Veteran suicide declines after years of focused prevention in El Paso County

Editor’s note: Those who are in crisis or facing suicidal thoughts are encouraged to call the 988 crisis hotline.

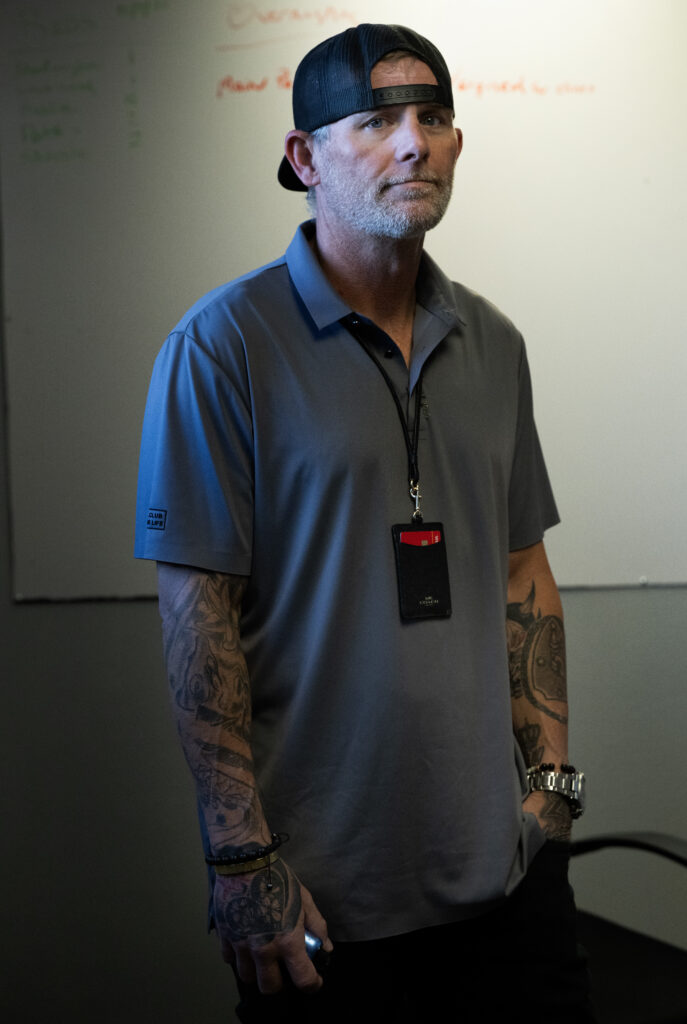

Former Marine Corps Sgt. Heath Miller was facing prison for theft when he decided to get clean.

Like many others, his introduction to opioids started with a prescription. He received oxycodone while in the Marines to treat an injury. When he used fentanyl for the first time, he couldn’t tell the difference, and for a long time, drugs were not a driving force in his life.

But during a troubled marriage, he started leaning on fentanyl to numb depression.

“I would have rather not woken up in the morning,” he said. “I just felt trapped in a situation.”

The long-simmering fentanyl addiction led him to steal packages from his employer, UPS.

Even after he got caught in 2021, he wasn’t immediately ready for help to address underlying issues. It took months in jail and the prospect of losing years of freedom.

“That was enough to wake the hell up,” Miller said.

A lawyer helped him qualify for Veterans Trauma Court through the 4th Judicial District and he got connected to Next Chapter through the specialty court. Next Chapter, a program run through UCHealth and Mt. Carmel Veterans Services Center, started as a state-funded pilot aimed at preventing veterans’ suicide.

The Next Chapter staff supported him through the justice process, he said.

“They became our go-to people to call if we needed anything,” he said.

Through Veterans Trauma Court he qualified for probation rather than prison and entered drug rehabilitation through UCHealth’s Center for Dependency, Addiction and Rehabilitation. From there, he went on to a sober living program.

