Colorado’s Medicaid crisis was years in the making | OPINION

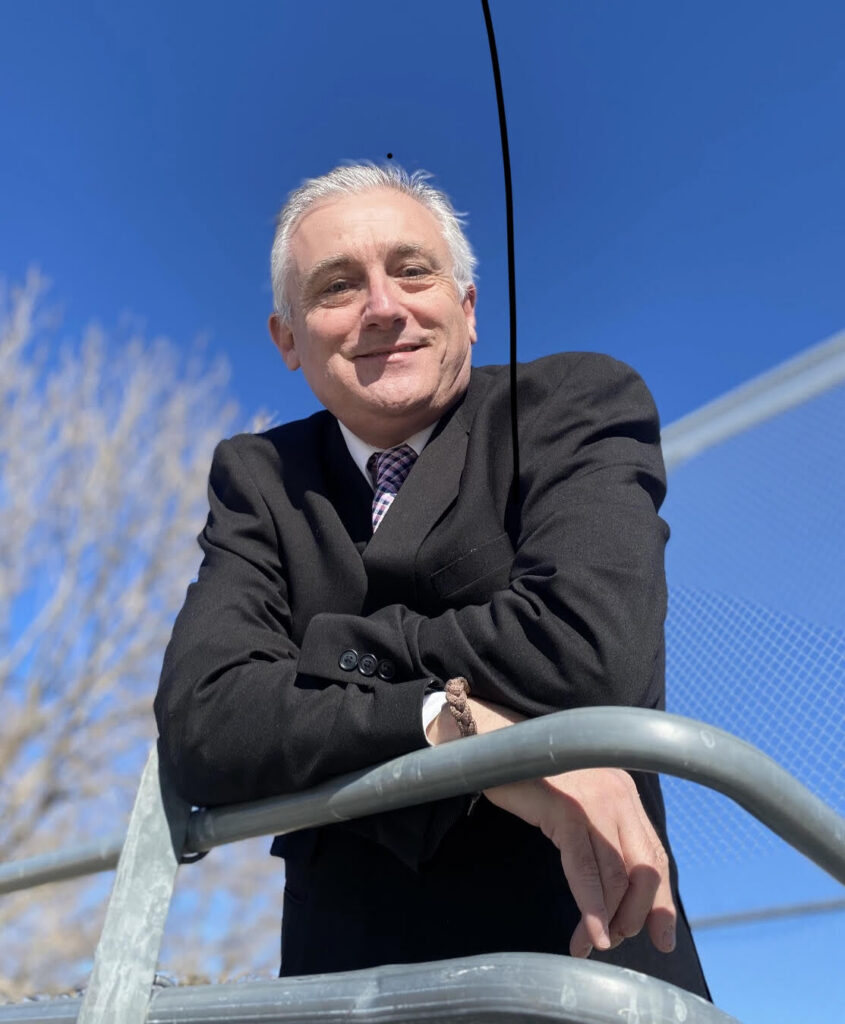

By Greg D’Argonne

As the Joint Budget Committee meets to finalize spending decisions for the coming fiscal year, one truth should guide the conversation: Colorado’s health care budget strain did not appear overnight — and it is not the fault of hospitals, doctors, or any medical provider.

Health care spending itself is at the heart of Colorado’s current financial situation. For several cycles, the state has dealt with expected shortfalls on its budget proposals, as detailed in its own communications and output.

This health care spending growth goes a long way in explaining why the state’s budgetary situation is at it is. The Department of Health Care Policy and Financing (HCPF), which administers Health First Colorado, now commands nearly 37% of the state’s operating budget — more than any other line item, including education.

That spending mushroomed in a very short time, more than doubling in just 10 years. In fiscal year 2025, HCPF spending reached almost $16 billion. A decade ago, it was just under $8 billion.

This outpaced state spending at every other level. During the same period, the rest of the state budget grew by 64%.

This was not a feature of health care becoming more expensive or more expansive, which is the usual explanation for Colorado’s health care spending growth. Between 2015 and 2025, HCPF’s spending growth outpaced the combined growth of Medicaid enrollment and medical inflation. Even after enrollment declined sharply following the expiration of pandemic-era protections, spending continued to climb.

If HCPF’s budget had followed those items, in fact, the state would have saved more than $5 billion. According to my analysis with the Common Sense Institute, where I serve as a health care fellow, if HCPF’s budget had simply tracked caseload, inflation, and public health trends, it could have spent roughly $10.8 billion in fiscal year 2025.

Instead, it spent $16 billion.

That gap is not driven by patient need. It is driven by policy decisions.

Between 2019 and 2025 alone, lawmakers enacted 182 new health care-related bills. Many bills expanded coverage mandates, increased administrative requirements, or added regulatory layers to providers. These policy additions now cost at least $858 million annually in state funds, not counting the additional federal matching dollars they trigger.

Those regulatory barriers and layers of bureaucracy stack up.

The proof for this is in HCPF’s growth relative to Medicaid’s in the last few years. Medicaid enrollment rose by just 7.6% between 2018 and 2024. During that same period, HCPF’s full-time employment increased by 72%, and administrative spending doubled.

This is not an argument against Medicaid. It is, however, a plea for Medicaid to be managed responsibly at the state level.

Hospitals do not drive the state’s budget instability. In fact, many have been operating under growing pressure from HCPF policies.

Consider the Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) program. Over five years, Colorado’s RAC auditors recovered $84 million in alleged overpayments. At the same time, Colorado has been the only state that does not fully reimburse hospitals when underpayments are discovered.

The administrative burden on hospitals remains significant even after reforms.

The Hospital Transformation Program (HTP), a well-intentioned but complex initiative that many providers say duplicates existing federal and accreditation requirements. Hospitals report heavy documentation burdens, shifting performance standards, and limited alignment with other quality initiatives. For rural facilities operating on thin margins, these administrative requirements divert resources away from patient care.

The strain is compounded by Medicaid disenrollment trends, as hospitals eat the costs of the uninsured.

Between 2023 and 2025, about 500,000 Coloradans were removed from Medicaid rolls as pandemic-era eligibility protections expired. Colorado’s disenrollment rate was 48% of redeterminations, far above the national average of 31%.

Many of those individuals became uninsured.

In the first quarter of 2025 alone, Colorado hospitals delivered $140 million in uncompensated care. This is double the level of 2023. Emergency room visits by uninsured patients have surged, particularly in metro Denver.

When Medicaid administration falters, costs do not disappear. They shift to hospitals, privately insured families, and rural communities least able to absorb them.

The Joint Budget Committee has an opportunity for course correction.

Federal Medicaid changes under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act will not take effect until 2027. The immediate challenge facing the General Assembly is state-level spending discipline.

Lawmakers should examine where HCPF has grown past necessity. They should revisit regulatory expansions that add cost without improvement in care. They should ensure audit systems are balanced and collaborative. They should consider whether the Hospital Transformation Program, now up for reauthorization, should be restructured or allowed to sunset.

Containing costs does not mean abandoning care. It means focusing dollars on patients and taking careful steps to ensure they don’t get soaked up by new layers of bureaucracy and administration.

Lawmakers should consider whether to continue expanding bureaucracy, or recalibrate toward sustainability.

Greg D’Argonne is the Common Sense Institute’s health care fellow and former chief financial officer for HCO Continental Division.