Federal judge lifts public access restriction on Children’s Hospital Colorado’s challenge to DOJ subpoena

A federal judge ordered last month that the public be able to access the filings in Children’s Hospital Colorado’s legal challenge to a U.S. Department of Justice subpoena seeking a broad range of documents about patients, employees and communications.

Children’s Colorado sought to keep its case shielded from public view, arguing that disclosing the details of the Justice Department’s request would traumatize patients and providers who work with puberty blockers and hormone treatments — the subject of the government’s request for documents.

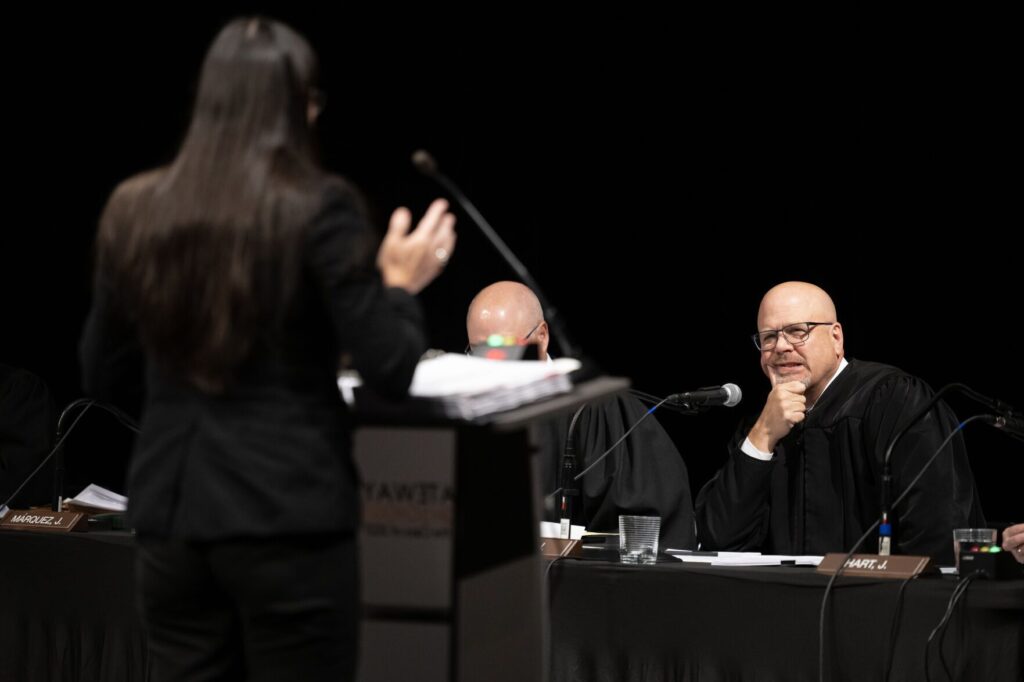

But in a Nov. 17 order, U.S. Magistrate Judge Cyrus Y. Chung noted the subpoena’s existence and the nature of services Children’s Colorado provides were already matters of public record.

“To be sure, the petitioner demonstrates fear and anxiety over the subpoena at the heart of this case. It also points out violence and threats that have historically targeted hospitals providing gender-affirming care,” he wrote. “But it does not show how adjudicating this case publicly, rather than under restriction, threatens additional, concrete harm so as to overcome the strong presumption of public access to judicial records.”

Over the summer, the Justice Department served a subpoena on Children’s Colorado and other hospital systems. The government requested documents, from January 2020 onward, that identify patients, reveal personnel files and disclose communications with the pharmaceutical industry.

The demand was aimed at treatment involving puberty blockers and hormone therapy for children. The Justice Department was focused on gender-related care, which it defined as “any medical, surgical, psychological, or social treatment provided to individuals to alter their physical appearance or social presentation to resemble characteristics typically associated with the opposite biological sex.”

The investigation was rooted in multiple executive orders President Donald Trump issued, decrying “efforts to eradicate the biological reality of sex” and seeking to “rigorously enforce all laws” to deter certain treatment for children seeking to delay puberty or identify with a gender that does not correlate to their sex at birth. A federal judge in Maryland subsequently blocked the portions of the orders withholding related grant funding.

Children’s Colorado quickly sought to quash the subpoena. It argued the request amounted to a “fishing expedition” designed to intimidate patients and providers for conduct that was not illegal under federal or state law.

“In meet and confer calls, the DOJ attorneys handling this matter acknowledged that they have no reason to suspect any form of wrongdoing by Children’s Hospital, or any evidence of misconduct by Children’s Hospital or anyone connected with it,” wrote the organization’s lawyers.

At the same time, Children’s Colorado sought to shield the case from public view, arguing that the subpoena’s existence was already dissuading patients from seeking treatment.

“Several hospitals have attracted protesters with violent messages, including messages conveying that providers who administer gender-affirming care are harming children,” attorneys for Children’s Colorado wrote. “Disclosure of the Subpoena and these proceedings would likely exacerbate such harassment.”

