Fiscal Rockies: Small businesses drive the rural Colorado economy — but barriers keep growing

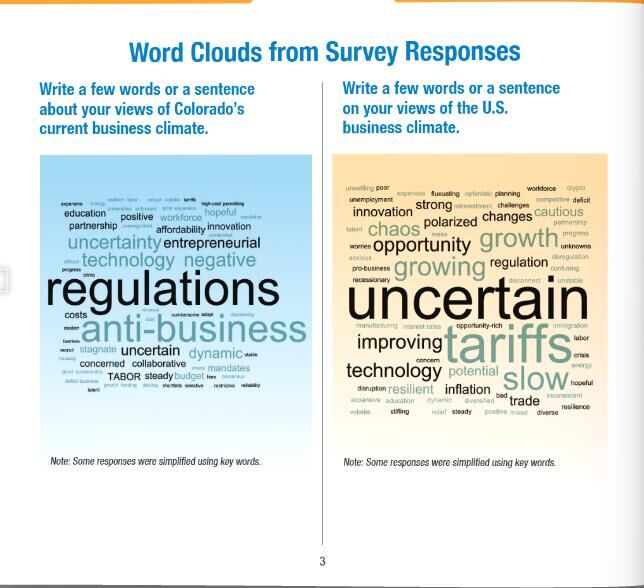

| Editor’s Note: Once among the nation’s fastest-growing economies, Colorado today confronts mounting challenges that threaten its momentum. This series reveals how a state once defined by prosperity is navigating economic cliffs and ridges. We explore the impact of increased regulations, tariffs, shifting tax policies, the high cost of living and widening urban–rural divides have on businesses, workers, and communities. The series also highlights the push to leverage Colorado’s outdoor economy — one of its most valuable assets — for renewed growth, while working to attract industries like quantum and aerospace while capitalizing on unique industries that call Colorado home. |

In rural Colorado, entrepreneurship isn’t just an economic driver—it’s often a necessity. Faced with limited job opportunities, many residents have turned to creating their own livelihoods, fueling local economies and shaping the future of their communities despite mounting challenges.

According to research from the Center on Rural Innovation, rural residents nationwide are more likely to start businesses and tend to earn higher wages than their peers, making them a powerful force in economic development. In Colorado, that entrepreneurial spirit is powerful: nearly half the workforce in rural areas is employed by startups or small businesses.

Colorado State University economist Stephen Weiler said the more rural a county is, the higher its entrepreneurship rate.

“In rural areas by and large, if you want a job, you have to create your own,” Weiler said.

Obstacles accessing capital

While rural entrepreneurs are known for their resilience and adaptability, they face steep barriers to growth. Limited access to capital, shrinking local workforces, and a lack of venture investment make scaling a business far more difficult than in urban centers. The number of rural community banks has dropped by nearly half since the mid-1980s, leaving fewer financing options—and those that remain tend to be more risk-averse.

Sonia Gutierrez started Sierra Concrete with her two brothers, Sergio and Jose, in 2019. The siblings had one employee, one truck and no equipment. Six years later, Sierra Concrete employed 22 people and had completed projects across Colorado and Utah.

While Sierra Concrete has grown, Gutierrez said that living in a rural area and being part of the construction industry make it difficult for her business to access capital.

“Construction in Colorado is seasonal; the beginning and the end of the year are our weaker times,” Gutierrez said. “Banks want to see different revenue sources, and while we might get a big contract, it’s only with one general contractor.”

This difficulty in accessing capital makes it hard for businesses like Sierra Concrete to reach their full potential. The strict regulations that traditional lenders impose, Gutierrez feels, do not support the vast variety of companies in Colorado.

“One solution would be for banks to look at categorizing funding that they’re putting toward construction,” Gutierrez said. “They could be flexible with their revenue, putting it into different sectors.”