Tackling veterans’ crisis

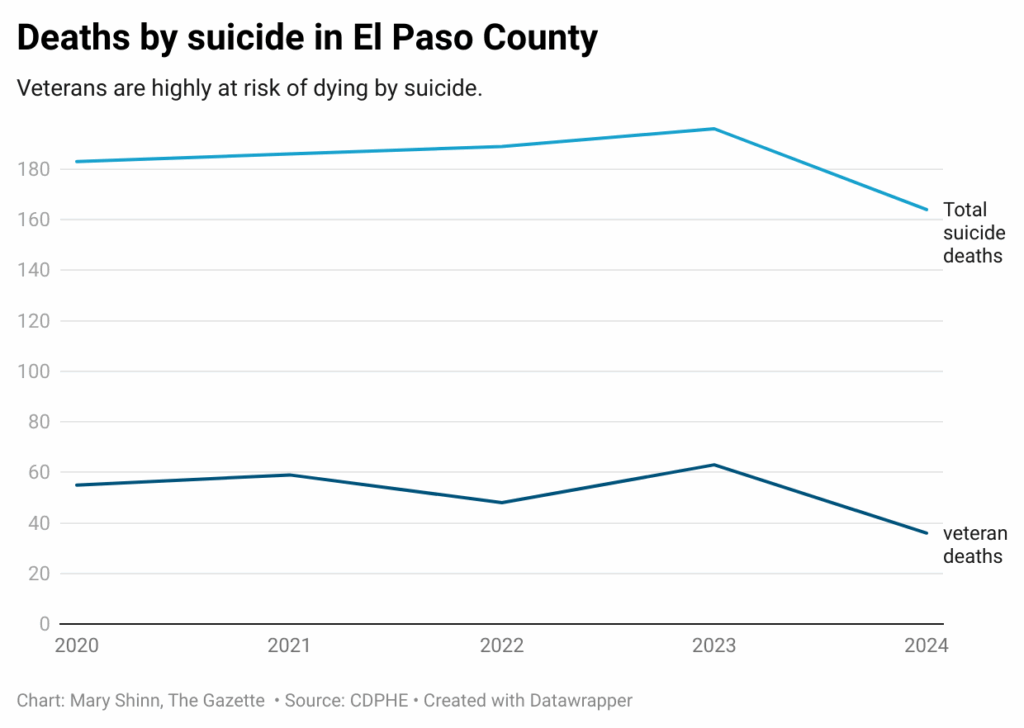

Next Chapter launched in June 2022 to help address the high rate of veterans’ suicide in the state and focused much of its efforts in El Paso County. From 2014 to 2024, 534 veterans have died by suicide in the county, state public health data shows.

The recent efforts to reach veterans through Next Chapter likely contributed to the recent fall in veteran suicide, explained Next Chapter Program Director Damian McCabe. It was a dip that coincided with a decrease in suicide deaths generally.

Despite the strong results, the state did not continue to fund the program because of a major budget shortfall this year. Next Chapter is now working on securing additional funding and recently received a grant through the local opioid abatement council.

Next Chapter’s work has focused on taking on the top three triggers of mental health crisis, finances, relationships and the criminal justice system, said McCabe, not mental illness.

While in the military, troops have built-in camaraderie and without that, some isolate and spiral into crisis, said McCabe, who is also the director of behavioral health and military affairs at UCHealth.

“You’re agitated because your depression and anxiety are with you every day, and nobody knows,” McCabe said, describing the typical pattern. “So you get short-tempered with people, or you choose to self-medicate through drugs or alcohol.”

Once a veteran starts self-medicating, they need behavioral health care to treat their symptoms and help them cope, he said.

Next Chapter provided tens of thousands of behavioral health appointments at no cost over 30 months between 2022 and early 2025, according to a letter on its website. It also brought together numerous partner agencies to help set the conditions for the recent drop in veteran suicides, McCabe said. Those conditions included raising awareness about suicide and immediately connecting those in need with another veteran.