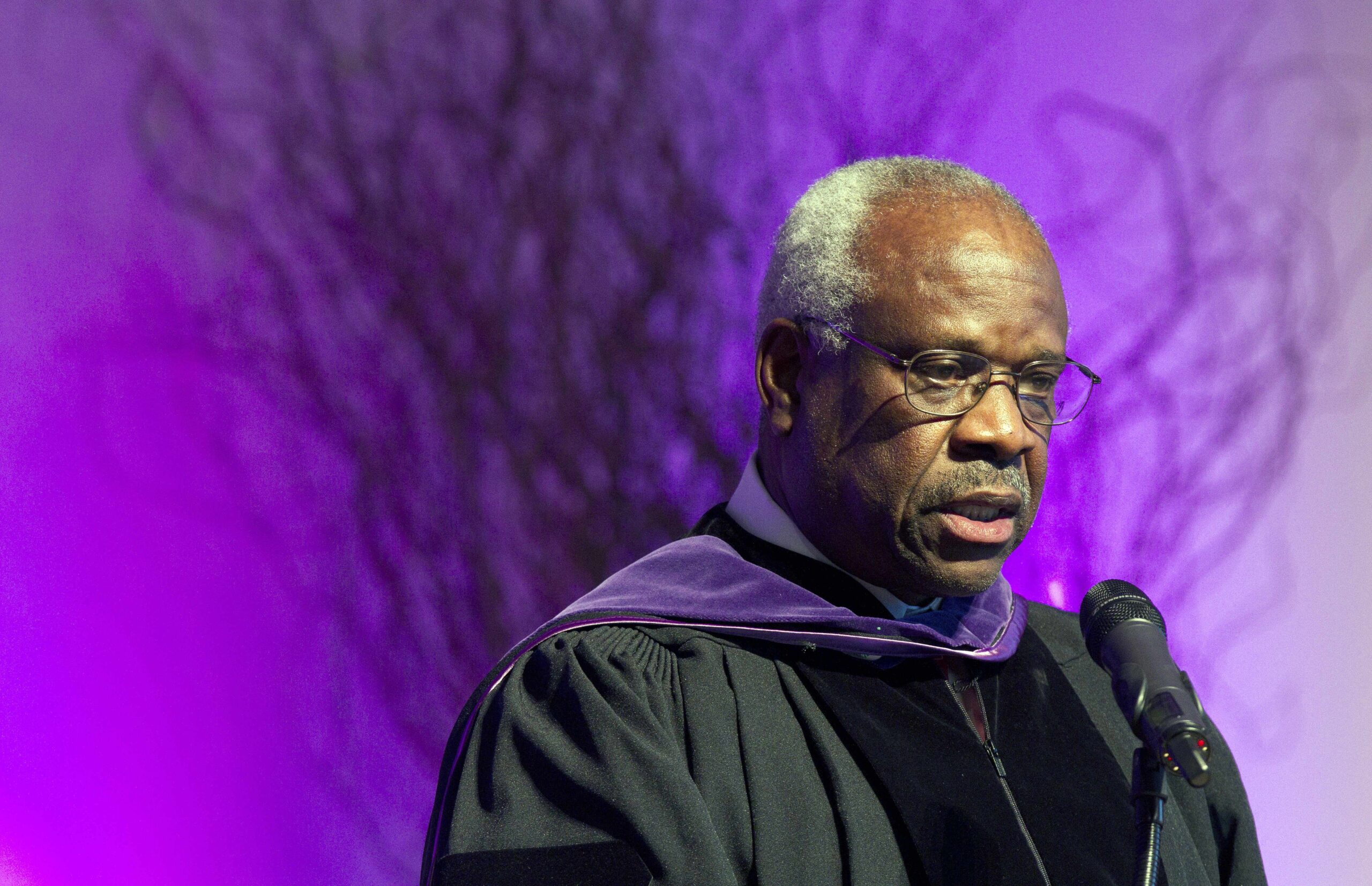

The Justice Department responded that it was investigating whether “persons in Colorado committed federal health care offenses” while providing care to children. The government repeatedly referenced a concurring opinion from the U.S. Supreme Court’s June decision in United States v. Skrmetti, where the Republican-appointed majority held that states may block certain gender-related treatments for children without violating the U.S. Constitution.

Justice Clarence Thomas, writing separately, raised doubts about the drugs involved. The Justice Department, in responding to Children’s Colorado’s motion, likewise referenced “potential consumer-protection violations” that may “deserve exploration.”

As for Children’s Colorado’s request to restrict public access to the case, “It is true that an individual’s private health information is routinely protected from public disclosure in litigation,” wrote the department. “But what CHC argues is that because the United States is seeking information related to CHC’s provision of medical interventions to minors, the very existence of its challenge must be kept secret. This argument stretches too far.”

In his order, Chung wrote that it would be appropriate to restrict individual filings containing patient or personnel information. However, the existing filings did not fall into that category. Chung also found it unclear how releasing details of the Justice Department’s request would spawn further negative consequences.

“After all, the subpoena’s existence is no secret: the petitioner notified its patients and personnel of the subpoena,” he wrote.

U.S. District Court Judge S. Kato Crews is separately evaluating Children’s Colorado’s motion to invalidate the subpoena. He has not yet ruled. A federal judge in Massachusetts quashed a similar subpoena in September against Boston Children’s Hospital.

Children’s Colorado did not immediately respond to a question from Colorado Politics about what consequences, if any, have arisen from Chung’s decision to remove the access restrictions on the case.

The case is In Re: Department of Justice Administrative Subpoena No. 25-1431-030.