many challenges, not least of which is a very well-funded effort to chip away at the right to organize. Even without the powerful opposition they face, the rise of the gig economy means unions won’t have cleanly defined groups of employees to organize and fewer large employers to negotiate with.

But you know what? That’s not just the labor movement’s problem. All of us need to think about the dramatic changes unfolding in our economy. How do we get wages up? How do we ensure everyone has a secure retirement future? What protections do employees have as they retool for the jobs of the future? In the 20th century, the answers to the questions were largely shaped by the labor movement. In the 21st century, the labor movement will either have to innovate its model to regain its footing, or we as a country will have to come up with new mechanisms to rebalance the system.

Colorado is getting older and we’re getting more diverse. The political movements that acknowledge those trends and solve the challenges they bring will be rewarded by the voters. We have entire communities we need to invest in and we have huge inequities to close.

CP: It is easy to see Colorado as trending blue in the current political climate; the scales certainly seem to be tipping that way. Yet, perennially purple Colorado has tilted back and forth before. Do you think this time the shift to the left promises to be longer-lasting and, if so, what characteristics of the electorate suggest that?

Wasserman: There are a lot of folks in this town who are far more qualified to give you that kind of electoral analysis. In my role at the Bell, I’ve been reflecting on our state’s demographics and two things smack you in the face: Colorado is getting older and we’re getting more diverse. The political movements that acknowledge those trends and solve the challenges they bring will be rewarded by the voters. We have entire communities we need to invest in and we have huge inequities to close.

Right now, I see a Republican Party that’s been captured by a hard-line ideology that refuses to accept these realities, and a Democratic Party that is mired in a debate about who it represents and how it should present itself to the voters. I don’t think the ascendance of either political party is certain.

What we really need is trans-partisan collaboration around the central endeavor of renewing the infrastructure we inherited from the last generation. I don’t know how we get there in the current political environment, but I really do think we’re running out of time. Frankly, it’s hard for me to think past 2021. That’s probably when we hit the TABOR cap again. Unless the education and transportation tax measures that are being talked about for this fall are passed by the voters, we’ll be giving away rebates even as we’re forced to close colleges. Regardless of their party affiliation, whoever captures the Governor’s Office in this next election absolutely must end Colorado’s hunger games.

CP: You are by all indicators a dyed-in-the-wool Democrat, yet Colorado’s No. 1 political affiliation among voters – unaffiliated – must give you pause just as it does Republicans. Is it a cause for worry for the two traditional political parties? What’s your take on the Unity Party?

Wasserman: If you think I’m diehard, you should meet my wife.

For me, our growing number of independents is a sign that our state is not fixing its problems.

When you talk to independent voters, you hear about really practical problems that need solving in this state. They feel economically stuck, they’re worried about growth, and they’re worried about the future. They’re tired of what they see as monied political interests gumming up the works. They’re frustrated and they’re fed up that enough political gravity hasn’t built up around their issue to get it solved.

Rather than see these independent voters as one big homogenous blob, we should look at them as issue-driven voter blocks.

I’m actually of the mind that the two-party system in this country is one of our great downfalls. I spent a lot of of time studying multi-party democracies and there’s something to be said for the importance of the ability to build political coalitions that meet the needs of the moment.

Of course, getting to a multi-party system is nearly impossible and minor third parties only serve to throw elections into unpredictable and often unconstructive directions.

CP: You’re from New Jersey – not that there’s anything wrong with that! What brought you to Colorado and what’s keeping you here?

Wasserman: I came to Colorado right after I graduated from college, looking for some fresh perspective and a break from the clutter of the East Coast. What keeps me here? I can’t imagine raising my kids anywhere else and the food has gotten dramatically better from when I moved here 18 years ago. I actually almost left because I couldn’t find a decent bakery. Still can’t actually. I heard a rumor Joey’s going to open one soon. Can you confirm that?