“We believe veterans learned that there were trustworthy, effective veteran-specific services available,” McCabe said

In addition to the fall in veterans’ suicides from 63 in 2023 and 36 in 2024, the total number of deaths in El Paso County fell from 196 in 2023 to 164 in 2025, a drop of 16% state public health data show.

The overall drop in death by suicide follows more than 10 years of community efforts to address the issue, including a focus on youth suicide prevention that started in 2015, said Brittany Riffle, the youth suicide prevention planner for El Paso County Public Health. Nationally, in 2022, the 988 mental health crisis hotline was also launched to help prevent suicide.

“We’ve just seen greater momentum in suicide prevention,” Riffle said. But it’s key the work continues through a decline in the number of the deaths, she said.

In a more normal budget year, the state would have likely extended Next Chapter’s funding.

But the program has needed to look elsewhere for funds amid the state’s $1 billion budget shortfall caused by the federal tax overhaul and cuts to Medicaid.

The funding for behavioral health care through Next Chapter ran out in March. From June 2022 through 2025, the program reached 1,232 people, and 86% of them needed behavioral healthcare, according to the nonprofit’s annual report.

“It’s not just a small gap in funding,” McCabe said.

In September, the Region 16 Abatement Council approved $1.5 million annually for Next Chapter for up to three years to work with veterans and their family members who are dealing with the results of the opioid epidemic in El Paso and Teller counties, McCabe said. The grant agreement was still in process in mid-October, a statement from El Paso County said.

It is also possible Next Chapter could receive funding from a new tax on the sale of firearms and ammunition approved in 2025. The first $30 million in tax revenue will be set aside for victims of crimes and the next $5 million will be allocated to veterans behavioral health. It’s money that will be insulated from any changes at the federal level, McCabe said. But given the current economic environment though the sales tax revenues may not reach $35 million for several years, he said.

During the funding gap, Next Chapter is helping veterans understand their insurance and what benefits they may qualify for through agencies such as the Department of Veterans Affairs. Not all veterans qualify for VA benefits.

Those who come to a UCHealth emergency room for care, are of course seen, McCabe said. Those with insurance can be seen at Mt. Carmel’s vet center.

While the VA is an option for some veterans, they can face a long wait to get into mental health care, sometimes between three to four months, McCabe explained. In that time, if the person is in Veterans Trauma Court, they may get into trouble again while waiting to get into mental health care.

In the long term, McCabe would like to see Next Chapter services available across a broad geographic region of the state through virtual appointments.

In the coming months, UCHeath expects to refer veterans in crisis coming through their hospital emergency departments to Next Chapter so they know that’s an option for care, McCabe said.

A new life in sober living

While living in a Rocky Mountain Sober Living home, Miller found he was good at helping new arrivals and ended up becoming a peer coach.

“I realize that I am someone that people come to talk to because I have been through it,” he said.

When he moved into sober living, he had lost his house, custody of his kids, and marriage in the space of two years.

Since then, he has rebuilt his life, met someone he expects to marry, regained custody of his son and started a career in sober living.

It’s a story that shows: “You can do the work and have a good life again,” Miller said.

He is now the director of housing for Purple Mountain Recovery, the company that purchased Rocky Mountain Sober Living.

Miller runs 12 homes that house nine to 14 people and he sees sober living as a critical piece to successfully breaking the cycle of addiction.

Rehabilitation can teach tools and skills, but if people go back home to the same environment, they are unlikely to succeed. Sober living provides needed accountability, Miller said.

While it is a work heavy with tragic stories, Miller is among those committed to picking up the phone while others are in crisis, and staying with them until they can get the right help.

He said he hopes his story as a combat infantry Marine who deployed to Kosovo and Iraq can inspire others to ask when they need help.

“If I can put my pride as a man aside and tell people I need help and express my feelings to people, anybody can do it,” Miller said.