In addition, though, to perennial issues of working in a rural area, tariffs have hit the sector hard. Gutierrez said that at the beginning of 2025, prices for lumber and rebar skyrocketed from one day to the next.

“Our bidding prices will have to be elevated,” Gutierrez said. “At some point, it will be difficult to be competitive and get those contracts. That could potentially mean reducing our profit margin, just breaking even, so that we can keep our workers employed so they can provide for their families.”

An organization that is bridging the gap for small businesses in Western Colorado is The Business Incubator Center, led by CEO Dalida Sassoon Bollig.

“The BIC is where you go to keep your dream alive,” Gutierrez said. “It bridges the divide for small businesses. It offers nontraditional access to capital, certifications, credits, and a wealth of information from professional advisors.”

Organizations like The Business Incubator Center are key to the long-term success of rural economies.

“Rural entrepreneurs experience unique challenges and opportunities,” said Jeff Kraft, the deputy director of the Colorado Office of Economic Development and the director of Business Funding Incentives. “We work closely with rural businesses and economic development partners to develop effective programming. Our most impactful programs, which help businesses achieve goals like creating new jobs and accessing capital, have grown out of this type of collaboration.”

Outside forces wreak havoc

Tim Fry, owner of Mountain Racing Products, a Grand Junction-based manufacturer of high-end mountain bike suspension, drivetrain products, and components, says the COVID-19 pandemic and the imposition of tariffs have wreaked havoc on the bike industry.

COVID-19 was a boon for the outdoor industry. Companies worked flat out to produce enough parts to meet the demand for bikes. The years from 2020 to 2023 showed tremendous growth, and some bike companies increased their inventory by 50%.

Fry increased MRP inventory by a conservative 15%. The inevitable downturn came at the end of 2023.

“As a company, we knew the inventory would correct itself,” Fry said. “What we didn’t expect was the second whammy of tariffs and duties and then the third—chaos.”

Fry said he wasn’t opposed to surgical tariffs to address specific problems, such as China’s use of currency intervention to keep the currency undervalued and gain an unfair competitive advantage in international trade.

At a September roundtable event with U.S. Sen. John Hickenlooper, Fry said that before 2025, he did not spend any of his workday on tariffs. Now, he estimates 15% of his workday is dedicated to dealing with tariff-related issues.

On Oct. 7, the U.S. Commerce Department published two requests to add bicycles, frames, and e-bikes to its aluminum and steel tariffs. If the requests are granted, bicycles and frames imported to the U.S. would be subject to a 50% tariff on their steel and aluminum content.

Fry has already started tracking down suppliers and figuring out just how much steel and aluminum is in each piece MRP manufactures, but noted that it is a laborious and time-consuming process.

“It’s another thing added to the bucket of uncertainty which is driving down revenue,” Fry said. “We’re also being much more strategic in our prototyping and testing of new products. It’s less of a ‘let’s see if it works’ and more is it a straight line to market.”

A less business-friendly state

Fry also noted the challenges of operating a manufacturing plant in a rural area, including limited resources, a shortage of skilled employees such as machinists and welders, and a 22% increase in healthcare costs.

“Being a small manufacturer on the Western Slope is a challenge,” Fry said. “I’m always jealous when I’m in Taiwan and the resources in that hub, the talent. If I have a machine that breaks or needs repairing, it’s going to cost me at least a thousand dollars just to get the guy to Grand Junction.”

The challenges of being a small business go beyond international trade disagreements. Fry argued that Colorado had become less business-friendly in recent years, a trend that’s hit rural areas harder. The commercial real estate tax and the personal property tax, Fry said, are “incredibly challenging.”

“Mesa County one year was going to waive the tax for businesses, but only on a $1 million piece of equipment,” Fry said. “That’s not good for small businesses because they can’t afford to buy a $1 million piece. We bought a $400k piece, but that was a huge stretch for us. We appreciate the thought, but the execution missed the mark.”

Read more from the Fiscal Rockies series: