Denver Public Schools enrollment losses outpace school closures

Enrollment losses in Denver now outpace what school closures alone can address.

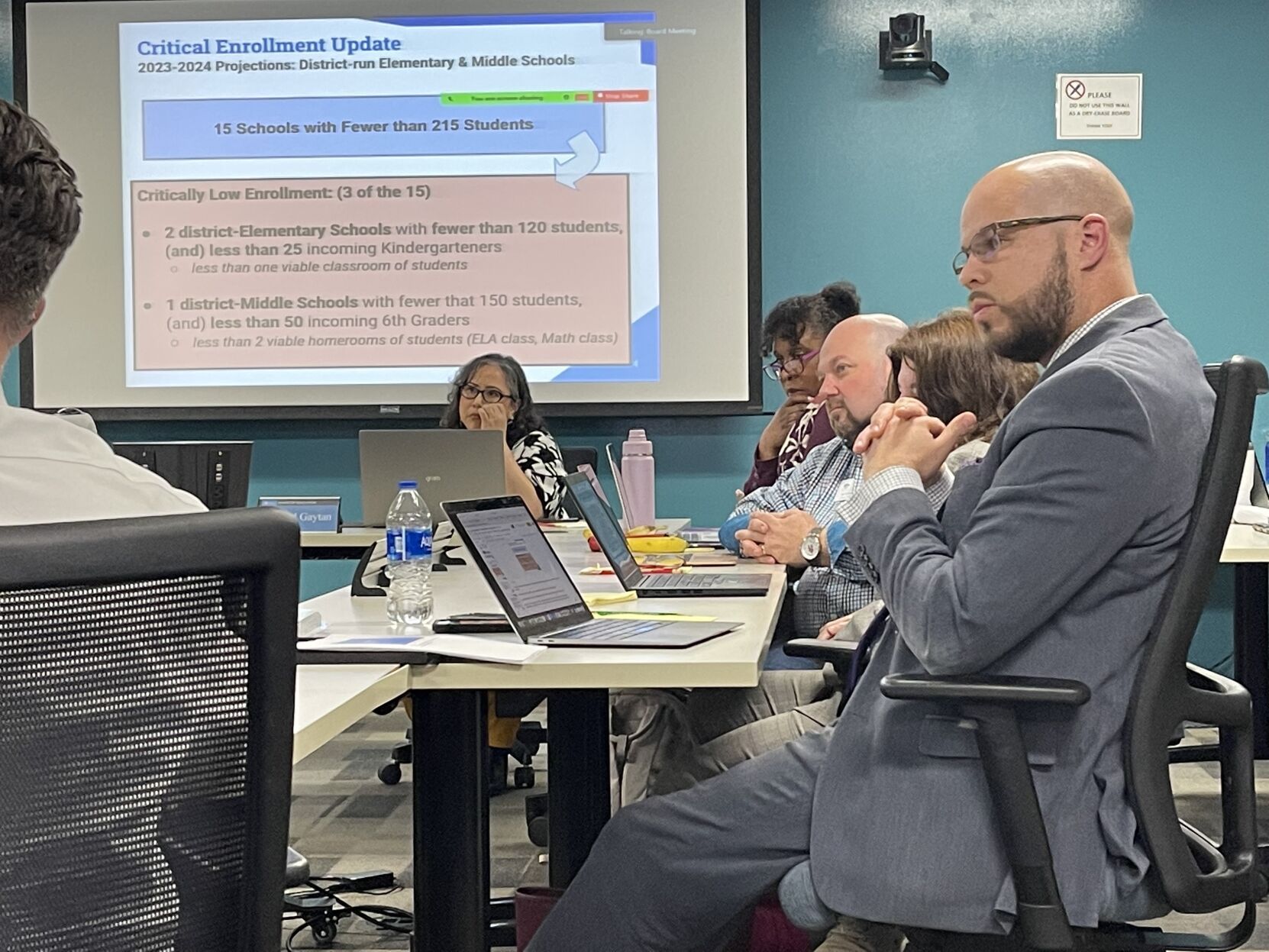

Denver Public Schools (DPS) Superintendent Alex Marrero is expected to present an update on the district’s enrollment to the board at its meeting this Thursday.

