Colorado’s lack of snow pack hurting outdoor industry; could spell drought conditions this summer

A snowy weekend forecast in January was a relief to skiers, hydrologists, fire officials and ski resort staff in Colorado as the state continues to see record high temperatures and record low snowfall.

A USDA map showed the average statewide snowpack on Tuesday at 58% of the median. It’s the lowest snowpack year Colorado has seen on average since the late 1970s, a National Weather Service hydrologist told The Denver Gazette.

Since the start of the dry winter, scientists, ski town officials and recreators have grown increasingly concerned about what a low snowpack year could mean for the state.

Ski traffic, fire danger and avalanche risk are still mimicking early season trends as February creeps closer, and only time will tell if Spring will bring the amount of snow the state needs to avoid a summer of high wildfire risk and low water basins.

THE OUTLOOK

Colorado gets most of its annual snowpack between February and April, and National Weather Service forecasters aren’t yet sure how those months will play out.

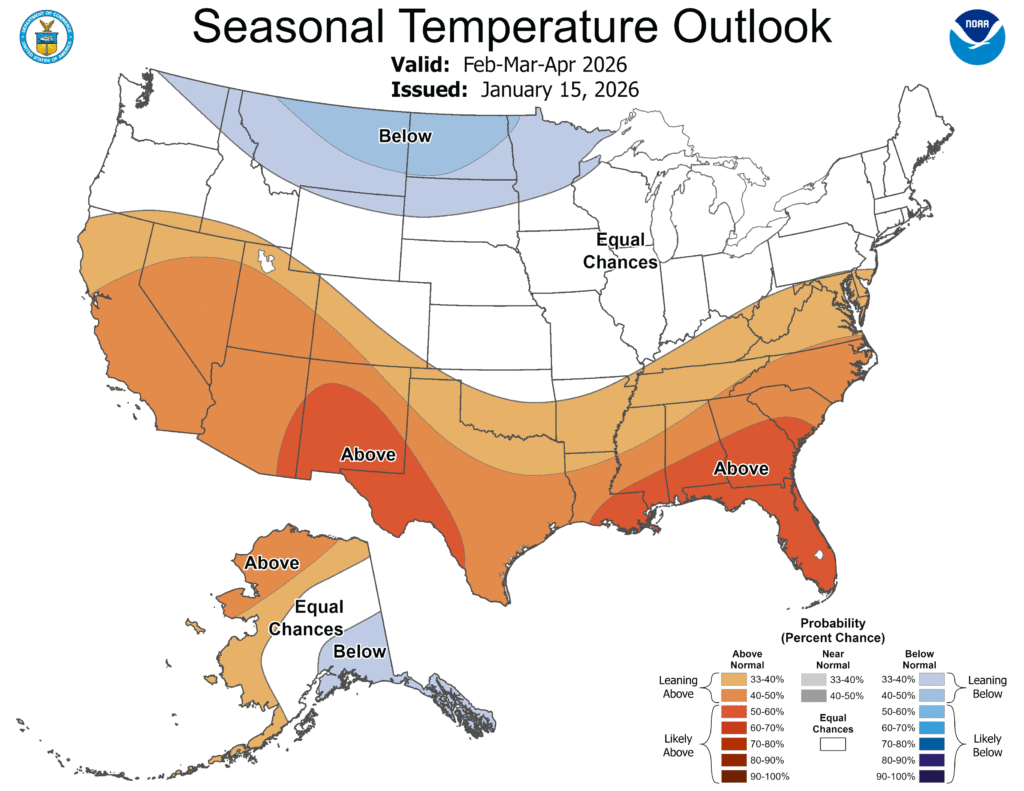

An NWS temperature outlook shows February, March and April in northeast Colorado in the “equal chances” zone of having above or below normal temperatures for the season. The southwest portion of the state is predicted to have above-normal temperatures through the spring.

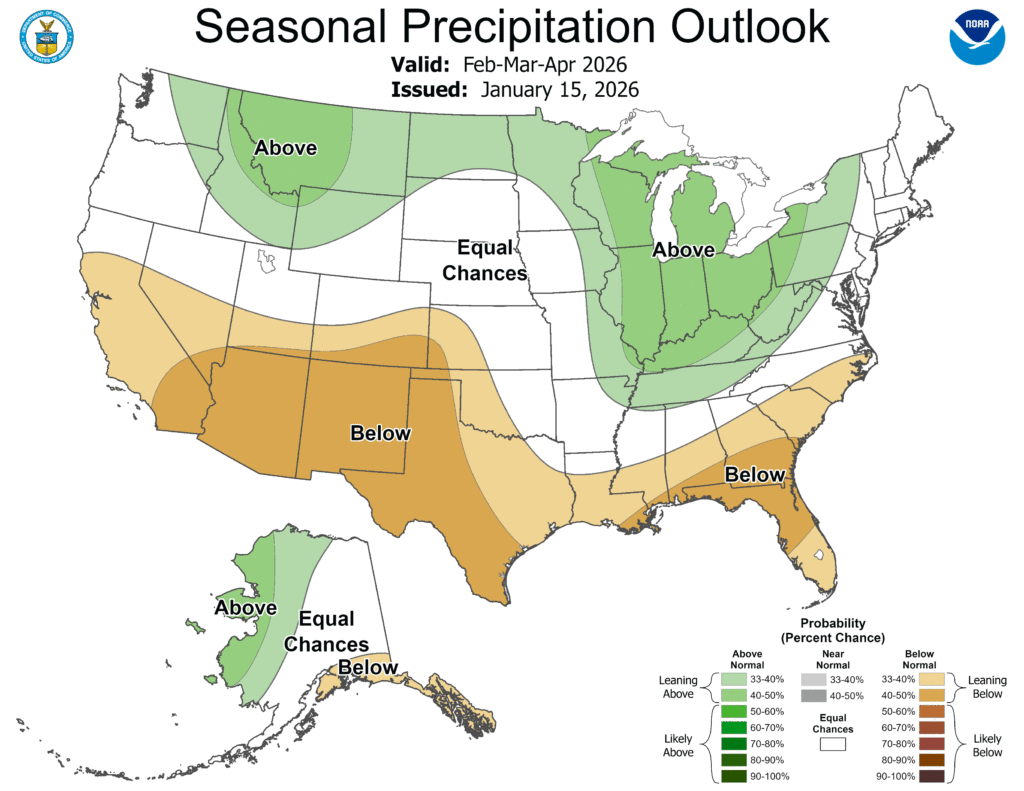

A seasonal precipitation outlook shows northern Colorado in the “equal chances” zones of expecting above or below average precipitation for the season and southern Colorado expecting below average precipitation during the same time frame.

SKIING, OR LACK THEREOF

The low snowfall and warm temperatures are no secret to outdoor recreators, who are making the most of rocky ski slopes and questionable conditions.

Vail Resorts CEO Rob Katz said Vail’s western United States resorts saw snowfall 50% below the historical 30-year average in November and December.

Normally, Keystone and Breckenridge have about 90% of their terrain open by mid- to late-January, spokesperson Sarah Mclear said.

Going by trail open numbers on Jan. 27, Keystone sat at about 71% open and Breckenridge at 46%.

Skier numbers are also down about 20% at Vail’s resorts this year, according to a press release comparing this season year-to-date to last season in the same timeframe.

At Crystal Ski Shop in Boulder, staff have seen repairs “indicative of the winter we’re having,” spokesperson Benjamin Dickson said.

The low-snow conditions giving way to rocks have, unfortunately for customers, been good for Crystal’s repair shop, Dickson said.

“We’re seeing more and more core shot (deep ski damage) repairs,” he said. “It’s not the kind of thing we wish upon any of our customers, but it does mean our tune shop is doing well.”

Crystal has also seen a swell in turnaround times for tunes and repairs, he said, as more people come in with damages and rush to the slopes at the first sign of any snowfall.

At Breckenridge and Keystone, the name of the game this season has been creativity when it comes to ensuring a positive experience for visitors, spokesperson Mclear said.

At Breckenridge, 30 of the mountain’s total 35 lifts and 87 of the mountain’s 188 trails were open as of Jan. 27, according to an On the Snow ski report.

Keystone has all of its lifts open and 99 of 140 trails open on Jan. 27, the report said.

CEO Katz said Vail Resorts experienced one of the worst early-season snowfalls in the West in more than 30 years, which has hurt visitation.

Despite the snowfall challenges, resort officials have faced the season with determination and creativity, Mclear said, finding strategies to improve mountain conditions and bringing other fun activities to the resort to improve the visitor experience.

Colorado mountain resorts have implemented a variety of strategies to get skiers on new snow to pack it down while limiting the number of skiers on the snow to keep it from getting skied out.

For Breckenridge and Keystone, this means opening some terrain as “walk-to” only, and opening limited-time terrain.

In a similar fashion, Arapahoe Basin started a directed skiing program, which involves opening terrain to a group of skiers led by a ski patrol guide, resort sustainability manager Mike Nathan said.

Snowmaking teams have relied on skill and creativity this season more than ever, figuring out the best places and times to make snow to please skiers and get the most out of snowmaking resources, Keystone’s Senior Director of Mountain Operations Kate Schifani said.

Ski resorts only have a certain amount of water to use, and efficient snowmaking is all about time, place and strategy, she said.

Snowmakers at Keystone had a season-long plan for snowmaking and scrapped it on day 10 due to the unusually warm season, Schifani said.

They shifted gears, realizing their strategy for the season needed to prioritize and rely on travel, she said. Most seasons, there’s enough natural snow to access places that need snowmaking via snowmobile. This season, they did “a lot of walking.”

Terrain they opened as a result was different than what they would’ve opened otherwise, she said, and the new strategy was successful and got a lot of praise from skiers.

“We had to figure out how we stayed connected while traveling around the mountain with the snow we had,” she said. “We had to bring the snow with us wherever we went.”

The biggest hit has been to terrain above tree line, where resorts don’t have snowmaking equipment and wind has a bigger impact, Mclear said.

Vail spokesperson John Plack added that the Epic Pass’s commitment model is “central” to Vail resorts navigating variable weather.