During an October count, the district reported an enrollment decline of roughly 1,200 students and about $18 million in lost annual revenue, said Bill Good, a district spokesperson.

Because of a practice known as “smoothing” — which averages pupil counts over three years, rather than a single year — the immediate impact has been reduced to about $9 million.

District officials anticipate those losses will grow substantially once smoothing phases out, reaching roughly $70 million annually over the next four years.

To put the district’s enrollment losses into perspective, closing seven schools and restructuring three others last year saved DPS about $29.9 million.

It costs about $4.7 million, on average, to operate a school, according to the district. Depending on enrollment, costs can range from roughly $2 million to $19 million.

Taken together, the figures underscored why district leaders are now pointing to boundary and enrollment changes as the next lever.

In materials the district briefly posted online and later removed, officials distinguished between school closures — governed by a separate board policy that is currently paused — and Executive Limitation 19 (EL-19), which focuses on adjusting enrollment boundaries and zones to reflect demographic and housing trends.

The materials also described a multi-year process for implementing EL-19, beginning with internal planning in 2026 and culminating in boundary or zone changes reflected in school choice.

“The scale of decline was steeper than we expected,” Andrew Huber, the district’s executive director for enrollment and campus planning, has said.

EL-19 requires the superintendent to regularly review enrollment boundaries and enrollment zones, tying those reviews to U.S. census data. The policy outlines expectations for managing enrollment, facilities and long-term planning.

The policy calls for new school boundaries and enrollment zones that are walkable and do not further socioeconomically “segregate” schools.

While the policy calls for regular review of boundaries and zones tied to demographic changes, the board itself is responsible for approving any boundary adjustments.

Broadly speaking, school districts typically consider school boundaries in response to increases or decreases in student enrollment; to address overcrowding or underutilization; or when opening or closing schools.

The district hasn’t done this.

The board of education has closed schools based largely on campus size and utilization without comprehensively revisiting attendance boundaries.

The last time the district conducted a boundary study, Richard Nixon was president. That was 1973.

Over time, Denver has increasingly relied on school choice, rather than on neighborhood assignment, allowing families to enroll students outside their attendance boundaries.

That system has given families flexibility, but some said it has also complicated efforts to align enrollment, staffing and facilities, as student counts decline unevenly across the city.

The official enrollment count on Oct. 1 each year is used to determine per-pupil funding.

District leaders have noted that the annual count not only drives state dollars but also shapes staffing, programming and long-term facility planning. Even small shifts can ripple through classrooms and budgets.

Because many school costs are fixed — including staffing minimums, building operations and transportation — enrollment declines can drive up per-student costs at underutilized campuses, putting additional pressure on the district’s general fund.

The district’s enrollment in September stood at 84,113 — a 1.4% decrease from the previous year.

That figure does not include Early Childhood Education (ECE), offered to children as young as 3 years of age. The district had 5,179 ECE students, up slightly from 5,135 the previous year. While ECE students are funded by classroom rather than by pupil, they eventually enroll in district schools.

Including ECE, the district’s total enrollment is 89,292.

During the school closure process, district officials said ECE students were excluded because not every campus offers early childhood education. Good said the ECE numbers have been excluded from the district’s overall enrollment count because the funding is based on classroom, not attendance.

Enrollment is critical in Colorado, where dollars follow students.

Lower birth rates, rising housing costs and gentrification have been cited as key drivers of the district’s enrollment declines.

District enrollment peaked in 2019 with 86,949 students.

The headcount declined each year afterward — until two years ago, when Denver experienced an influx of immigrants from South and Central America whose families arrived in Colorado after illegally crossing the U.S. southern border.

In prior school years, the district enrolled roughly 1,500 of the students. That number fell sharply this year to about 400.

Those shifts highlight how volatile enrollment has become.