“By locking in revenue ahead of the season, we’re able to continue reinvesting in our resorts and elevate the guest experience,” Plack said. “In addition, we offer a geographically diverse portfolio of resorts, giving guests options — so if snow conditions aren’t where we’d like them to be in Colorado at a given moment, our guests still have choices.”

Meanwhile, Ouray Ice Park’s 31st annual Ice Fest is celebrating “Ice(less) Fest,” saying on its website that “uncharacteristically warm temperatures” resulted in ice that isn’t safe to climb.

“The ice is just one part of why we gather, the Ice Park website says, urging visitors not to cancel their trips. “The true spirit of Ice Fest is in the community, the shared passion, and the celebration of our lives in the mountains.”

FEWER, SMALLER AVALANCHES, BUT STILL A RISK

Ethan Greene, the director of the Colorado Avalanche Information Center, has seen a substantial decrease in the number of reported avalanches this year.

Between Oct. 1 and Jan. 27 this season, CAIC received reports of 1,095 avalanches.

In that same time period in the 2024-25 season, there were 2,132 reported avalanches.

Avalanches that have been reported this year are also smaller than what is normal for January, Greene said, adding that avalanche activity is similar currently to how it usually is in November.

Of this season’s 1,095 reported avalanches, 55% or 607 were D1, the smallest size ranking for avalanches.

Last season, during the same time frame, 39% — or 831 of the reported avalanches — were D1.

Most notably, Greene said, the variation in avalanche danger throughout the state is “very unusual.” While it’s common for certain areas to have different avalanche forecasts than other areas at any given time, this season has blown that variability up because of the differences in snowpack across the state.

“The variation is dramatic and the range is unusual between places with virtually no snow to places that are very easy to trigger an avalanche,” he said.

The snow Colorado has seen so far this season has been “very weak,” Greene said, which will translate into high avalanche danger when snow falls on top of it.

As Greene predicted, CAIC warned of risky avalanche conditions across the state in a news release Friday ahead of the weekend storm.

Over the weekend of Jan. 23 to Jan. 27, during which new snow fell over the front range area and in the mountains, 183 avalanches were reported across the state to CAIC.

Like trends in avalanche behavior, trends among backcountry-goers are also mimicking early-season, he said. People flock to backcountry places where wind has blown snow or sun hasn’t melted it, which are also the places where avalanches pose the highest risk.

While many of this year’s reported avalanches have been small, Greene urged people to consider the dangers of small avalanches.

“Even if an avalanche is small, it can wash you into rocks, trees or cliffs,” he said. “Low snow does not necessarily equate to low danger.”

No matter the snow conditions, Greene said the message to backcountry recreators stays the same: take the proper steps to take care of yourself.

“Check the forecast, have the right equipment including a beacon, shovel and probe, make sure your group knows how to use them and make good decisions based on your risk tolerance and the kind of day you want to have,” he said.

WATER

National Weather Service Hydrologist Aldis Strautins isn’t worried about the water impact of a low snowpack year yet, but time is ticking, he said. In order to ease his worries, the state would need multiple big snowstorms this spring.

Colorado has a little more than 70 days left to reach normal snowpack for an adequate water supply this summer, Strautins said.

“We still have time to make some of this snowpack up, but as we get farther along and don’t get enough snow, it will be harder,” he said. “I’m not worried yet, but I’m monitoring.”

Hydrologists will have a better idea of the snowpack’s impact on water come mid-February and early March, he said.

This season has also presented record warm temperatures, with the USDA reporting the average air temperature in October and November as the second warmest on record, dating back to 1895.

Precipitation trends across the state in early January were close to historically normal levels, but the higher temperatures have meant the precipitation falls as rain rather than snow, a news release from the USDA said.

USDA streamflow forecasts for the 2026 runoff season and reservoir storage forecasts are below normal for most of the state.

HEIGHTENED FIRE RISK

Rocco Snart, the fire planning branch chief for Colorado’s Division of Fire Prevention and Control, is also biding time before the worry sets in for an extra risky fire season, he said.

“If this weather exists (in the Spring) and doesn’t transition into something more favorable, it could be extremely problematic for us,” Snart said. “Depending on what March and April look like, that’s the key piece for us that will impact the summer season.”

Snart, who has been in fire service since 1985 and wildland fire management since 2002, pointed to the snowpack in January 2000, which was similar to what the state is seeing this year.

“Low snowpack throughout the state translated into a very significant fire season in Colorado,” Snart said.

The lack of winter weather in the mountains also provides more habitable conditions for mountain pine beetles, which have devastated millions of acres of forest across the state, increasing wildfire risk and threatening forest health, Snart added.

“These are prime conditions for (mountain pine beetles),” he said. “Winter can slow them down, but with the warmer temperatures, those beetles will be in a position where they can extend that epidemic a little bit.”

There are a lot of variables that will determine how the fire season plays out, he said, and the public can help by taking care when they’re outdoors and doing things that could cause unintended fire situations.

While fire officials in the DFPC don’t plan to make any significant staffing changes to address increased risk, they will plan to be able to move their resources around the state as necessary, Snart said.